Subterranean Gallery’s Melaney Mitchell prepares to move up and out

While presidential candidates ponder how to “make America great again,” Subterranean Gallery director Melaney Mitchell is asking a different, better question: How do you make an alternative space alternative again?

Subterranean has long counted as alternative, if for no other reason than its location: The six-year-old art space lives in Mitchell’s cramped midtown basement. But its innovative exhibitions — such as a pair that Mitchell curated last year, Michael Rose’s Z-SPEC and Justin Beachler’s Enterface, for which her boyfriend-slash-digital-exhibitions-manager, Kevin Heckart, fashioned a Second Life version of the gallery — increasingly face the mainstream.

“I’ve gotten to the point with Subterranean where I can — it’s like, when you’re driving and you try to drive with your knees,” she tells me. “I’ve gotten to the point where I feel like I could drive Sub with my knees. And when I started, I was totally white-knuckled.”

So Mitchell has figured out a way to renew Sub’s alt spirit while regaining that jolt of uncertainty: absence. After two years directing the gallery, she’s curating one final exhibition before handing over the reins — and the apartment keys — to Jordan Hauser, a senior at the Kansas City Art Institute.

The valedictory show, an immersive installation by artist Amy Kligman, is titled The Glory Days Will Not Last Forever. The title evokes the ephemera of childhood birthday parties and melted cupcake frosting, though it’s hard not to read it as a nostalgic wave at Mitchell and her predecessor, Subterranean founder Ayla Rexroth.

But Mitchell brushes me off before I can get too precious. She’s more than ready to move on up — to an apartment with windows, from which she can chase that white-knuckle feeling. “I want to take what I learned from this alternative space and apply it to some larger-scale exhibitions, take some risks,” she says. “I want to scare myself again.”

Mitchell took over Subterranean in the late summer of 2013, when Rexroth left to pursue an M.F.A. at Hunter College in New York. Mitchell was Rexroth’s intern at the time.

Well, sort of.

“The Art Institute did not want that to be my internship,” Mitchell admits. It was part skepticism for a still-young institution, part something more practical: Rexroth was putting on a lecture series called The Hot Tub Dialogues at the time, and KCAI’s powers-that-be questioned the, uh, safety of the endeavor.

“They thought I would die,” Mitchell says, sounding serious. “Basically, like, ‘You’re going to slip and fall and die if there’s a hot tub on concrete floors in a shady basement somewhere.'”

Instead, her then-instructor Jordan Stempleman advised her to spin the internship into an art-writing independent study. She still performed some typical duties — she built two walls during her first month of work — but she also wrote up The Hot Tub Dialogues for Subterranean’s nascent blog, detailing the rotating casts of performers, chefs and bartenders.

“It was a high-class party,” Mitchell says, a little wistfulness in her voice. “And it was an interesting way for me to navigate getting to know all of these artists in Kansas City in a really intimate setting where they were, you know, a little bit toasted. It was stuff like that that really made me fall in love with the space.”

She’s not alone. Hang around Art Institute grads for long, and you’re bound to hear a few stories about their sauced but scholarly escapades below ground, in this place that holds maybe 30 friends or 10 strangers. (Forget the fire code: When you visit an off-the-grid basement gallery in a rental apartment, you’re entering a tacit agreement to abandon both pretense and propriety.) When shows were busy, they felt cramped, the art perilously close to an errant drunk’s elbow. But at the right density, they were about as personal an experience as you can have with art — and artists — in this town.

[page]

“The thing I always loved about Sub was that the low ceilings forced you to talk to one another,” Mitchell says. “There were always unintentional conversations with people in the arts community. When I was helping Ayla, I would always end up talking to people that I had never imagined having conversations with. I don’t know what it is about having the ceiling right here and the work right there, but the proximity forces you to really look at stuff. And be enveloped by it.”

The space has often forced other, less pleasant effects.

“The gallery started out as this raw, nasty storage space in the basement of an apartment building,” Mitchell says. She drops the name of her property management company like a curse word, then hastily backtracks: “Don’t publish that.”

