Master of Horror Mick Garris on Sleepwalkers at 30 and Clovis the attack cat

[Panic Fest is KC’s premiere horror and science fiction film festival. Celebrating its 10th year, here is our full coverage of films making an appearance.]

Mick Garris has been knee-deep in the entertainment industry for over four decades. From starting as a journalist, to fruitful collaborations with Stephen King to hosting a beloved podcast, there isn’t much he hasn’t done. He’s been called both a “Master of Horror” and “the nicest guy in horror.”

He’s also a living legend and icon who has helped inspire generations of artists.

Garris is coming to Kansas City for Panic Fest, where he will host a 30th Anniversary screening of Stephen King’s Sleepwalkers. Ahead of his appearance, we discussed many points of his career, though the topic often shifted between great stories and insightful commentary on horror filmmaking and being a genre fan.

The Pitch: You’ve done notable work in the film industry for decades, wearing a lot of different hats. Usually when that happens, that means there’s some odd IMDB credit that sticks out. We have to ask, what’s up with these voice acting credits for The Pink Panther (1993) cartoon show?

Garris: Yeah, that’s how I got my SAG card! It was doing voices on two of The Pink Panther episodes. Matt Frewer—who was in The Stand—myself, and our makeup effects guy, Billy Corso all did voices back and forth with each other.

Matt was hired to be the voice of The Pink Panther, and he asked if I would like to come and watch a recording session. I was thrilled, because I’d never been to a voice session for a cartoon before. What I didn’t realize was that he had talked to the producers about that before, and then after the recording session, which was amazing.

Dan Castellaneta and all these different really famous voice actors asked me to stay and go in the booth and threw a bunch of voices at me. You know, “What would a horse sound like, who’s singing, and who’s been locked in a barn?” Or, “What does a rich uncle sound like?” All these things.

They hired me to do two episodes. I did three voices on each. That is the extent of my voice talent.

In addition to your extensive filmmaking work, you’ve also doubled as a journalist, and that morphed from various talk show formats to your Post Mortem podcast. Have you held onto that because you enjoyed doing it early on?

To be able to talk to people whose work I admire, I assume that there’s an audience out there that’s as interested as I am in that. I feel like I’m kind of a conduit in that way, too, because it’s a show that is hosted by a filmmaker rather than a journalist. There’s a different perspective there. There’s a way that filmmakers open up more when they’re talking to somebody who really understands that perspective, from the inside.

I’ve learned a lot from literally every show I’ve ever done. Whether it’s a director, or an actor, or a makeup effects guy, or whatever. I also just love movies. And I love sharing that enthusiasm with other people who make them. I assume that the audience is there, as I would be, if I weren’t doing this myself.

I think your love of film is important for lots of people. Where did that come from for you?

I think a lot of people who make movies, love movies, or are journalists in the film world do it because they’re often loners, like me. They are often people who don’t have a rich social life and lose themselves in the arts, particularly in the terms of horror movies and genre movies. You feel like the outsider, and you identify with Frankenstein’s Monster more than you do with the people who wanted to burn him at the stake.

I was very much an outsider. I had two brothers and a sister, and then later on two more sisters and another brother, but I was very much a loner. We were not a really socially tight family. My older brother was an athlete. My younger brother’s interests were cars and flowers. My sister joined the Navy when she was old enough. I was always the one drawn to cartoons, imagination, and the fantastique of movies and TV.

So, it is something I found solace in, because I didn’t have a lot of friends. These became my family. My parents split up at an early age, so we were kind of on our own, and we each sought out different education, entertainment, or social graces all of those things.

Now, people can find communities, because not only do they have access to these movies, but they have social media where they can find people who share the same interests.

It’s a way to connect to the people you didn’t have before, through social media. But there’s also another really important point that ties in with film festivals, such as Panic Fest, which is that the horror genre is the only one that has consistent conventions and film festivals.

Horror fans and fantasy fans, they want to own the movies that they love. They want to feel like a part of them. They want to get every edition on Blu-Ray and 4k and all of those things. When they gather, they come together to see so-called celebrities within the genre—to see the movies in a shared experience.

They can go to a theater and see movies projected on the big screen, as God intended, with like-minded people in that audience. You know, you have access to some of your idols there, and you can get their autographs, get your picture with them, and things like that. Really share in the art that you’re so attracted to.

They don’t have comedy festivals like that. It’s all about showcases that go on television. But these conventions we’re talking about, all around the world, where they get together to honor horror films from now to the earliest of their beginnings—they don’t have those for other things.

Of course, the reason we’re having this conversation is that you’re coming to town for a 30th anniversary screening of Stephen King’s Sleepwalkers, which is a film you’ve had an interesting relationship with over the past couple of decades.

You know, this one is kind of remarkable. It’s the only movie I did that was number one at the box office on its opening weekend. It was Stephen King’s first original screenplay to be produced that was not based on one of his stories or books. It’s a rather bizarre film. I just saw an article calling it “The Weirdest Stephen King Movie Ever,” and I wear that badge with pride.

The reviews were terrible for the most part when it came out, and it’s being remembered fondly because it is an odd duck. But yeah, it was my first and last studio film as a director.

