Omaha’s Stakes: KC pins its violence reduction hopes on an unproven program, leaving us with a familiar pattern of platitudes in place of progress

Over the last 20 years, the 4.16 square miles that make up the Santa Fe neighborhood have been the core of homicides in Kansas City, making up 20.5% of total homicides that have occurred in the metro.

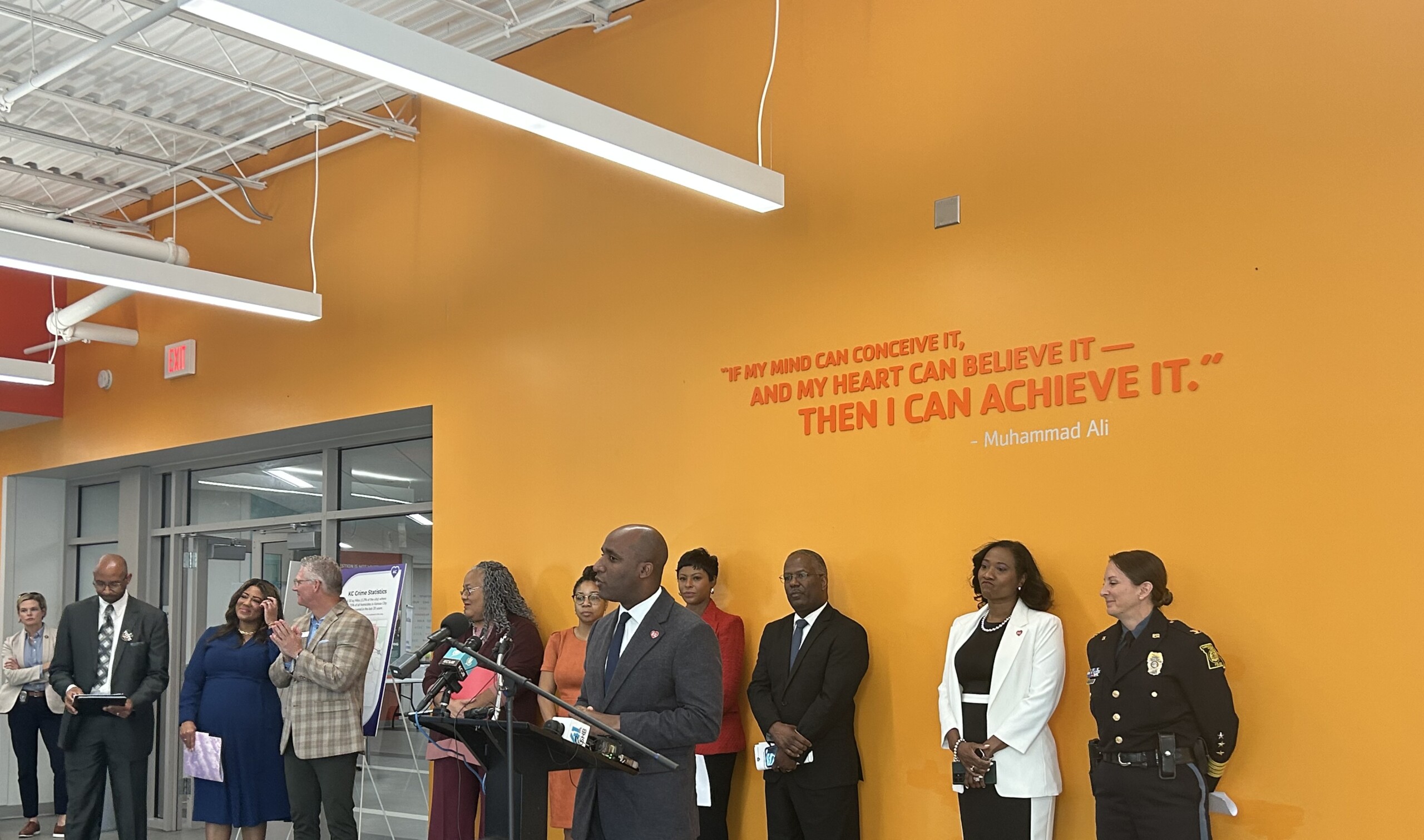

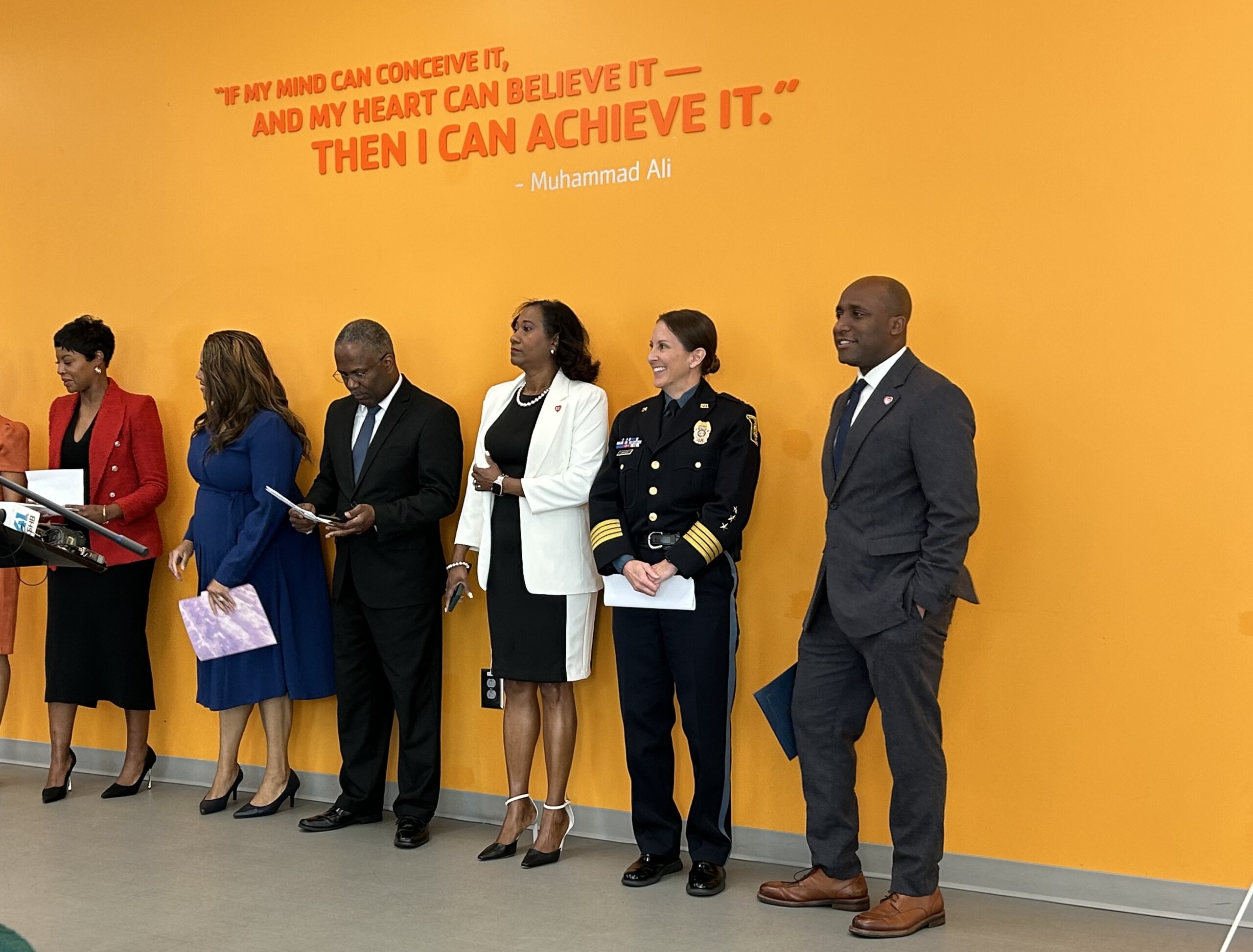