I press her a little. After six years of operations and some 15 public exhibitions, can her landlord really not know?

She shrugs. “It’s extremely under the radar. Jordan’s moving in, and I’m just giving her the keys. My landlord did see the space once when Ayla moved out and was just like, ‘Oh.’ And then he raised the rent on me by $50.”

To hear Mitchell tell it, that extra money yielded no extra benefits or repairs. During her two years in the apartment, Mitchell has had to solve plenty of problems for herself. When it rained, Sub flooded. When an upstairs apartment’s bathtub overflowed, Sub flooded. The day of an opening — Ryan Shrum’s HOME // SPACE — the gas company showed up at the same time as a class of KCAI students. A gas leak on the third floor was threatening an evacuation. They wanted to boot everyone out and padlock the door.

More recently, the air conditioning died just ahead of last summer’s slate of planned programming. Heckart rigged a unit with some ice, a fan and a modified plastic bucket. Mitchell shows me the contraption, all protruding PVC pipe and jagged edges. It looks like the kind of device that could get you on a terror watch list. Most curators don’t have to do this kind of thing.

When Mitchell moved in, she painted the floors with Titanium White pigment. She then discovered that, unless Titanium White is exposed to sunlight, it yellows within six months. When the floors start to look like an antique wedding dress, she knows it’s time to repaint.

Given these events, I can’t help but wonder if her departure is more about the frustrations of the space than it is about the pursuit of new adventures.

“I’m more about being out of the windowless tiny apartment,” Mitchell tells me. “Yeah. Subterranean is strange. … It’s really, really temperamental, and it changes on a dime. You’re living in the belly of a building, as Ayla always put it, and that makes things weird.”

Compounding troubles is that the belly is accessible only by a parking lot up a private drive — there’s no street-facing entrance. First-time visitors can have a hard time finding the gallery, if they find it at all.

“That’s the other thing I kind of want to get away from,” Mitchell says. “Because if I’m doing things that are engaged with the public a little more heavily, it needs to be a little less off the grid.”

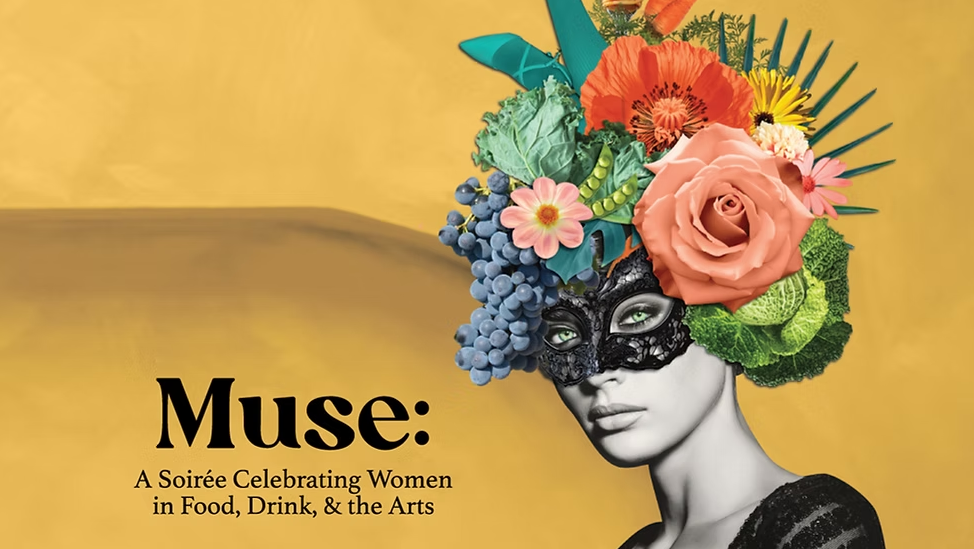

I ask if she’ll still be able to scratch that curatorial itch once she leaves. She tells me about a show she’s curating at La Esquina (with friend and fellow writer Blair Schulman), but her focus seems elsewhere.

[page]

“I feel like my curatorial itch is being overtaken by a studio rash,” she says. “I really need to go make stuff for a while. And work on writing.”

