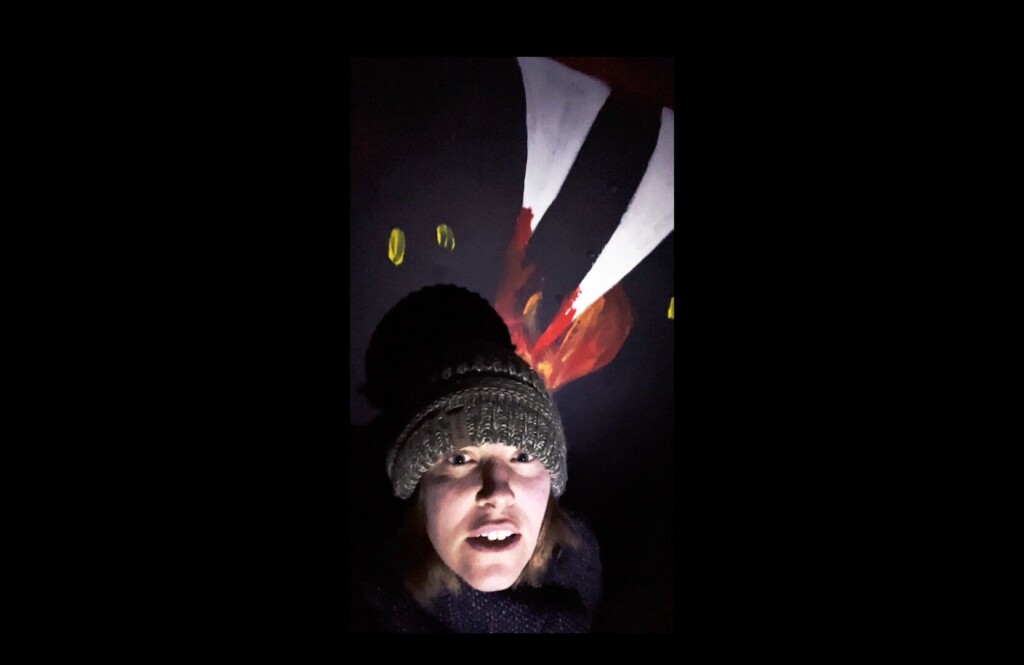

It Doesn’t Get Any Better Than This: Missouri filmmakers blur the lines between reality and fantasy in first feature-length horror film

Rachel Kempf and Nick Toti moved to Kirksville, MO from LA in the wake of COVID, with a dream of continuing to pursue their film careers in the Midwest.

They’ve already published a series of horror movie anthology-style books under DieDieBooks, and now they’ve just finished their first feature-length film as DieDieVideo, It Doesn’t Get Any Better Than This.

Kempf and Toti bought an abandoned duplex in Kirksville for a low price with the intention of cleaning it up to film a horror movie. Rather than refurbish, they began to craft a narrative about what kind of terror might bless their mess.

An idea began to take shape, and The Kempf-Totis took centerstage, as their low-budget feature became a found footage fright fest wherein the couple became fictionalized versions of themselves—including the process of purchasing a duplex to film a found footage horror film.

“We really tried to make it seem [believable], and part of that extended into,” says Toti. “We had to make character versions of ourselves that were, we just made ourselves kind of dumber than we actually are. But just kind of the most manic, reckless versions of ourselves were what we played up for the movie, but it’s not that different from our actual personalities.”

Pulling from personal footage dating back more than 20 years, the film feels like the product of an entire lifetime, and even loops in the backstory of a friend of theirs—Christian—who becomes another actor/character in the film, also playing a lightly fictionalized version of himself in this meta-meta narrative.

Toti and Kempf’s characters in the movie realize soon after moving in that other people are drawn to the duplex, standing and staring at the house like a deer in headlights, but the people never approach the house. The main characters have the epiphany that they may have a real-life horror story on their hands, and they get to work on making their own found footage film.

The blend of the real footage and the footage created for the movie blurs the lines between reality and fantasy, keeping viewers guessing right up until the end.

“I have a friend who watched it,” says Toti. “And she was texting me while she watched it, and it was probably over halfway through the movie before she realized, ‘Oh, this is fake.’”

In line with making the film as believable as possible, much of the storyline was improvised—being the owners of their movie and equipment, and simultaneously being the two main actors in the movie made room for far more flexibility than a Hollywood production.

Initially, they had planned to base much of the plot on some of Kirksville’s history and spooky stories. One aspect that became part of the film early on was the “cult of staring people,” which was inspired by several anecdotes from their fellow Kirksville residents about witnessing people standing outside and staring into their houses. Ultimately, aside from that, they deviated from their original plan.

“Over time [it] evolved into kind of its own thing,” says Kempf. “I was editing as we were shooting things, just trying to put it into a narrative, and what developed was we would string scenes together once they were edited and be like, ‘What does it need?’”

They spent many hours combing through other found footage films to see what worked about those films in terms of believability, and what didn’t, along with a found footage YouTube series “Marble Hornets.”

“Basically any we found, and the worse, the better—like we tried to find ones that people shot for like $200,” says Toti.

But you won’t be able to find this movie online or on streaming services any time soon—in fact, ever. Kempf and Toti never plan to widely distribute the film, only screening the film in a live setting.

“It’s really nice to watch in a theater with a lot of people because then it’s like they’re all part of it as well—you’re all part of the magic,” says Kempf. “We’ve been trying to tour it around DIY places like an indie band would, and small venues. I feel like when you put it online, you’re trying to get sort of an institutional approval, like the rubber stamp, and it feels more mechanical. But I feel like we shot it in a way that feels alive, and we want to distribute it in a way that, or show it to people in a way that feels alive. I think that’s something that’s sort of missing from a lot of films today.”

Kempf and Toti want their film to feel like an event, rather than the more passive experience of watching a movie at home.

“That was the intention from the beginning,” says Toti. “We said when we started making it, ‘We’re gonna make something that’s very intimate and that really demands an intimate experience for watching it.’ It’s a movie that really will potentially be ruined by people feeling like it’s okay to go on their phone or whatever while they’re watching it. Like the movie needs to cast a spell over you.”

Yet, they aren’t limiting the screenings to festivals, or even specific venues. They have their own projector, screen, and Bluetooth speaker, making it possible to show the film almost anywhere.

“We already screened it in a guy’s—essentially his driveway indicator—and it was an amazing screening thing, and like 20 people showed up,” says Kempf. “Little stuff like that, where there’s some person who wants to make an event happen.”

“We’ll show it in people’s living rooms,” adds Toti. “We’ll show it wherever if we can drive there, basically, and somebody wants to show it, we want to go show it.”

To learn about upcoming screenings of It Doesn’t Get Any Better Than This, sign up for DieDieBook’s mailing list.