Lemony Snicket popped by to revel in Kansas City’s Explor-a-Storium

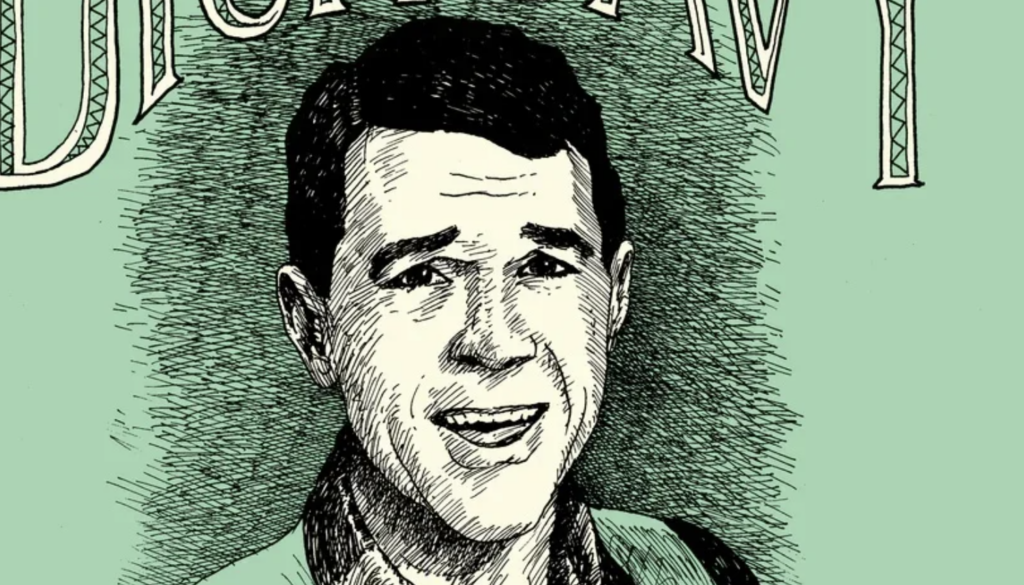

Daniel Handler is an author best known for A Series of Unfortunate Events, a 13-book children’s saga published under the name of its macabre narrator, Lemony Snicket. When Handler began his journey with the series, literary professionals raised their hackles at the grotesquerie that makes the books so whimsical and singular.

In particular, they latched onto a scene in which a baby is gagged by the villain, stuffed into a birdcage, and dangled out of a high window.

“When A Series of Unfortunate Events was just starting out and I was on tour,” says Handler, “there were quite a few booksellers and librarians who were nervous about my books and sometimes found them objectionable. And the question that was asked the most was, ‘Do you have to put a baby in a cage?’”

While on that tour, Handler journeyed to Kansas City for the first time. After arriving at his hotel late at night, he decided to wander out and peek in the window of the children’s bookstore that would be hosting his book event the following day.

“I walked over to the bookstore, and it was midnight so the bookstore was closed,” says Handler. “But I could see right through the door that they had made this [paper mâché] baby in a cage just for me. I knew that I was in a special place.”

That special bookstore was the revered Reading Reptile, where the birdcaged baby hung for more than a decade. Run by artists Pete Cowdin and Debbie Pettid for over 30 years, the Reading Reptile gained national acclaim and had storefronts in Westport and Brookside.

While Handler’s decades-long friendship with Cowdin and Pettid has outlived the store—which closed for good in 2015—there isn’t an end in sight to their hare-brained undertakings.

Now, he’s part of the national advisory council for The Rabbit hOle, a non-profit museum focused on children’s literature co-founded by Cowdin and Pettid. It also claims the title of “The World’s First Explor-a-Storium.”

Handler (Left) with Cowdin (Middle) and Pettid (Right) at the Pick Your Poison event. // Photo by Travis Young

Since 2015, the Rabbit hOle team has been building exhibit prototypes, designing mobile pop-ups, and contributing to the city’s literary programming. They were temporarily housed in the Crossroads Arts District until 2018, when the museum purchased a 165,000 square-foot building in North Kansas City. Currently, the building is under renovation as they’re hard at work constructing the exhibits.

While the pandemic set their production timeline back—as it did for many arts organizations struggling to procure funding—they’re looking at possibly opening by early 2023. The final product will feature a litany of exhibits and programming areas: a letterpress print shop, maker-space, resource library and reading room, cafe, history panorama covering 100 years of children’s literature, writing and story labs, gallery spaces, and, of course, a bookstore.

