The mad science of modern baseball

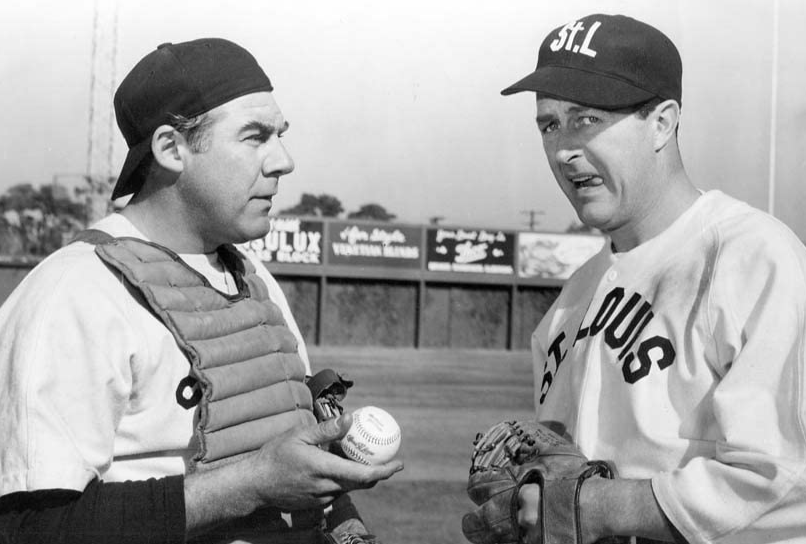

One of my favorite sports movies is It Happens Every Spring (1949) in which a baseball-crazy professor accidentally invents a wood repellent. Naturally, he puts it to good use by adopting an alias (King Kelly) and signs with the Cardinals leading them to the World Series. Spoiler alert: In the climactic final scene, with the repellent supply exhausted, he delivers one last pitch resulting in a screamer back through the box which he snags barehanded. Of course, the injuries are career-ending.

Flash forward to 2021 and the latest “wood repellent” is Spider Tack.

Spider Tack was invented as a grip-enhancing product. We may never know which pitcher discovered its ultra-sticky characteristics, but with it the pitcher can impart 10% more “spin rate” to his pitches which, in turn, changes the aerodynamics of the ball and increases the curvature of the pitch.

I am a former professional pitcher (prior to free agency), certified physics teacher (prior to string theory), and founder of a data analytics company. Essentially, an old-timer trying to keep up but with an enduring love of the game. My wife thinks my enjoyment of a pitcher’s duel is the height of ennui. That said, baseball has a problem—games are too long with too many strikeouts and not enough action.

The Revenge of the Nerds

Modernity has taken over much of our lives. Sports is no different. Technology, advanced analytics, and improved training make baseball a different game than just a few years ago, with many unintended consequences. The three of the most dramatic changes, though, are pitch tracking (spin rates), electronic strike zones (strike zone has changed), and advanced analytics (the Shift).

The spin rate is important for a number of reasons. In the mid-18th century, Daniel Bernoulli asserted that fluids (in this case, air) moving at different speeds around an object (baseball) results in differing pressures on the sides of the object. Higher pressure on one side with lesser pressure on the other results in the ball curving. More spin creates a higher relative speed on one side of the ball compared to the other. All of this creates more curve on the ball.

Before Spider Tack, the greater spin rate was created by the levers of the arm: elbow, wrist, and fingers. More Tommy John surgeries occurred because of more stress on the elbow to create more spin. With Spider Tack, the ball stays on the last lever in the sequence: the fingers. Spinning a baseball is similar to snapping your fingers—the well-timed “snapping” of the wrist and fingers imparts.

This year the average spin rate moved to 2500 RPMs vs the old standard of 2300 RPMs. As a pitcher from a past generation, I’ve been wondering about the increase in strikeouts and pitches in the dirt (pitches that fly less than 60 feet). There are other reasons for more strikeouts. The strike zone has changed along with the emphasis on launch angle. But clearly, the changes in the flight patterns of the pitched baseball are harder on hitters because they don’t resemble pitches they’ve seen in the past—except those from elite hurlers. I theorize that the pitches that are bouncing in the dirt are caused by increased spin rates causing the ball to dive prematurely.

A gadget that measured spin rates giving coaches and players a heretofore unavailable window into physics and a new way of teaching the art of pitching also caused an increase in strikeouts.

Getting the ball to curve more or later or even “fall” slower changes a pitcher’s effectiveness. Even a 95 mph fastball is actually falling unless you impart more spin to keep it on the same plane longer.

Trust me, hitting big-league pitching is an incredibly rare skill. Six-tenths of a second to do anything is difficult, let alone enough time to calculate where a baseball is going to be when you swing at it. Most fans will never hear the angry sound of a baseball traveling 90+ miles per hour near your body. It’s frightful.

The K Zone is the electronically virtually created box on the screen so the fan can judge if the pitch was in the strike zone or not. As umpires are evaluated and judged on their ability to call balls and strikes, I’m convinced that the strike zone is a little bit wider and taller—and taller is making it tough on batters. I believe that is a direct result of K Zone technology that has changed how umpires ump.

Hitters today seek pitches that they can “launch.” To do that, the hitter wants the bat to create some backspin to propel the ball high and far enough to clear the outfield fence. To impart backspin, the batter has to make contact south of the ball’s equator with an upward angle of the bat meeting the ball.

The rules say that the strike zone is technically at the armpits. For years, that pitch was rarely (almost never) called a strike and consequently, batters grooved their swings to swing at pitches waist high or lower. That pitch is much easier to launch than one above the belt. With a taller strike zone, pitchers can work up in the zone knowing that they can avoid the batter’s hot zone and get a called strike. Notice how many more pop-ups and fly balls there are now not to mention the inflated number of strikeouts.

I predict an electronic umpire calling balls and strikes will devastate batting averages.

In 1977, Bill James authored his first Baseball Abstract and it slowly and eventually changed the game. James questioned every assumption that had guided baseball—check out the book or movie Moneyball, which is based on James’ book.

Enter Advanced Analytics, whereby every batted ball is archived allowing coaches to understand every hitter’s tendencies. What naturally followed was the realization that the traditional positioning of the fielders was downright foolish. If a player was likely to hit the ball to the left side of the diamond 75% of the time, why wouldn’t you position the second baseman on that side of the field? The upshot of this was fewer hits.

The issue is that hitters cannot simply hit for the gaping holes in the defense or bunt that direction. It’s hard to do that if you haven’t spent a lifetime practicing those techniques and the pitchers are aiming their pitches to prevent that (pitching inside to induce pulling the ball, for instance).

So what is MLB doing about these issues? First, a crackdown on the sticky fingers. You’re going to see umps checking hats and gloves for Spider Tack or something similar. Spin rates are returning to historic levels, with 10% less, and batting averages are up 10% since the crackdown was announced.

The minor leagues are experimenting with rules to limit the Shift. Ted Williams would’ve loved that rule change since he stubbornly refused to give in to it like many of today’s players.

The minor leagues are also experimenting with electronic umpiring as they instantly feed the ump with the K Zone verdict to “help” the umpire. As I said, it will change the game more radically than the fans anticipate, as pitchers will become very adept at nipping the corners making batting averages even lower.

Despite the incursion of technology, it’s still a great game. The athletes have never been better.

I just wish the games were like my hero Bob Gibson’s. When he pitched, they were always less than two hours.