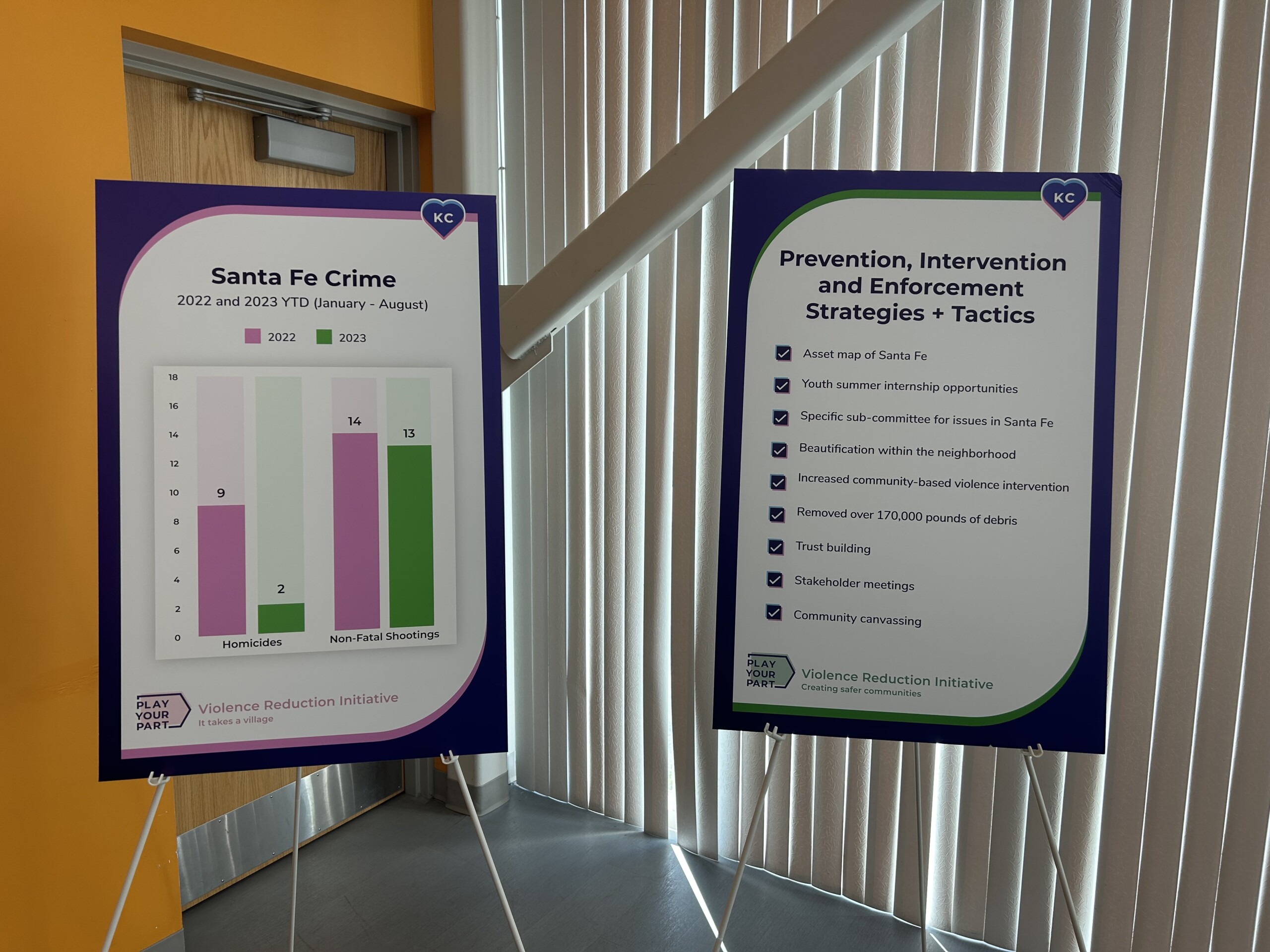

On Tuesday, Oct. 10, KC Common Good hosted a press conference at the Linwood YMCA/James B. Nutter, Sr. Community Center to report on the Joint Violence Reduction Initiative in Kansas City’s Santa Fe neighborhood—a model that they took from Omaha, with statistics provided by KCPD at the press conference claiming overall homicides in the Santa Fe neighborhood have decreased from nine in 2022 to two as of August of this year. Statistics shared also claim non-fatal shootings have decreased from 14 in 2022 to 13 in the same time frame.

While steps in the right direction, these stats are just the first of many that are touted as victories in the war on violence, despite being such a small, nebulous sampling that conclusively connecting this to any kind of actual change feels like a bridge too far.

