Memoir Each One Teach One continues where a 1991 Pitch article left off

In the spring of 1991, activist Ron Casanova started the Kansas City Union of the Homeless.

Of the homeless, not for them, he emphasizes in his memoir: “The language is important.”

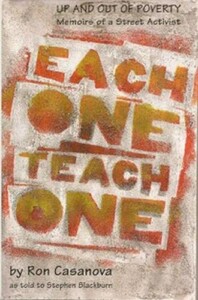

Originally published in 1996, Casanova’s autobiography Each One Teach One is a story of redemption up and out of poverty after growing up mostly houseless in Manhattan. Though he passed on in 2011, his story lives in the pages of the book coauthored by former Pitch writer Stephen Blackburn and in the streets of Manhattan, Philadelphia, and Kansas City, where he helped organize the unhoused community.

With a message more valuable than ever in the midst of the country’s worsening housing crisis, Northwestern University Press reissued it in a paperback this May due to increased demand from independent bookstores and libraries.

During the pandemic, the world’s ten richest men doubled their wealth. In the United States, wealth held by its billionaires increased by 70%, further widening the wealth gap that has exponentially expanded in recent decades.

And while the mega-rich throw millions at their second, third—or ninth—homes, homelessness rates in the U.S. have been climbing by about 6% each year since 2017. From 2019 to 2022, the number of unhoused individuals in Jackson County increased by 193 percent.

While there’s a slew of factors contributing to the housing crisis, Blackburn says it largely boils down to a failure of the government to ensure affordable housing and a livable wage. This critical lens led Blackburn to Casanova when working on a 1991 Pitch article about the difficulties of living on minimum wage.

“I was interested in diving into the issue of minimum wage and how it’s ridiculous to even call it minimum wage,” Blackburn says. “It’s not even the minimum you need to survive.”

In his research, social workers pointed Blackburn to Casanova, who had already significantly impacted organizing the unhoused in Kansas City since he moved there from New York in 1989.

One of the biggest misconceptions about houselessness emphasized by Casanova is that the unhoused do not have jobs. But this claim is easily disproved when a full-time job on the federal minimum wage of $4.25 an hour puts you well below the poverty line in 1991.

For those living on minimum wage trying to make ends meet, the danger of becoming unhoused is much higher than many would expect when you’re forced to choose between food and rent.

“From what I’ve gathered and experienced myself, the minimum wage is a joke,” said Casanova in the 1991 Pitch article.

Flash forward to the present day, and the federal minimum wage has been stalled at $7.25 since 2009, a rate that would put a full-time minimum wage employee $11,000 below the poverty line in 2019. That’s accounting for working 40 hours a week and 52 weeks a year.

Factor in inflation and the link between stagnant minimum wage and soaring homeless populations is glaringly clear—1991’s minimum wage would equate to $9.13 in today’s dollars, about 26% higher percent higher than today’s rate.

In Casanova’s story, readers see a number of other myths busted about houselessness that dehumanize the unhoused and hinder progress in mitigating the crisis.

Some of the big ones: They’re lazy and don’t want to work. All unhoused are drug addicts. Or even that they chose to be homeless.

So long as people adhere to this mindset, they will remain ignorant of the truth. And the truth is that “given opportunity and diligent compassion, underprivileged and impoverished people can and will change themselves for the better,” Casanova said.

He knows this to be true from his lived experience. When he was three years old, Casanova’s mother passed away and he was placed in an orphanage in Staten Island. He never got the support he needed at the orphanage, and in 1953—at just eight years old—he ran away for the first time and faced the streets of New York alone.

A self-proclaimed “Puerto Rican with a black background,” Casanova spent his childhood in and out of foster homes, juvenile detention centers, and youth homes. He got mixed up in gangs, alcohol, and drugs and endured abuse at the Matteawan State Hospital for the criminally insane.

He turned to odd jobs, prostitution, and theft to feed himself and drugs to cope. Sometimes he wouldn’t eat for a long time on purpose, training for times he couldn’t buy or get food.