When she’s not curating at Sub, Mitchell writes and edits for Informality, an arts and culture blog she started along with Subterranean heir Hauser. And last year, she was awarded a yearlong art-writing and curatorial fellowship at the Oklahoma Visual Arts Coalition. The fellowship was equal parts brutal and beneficial. She mentions one highlight: a meeting with Chloë Bass, writer at the acclaimed art blog Hyperallergic.

“She took one look at my piece and was like, ‘Well. This is a press release. This is not a review.'”

Ouch.

“Yeah. And I thought, OK. But this is what Kansas City’s used to. So let’s do it. Let’s shake things up a bit.”

A couple of days after our first conversation, I meet Mitchell again to check on the exhibition’s progress. She is sitting cross-legged on the gallery floor, going through her boyfriend’s record collection as she takes a break to talk to me. Bits of colorful balloon are stuck to the knees of her wet-look leggings, and every few seconds comes the percussive rap of a staple penetrating drywall. Kligman is hammering deflated, tubular balloons — balloon-animal balloons — into pompom clumps. The installation — one of the artist’s largest yet — sprawls floor-to-ceiling across walls and load-bearing poles. The goal, Mitchell says, is to make the experience overwhelming.

On the early January day I visit, it’s the process that feels overwhelming. Mitchell is splitting her time between packing up her belongings and joining Kligman to staple flowers and crepe paper to Subterranean’s walls. Luckily, she has help: Mitchell has two interns, KCAI-approved.

With a couple of more days to go before the work is complete, Subterranean already looks like a group birthday party for the Charlie and the Chocolate Factory brats. The walls are coated in drink umbrellas, streamers, clusters of tinsel. Paper fans jut out from a corner like stiff petticoats. Behind it all, a deliriously decadent backdrop — wallpaper Kligman, a former giftwrap designer and Hallmark employee (“I spent a year in ‘Party,’ ” she says), designed herself.

Kligman takes a step back, appraises the wall, and turns to a box of tiny glow-in-the-dark spiders, ignoring the piles of boas and leis on the floor. “I’ve learned this process is sort of like watercolor,” she says, assembling spiders into pairs. “You’ve got to be careful about what you put down first. Because when you build it up too much, it’s hard to undo.”

The gallery starts to swell around me, arterial walls clogged with pink, and I can’t help but think of a school-wide art project from my elementary days. We blanketed a hallway with thickets of construction paper trees and dense hanging vines to bring awareness to the destruction of the rainforest — irony being something you unlock in retrospect.

Mitchell must be feeling something, too, because she starts telling Kligman a story about having been at Walt Disney World on September 11, 2001. It soured the experience, to say the least.

“That’s kind of what this exhibition is about, in a way,” Kligman says. “Like, it’s supposed to be this magical time, and then: What is happening?”

Mitchell’s magical time is counting down. Sub will close later this month, following Kligman’s exhibition. And so far, there’s no reopening date on the calendar. Her successor, Hauser, is still gathering ideas from collaborators, making plans. She tells me not to expect any programming until summer.

[page]

Mitchell was in the space six months before she opened her first exhibition. This kind of thing can’t be rushed. But the next iteration of Sub seems likely to continue some of the conversations Mitchell started. Hauser’s interests align with how digital art and Internet art have evolved in the past five years. Ditto the relationship between social issues and social media.

“That’s what I’ve been thinking about a lot lately,” Hauser says. “And I’ve been considering, with Sub, if I should make that a focus or not.”

She goes on, with a ready laugh: “This is completely new to me. I’m pretty confident I won’t — in any way — get too comfortable too soon.”

Hauser’s attitude feels right for a gallery that’s always toed the line between alternative edge and institutional polish, whose very existence has hinged on a tightrope act of perilous particulars: a curator who doesn’t mind living in a windowless and flood-prone apartment, a public that doesn’t mind knocking on a few wrong doors to find it, a landlord who doesn’t ask questions and never stops by.

Nobody’s glory days last forever. But with a little luck — and a lot of Titanium White — Subterranean’s might last a little longer. •