“In the past decade, the gun death rate amongst children and teens has increased by 87%. Gun violence is currently the leading cause of death for young people in the United States,” CEO of KCCG Klassie Alcine says.

KC Common Good and the KC 360 Program have had $426,890 worth of taxpayer dollars to put towards these endeavors. [Note update at the bottom of the page for more information on these figures.] Funds have gone into different programs such as youth internships, the removal of over 170,000 pounds of debris, construction of speed bumps, property improvements, KCPD data tracking, and more during the past year.

While local leaders are at the forefront of this fight to end violence in the historic East Kansas City neighborhood, they are calling upon the community as a whole to get involved as well.

“For those in the business community watching, we are very proud of the $30 million from the public sector. We want $30 million from the private sector,” Mayor Quinton Lucas says. “For those of us around here in the community who have had the opportunity to engage and volunteer, we ask you to step up and do so and to speak to all who can do it.”

KCPD Chief Stacey Graves also made it clear that these violent crimes affect each and every person within Kansas City limits.

“If a life is taken by violence in Kansas City, everyone should be concerned. Everyone should ask themselves what can they do to reduce violent crime in our city and in our neighborhoods,” Graves says.

Omaha founded its version of a violence reduction system in 2008, reporting that violent crime has dropped 50% in specific neighborhoods since going into effect. Willie Barney, CEO and founder of the Empowerment Network of Omaha, was in attendance at the press conference to give remarks about Omaha’s progress and how that has correlated with how Kansas City is going about the situation.

“You start with one area; you don’t try to take on all of Kansas City. Take one area and show what’s possible,” Barney says. “In Omaha, we started with one village. We now have expanded to 12.”

Other work that KC Common Good has done is providing resources for individuals who refrain from speaking with law enforcement, as well as setting up success plans for individuals who are scheduled to be released from prison within six months.

KC Common Good also engages in the multidisciplinary public safety task force in partnership with KCPD. This means that they find locations where crime is substantial and do an unannounced site visit on the premises to execute an ordinance check.

If their premises violate ordinance policies, they inform the business or residential property owners to update their resources for safety purposes. If they do not comply, the organizations are prepared to prosecute these individuals.

“Pick your poison because everybody has a part to play, even our business owners. You must invest in the safety of your patrons, and the city of Kansas City is requiring and demanding that,” Quinton Lucas’ Director of Public Safety, Melesa Johnson says.

Kc 360 2023 Homicide and Non Fatal Shootings Data in the Santa Fe Neighborhood. // Photo by Joe Ellett

What’s in the stats

Looking back to previous years, Santa Fe’s neighborhood had a total of two homicides in 2021, five in 2020, and three in 2019, according to reporting from The Kansas City Star. This ultimately diminishes any notion of a pattern forming from the initiative, merely marking 2022 as an unusual spike of violence in the neighborhood.

On top of this, statistics from the eight neighborhoods adjacent to the city’s most crime-infested show that violence within East Kansas City still remains at an all-time high.

These neighborhoods include Ingleside, Washington-Wheatley, Key Coalition, Oak Park Northwest, Palestine East, Palestine West and Oak Park Northeast, and Wendell Phillips.

The data used by KC 360 to report the reduction of violent crimes within the Santa Fe neighborhood is cut off when crimes are reported outside of neighborhood boundaries. The issue is that homicides or non-fatal shootings that occurred just across the street from the boundaries are left off of any statistics reported by KC Common Good.

While the Santa Fe neighborhood saw just a promising two homicides throughout 2023, a map of homicides throughout the metro tracked by Kansas City Star reporters shows that there has been a total of 15 homicides in just the surrounding neighborhoods.

The data shows that two of these occurred in the Key Coalition neighborhood, two in Wendell Phillips, and 11 among Oak Park Northwest and Palestine West and Oak Park Northeast neighborhoods.

Nine of those 11 occurred within the Oak Park Northwest neighborhood, just about a 10-minute walk south of Santa Fe. So, while homicides in the targeted neighborhood have decreased, just a couple of blocks away, they remain at an all-time high.

Accountability of progress

Public-facing information regarding the progress and statistics of KC 360’s program has been slim to none, as they recently marked a year of work. But that is all soon to change.

Earlier this year, the City Council set aside $30 million to be distributed over a five-year period for crime reduction efforts, which the Missouri Department of Health is administering distribution.