In the late ’80s, he got his act together. Casanova helped foster the houseless community of Tent City in Tompkins Square Park, organize demonstrations against evictions and for squatter’s rights, and lead a group in the “Housing Now!” march from Boston to Washington, D.C. in October ’89.

From that point on, Casanova committed to a life of activism.

“That moment facing the bullet, I truly recognized and accepted my responsibility as an activist for homeless people,” Casanova says.

In 1989, Casanova moved to Kansas City, where he learned there were no unhoused organizing themselves. He took the reins, founding the Kansas City Union of the Homeless to mobilize the community.

The theory of the Union of the Homeless was that a person has to have a place to start. And for those who have been unhoused for a long period of time, the place to start isn’t a job but rather a stable living environment with privacy, food, clothing, and support.

Spearheaded by Casanova, the Union would acquire three Empowerment Houses. Donated by individuals or the Missouri Housing Development Commission, each house was a place for those without a place.

In exchange for $70 a month and fixing up the deteriorating houses, individuals had a safe place to keep their belongings and art while they worked, went to school, received counseling, and got back on their feet.

As long as residents adhered to the Union’s ideals for the Empowerment Houses—no drugs or alcohol, receiving counseling for addiction and AIDS— they were entrusted to assume cooperative responsibility for the household.

One of the biggest messages pushed by Casanova was that the unhoused need to be the ones to run the shelters, food resources, and other programs rather than continuing to funnel millions into ineffective bureaucracy and the pockets of what he called “poverty pimps.”

To solve the housing crisis, governments and activists would need to work with the unhoused rather than allowing religious organizations to continue telling them what they need.

“Very rarely do people listen to what a homeless person thinks or says,” Casanova says.

Danny Alexander, former Pitch writer, fellow activist, and friend of Casanova’s, says this philosophy is every bit as important today.

“People like Cas were telling us that the band-aid solutions we’d developed so far were not working, and this was not going to go away,” Alexander says. “It’s a message that now seems about 30 years ahead of its time.”

Indeed, the unhoused today are still fighting to have agency in their own lives and fight for survival as bureaucracy continues to fail them.

In the past four years, California has spent $17.5 billion trying to combat homelessness, coming out to a hypothetical $102,941 that could have gone to each unhoused person in the state. In that same time period, homelessness actually grew.

“A big bureaucracy leaks money in places that the money doesn’t need to go,” Blackburn says.

The Kansas City unhoused community is mobilizing against this issue, with organizations like Kansas City Homeless Union laying out demands in 2021 for the city to stop investing millions in shelters, services, and other bandaid solutions.

Echoing the efforts of Casanova, the Union argued these funds should instead be invested in converting vacant and city-owned property into homes for the unhoused.

If nothing else, Casanova’s life story of overcoming a traumatic childhood of homelessness and finding redemption in helping other people makes the story worth the read.

“Everyone was Cas’s brother or sister,” Alexander says. “He signed every dispatch “Through Peace, Love, and Understanding.” He helped me understand so many things in concrete terms that were only abstract ideas before.”

But ideally, Blackburn hopes the book inspires readers to recognize the humanity and dignity of these individuals whom society would rather ignore. To see each of them as a person with a story and a name, and not a leech or inconvenience you encounter on your commute to work

Twenty-seven years after its original publish date, it is a critical time to center the voices of those who are actually unhoused and stop speaking for them—instead of throwing money at the same bureaucratic programs and “poverty pimps” that didn’t work then and aren’t working now.

The housing crisis isn’t knocking on our cities’ doors. The unwanted guest was ushered in a long while ago by governments refusing to ensure a liveable wage and enabling exclusionary and low-density zoning—effectively slashing affordable housing for those pushed into poverty. And as a social collective, we can choose not to accept it.

“I think society is going to have to demand that we not let people fall into the streets the way we’re letting them,” Blackburn says.