Most of my work since then has either been on a smaller independent scale or on a large scale for television, like the mini-series we worked on. This was the first time I worked with Stephen King out of what ended up being eight or nine times. It was the beginning of a great creative and personal relationship that I will always cherish.

Something noticeable when re-watching is that you can still feel a “King-ness” to it. You can still see his narrative style coming out, jumping from multiple characters throughout the story. At the same time, there’s a great sense of humor to it all.

We embraced the ludicrousness, and there are some funny lines that King had written into it. Though, you know, everybody from King to me, all the way down the line, took it seriously and played it for all its worth.

The more you play with the broadness of comedy, the more you iron out the laughs, and the ridiculousness is played straight. That gives us a great sense of humor.

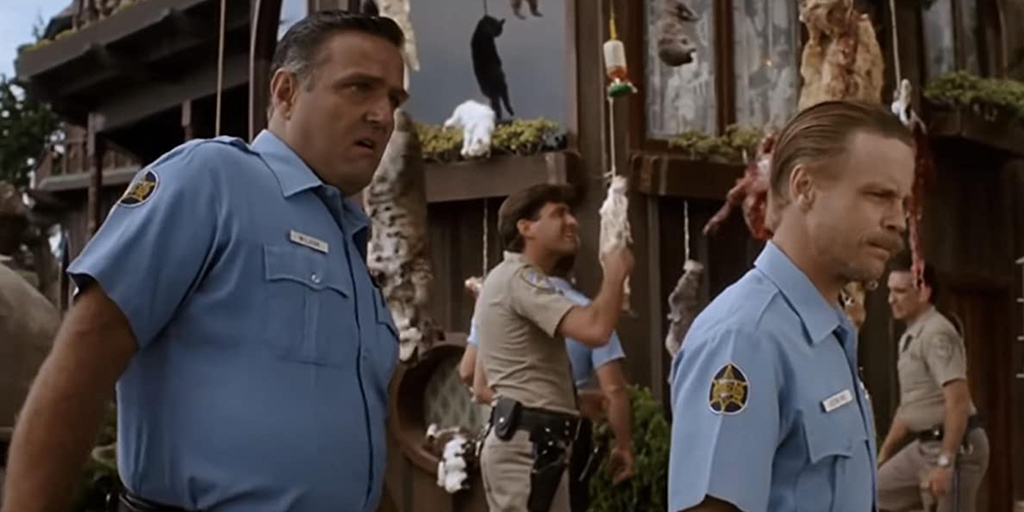

And then you also have a relationship between a police officer and his attack cat partner.

Yes! Clovis the attack cat.

I think that’s one of the best scenes of the movie. When Clovis is laying down on an individual, you feel your heart sink.

That scene—it worked out so well. The cat was so good at it. There is a character that’s killed, and it’s a brutal death. The cat who’s there trying to protect him ends up in pain, in sorrow, crawling on top of his chest and curling up and purring, just trying to be close to him. How did we get that on film?

That cat was such an amazing cat. His name was Sparks, by the way. Nine cats were hired to play Clovis. Each of them would have a specialty, whether it was purring, jumping, running, or hissing. Sparks did every shot in the movie except for two hissing shots that another cat did.

With the trajectory of your career, you have people who literally grew up with your work. As kids, there was Batteries Not Included, Fuzzbucket, and Critters II. Then those same people were in high school when The Stand came out.

By the time we were doing The Stand, it was going to a much broader audience. It was the highest-rated mini-series in history. Millions of people saw it each night. More of them watched it each subsequent night than the preceding night. So, it became something cultural.

With access through various streaming formats, it’s easy for mini-series or short series to just kind of pop up out of nowhere. Do you feel like that has minimized the format?

There’s no water cooler effect anymore, unless it’s something like the Oscars or a football game, or something that everybody has to watch at the exact same time. There’s another element to it though that has changed everything. Streaming. Every series is a mini-series now because they are all serialized.

Originally, when a TV series was on once a week, every episode was a standalone episode.

Now that people stream everything, you can watch it all in one week or in one day. It doesn’t have to be a self-contained episode every time, compared to when it was a weekly affair. There’s almost no such thing as “standalone episodic television.”

You’re also seeing the return of the anthology series, which of course is something that you’ve been tied to over the years, whether it’s with Masters of Horror or Nightmare Cinema. What do you like about that format?

Every episode is a self-contained movie. They don’t have anything to do with each other. When I created Masters of Horror, the idea was to get the best filmmakers who were still alive and working in the horror genre and set them free to do whatever they wanted within the financial realm and the reality of series television.

So, you’d get a John Carpenter film that looked, acted, and played like a John Carpenter movie. You’d get a Tobe Hooper film that looked, played, and acted like a Tobe Hooper movie. I was able to adapt Clive Barker’s stories to the screen. I was able to bring Richard Matheson’s stories to the screen. We’d get people like Dario Argento from Italy. We got Takashi Miike from Japan to do things that were really exceptional. That could only have been made by them.

The idea of individual cinematic personalities being represented on the small screen was thrilling to me and still is, and I’m working on another right now that I hope to get off the ground shortly. I’m working on something with a very well-known figure in the horror field. We’re creating something with all new and original stories that will all go together in a 10-episode anthology series.