Of that $30 million, $1.3 million has been granted to UMKC criminal justice and criminology professor Marijana Kotlaja and her team to evaluate and track the progress of all programs that fall under KC 360.

Kotlaja and her team of five Ph.D. researchers and two computer engineers are developing a centralized data hub to hold all facets of KC 360’s joint violence initiative accountable. This public-facing statistics center is long overdue for an initiative that has already been in place for over a year.

“Most big cities do have a center, a justice institute that focuses on bridging the worlds of research and practice, and spreading violence prevention/intervention programs that have been determined to be effective,” Kotlaja says. “Down the road, hopefully, we can show just how important it is to have these evaluations and this research. Hopefully, as a city, we’ll be able to have a center that helps programs utilize the substantial body of research available to reduce violence.”

“I’m a huge advocate for having a center, kind of like a one-stop-shop, so you don’t have to put in requests each time you need crime data because it should be readily available to the citizens,” she says.

Beginning in January, the several programs that make up KC 360’s violence reduction initiative will be required to enter data regarding their progress to UMKC’s portal quarterly. As statistics roll in each quarter, Kotlaja and her team will analyze the progress made, with points such as each full year and, specifically, the fifth full year being large milestones to evaluate.

“That is what my team is going to kick off in January with all of these programs hitting the city in different areas,” she says. “We will be working with funded programs throughout the five years to evaluate them to say, ‘Hey, this is working right, this is not.’”

As the city continues throughout the new year, Kotlaja also plans on hosting lunch-in meetings with the numerous KC 360 programs to discuss their progress, hand out awards where they have been earned, and offer guidance through evidence-based literature.

“Hey, these other cities are doing this. What you’ve done is great, but let’s see if we can have a bigger impact by using some evidence to back up your program. And then we’re going to track that and see what happens,” Kotlaja says.

Applying these efforts today will not see a change tomorrow. But Kotlaja, as well as other city leaders, knows that there must be a foundation for the bridge to be built.

“It takes a while, especially with crime. I think for us in the short term, we could possibly see something in two to three years, but we’re talking year five or ten really to see the biggest effects,” she says.

With crime in the metro recently reaching an all-time high, there are still drastic changes that need to be made. As of right now, there have been 184 homicides in the Kansas City metro, topping the record-setting count of 182 that was reached back in 2020, marking the deadliest year in the history of the city.

Public figures across the city continue to urge members of the community to ‘play your part’ in helping reduce violence in our municipality.

“It can’t be in two to three neighborhoods; it has to be a citywide initiative. Educating the public is going to be important,” Kotlaja says. “One important long-term strategy for reducing violence will be implementing focused deterrence and urban blight abatement in communities that have been neglected in Kansas City and everyone doing their part to help those areas out.”

“We know through neighborhood research that if you increase community trust and engagement and improve place-based conditions, it can be very powerful to reducing high rates of violence.”

While some Kansas Citians may think that persistent crime on the Eastside does not affect them, they are vastly mistaken.

“Crime generates substantial costs to society at individual and community levels. So, if you have a city that has a high crime rate, businesses are not going to want to invest or remain in that city. We have a lot of important initiatives happening in Kansas City with the World Cup, with the Chiefs doing so well,” she says. “If we don’t get our crime rate under control, it’s also going to be more difficult for investors to want to come into our community. Crime affects everyone. Unfortunately, economics is one of the big things. But also, we know that we’re all better off if we can tackle crime.”

As citizens head into the new year, authoritative figures and the city as a whole are hopeful that the record set in 2020 will maintain the highest homicide rate that KC has seen to date. Work does not end there, however. The continuation of these programs and the launching of accountability will hopefully turn a tide in these trends.

Correction Jan 18, 2024 per email from Common Good PR: “KC Common Good did not receive or deploy this amount of public funding in 2022/2023. This figure ($426,890), was shared by KC Common Good in the October press conference and is the in-kind support that more than 10 nonprofit organizations and public agencies provided the Santa Fe community since KC 360 weekly meetings started (street intervention/support teams, social service supports, volunteer door to door outreach/canvassing, conflict mediation training, youth internships, etc.). $426,890 is a collective investment from partners, not tax payer dollars.”