Part of Cowdin and Pettid’s motivation for closing the Reading Reptile was to pursue this grander vision. Because why have just a bookstore when you could have a 165,000 square-foot museum with a bookstore inside?

“We love the books and art, and weren’t as fond of the business side of it,” says Pettid, of the professional pivot.

Cowdin concurs: “Both Deb and I were getting exhausted by the market-driven aspect of bookselling, as opposed to just finding something we could do that departed from that aspect of our lives, and getting more into the joy of reading.”

Bookselling fatigue was not their sole motivation for shuttering the Reading Reptile, though. The pair has an unparalleled vision for a destination that will ignite a passion for literature in children while engaging parents and guardians along the way.

“We had lots of experience with books and kids and environments and discovery—and we knew we could create something that was beyond what people were imagining to bring kids to become readers,” says Pettid.

Claiming “lots of experience” is an understatement for this duo. Cowdin, for example, is awed by his colleague’s expansive working knowledge of kid’s books.

Stairs from the My Father’s Dragon-themed central staircase at The Rabbit hOle. // Photo by Travis Young

“Everybody who knows Deb, whether they’re an author and illustrator or publisher, knows that she knows more than probably anybody, about not just books… but the relationships between authors, between different eras of bookmaking, printing processes and how they informed the results of a book in their making at that time—things like that. I think a lot of people achieve that through academic processes, by getting a Master’s or a Ph.D. Debbie’s done it just by—”

At this point, Pettid cuts in with: “Lying in bed and eating potato chips.”

Perhaps potato chips are the secret ingredient for the co-founders of The Rabbit hOle, whom Handler refers to as “titans of children’s literature.”

“I mean, only they can do it,” Handler remarks. “It is such an individual vision, even though it is made of many, many other people’s individual visions. It has the freaky individualism that artists produce.”

Early in December, The Rabbit hOle welcomed Handler back to Kansas City for a series of decidedly fortunate events. These included Pick Your Poison, an evening of philosophical discussion in honor of his new book, Poison For Breakfast.

Published under Lemony Snicket’s name, this pocket-sized volume is a completely true philosophical murder mystery. (For what it’s worth, the library shelves it in the non-fiction section.)

The evening itself was punctuated by moments of profound conversation and piano accordion performance, courtesy of Handler. A staff member wheeled a cart around that read, “Is life me? / Is life you? / Is life we?” where guests were invited to submit philosophical questions for the author.

When asked whether a storyteller should be honest, he provided his most succinct axiom with no hesitation: “No.”

For the rest of the night, guests were free to roam the first floor of The Rabbit hOle like children set loose in the Chocolate Room of Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory. There were skeletons of slides tunneling through installations, and a giant hamster wheel that, at some point, will embody Little Toot.

Folks meandered through the fire station from The Fire Cat—replete with a child-sized fire pole—before mounting a staircase made to look like the lush jungle from My Father’s Dragon. It is as if Harold and his purple crayon have had their way with the space, animating every character within reach.

Every last detail inspired wonderment and heady fascination—the scene was made all the more intoxicating thanks to the open bar, as well as the neighboring cereal and milk bar. Slurping on oat milk and Froot Loops, I thumbed through a bookmarked copy of Goodnight Moon that someone had placed on a replica of the bedtime tale’s famous rocking chair.

While there are still thousands of feet of empty space, it was not hard to look around and picture the final product. As it is now, the exhibits are sprawling and associative. This will continue to be the driving approach, per Pettid’s curatorial vision.

“We wanted to cover [books from] 1900 to 2000,” says Pettid. “We wanted to capture people who had influence on others in the industry. Maybe they didn’t have the most popular book, but maybe they were mentors, or important in other ways. We wanted to make sure that there is a diversity of gender and ethnicity and age and subject matter. It’s kind of putting together a big, giant puzzle, and making sure that everything fits, and moving things around all the time.”

Pettid is also quick to clarify, “I’m not saying like, ‘These are the best 50 books of the last century.’ It’s more nuanced than that. But I think it will create lots and lots and lots of layers of discovery and contact points.”

These opportunities for discovery are shaping up to be different for each and every book.

“We can’t build every exhibit out from cover to cover,” Cowdin explains. “We’re going to be doing it on a temporary basis in the immersive gallery where we’ll put in a full book landscape where you can move through that story. But for each permanent exhibit, we have to find a place in the story that’s going to deliver the most narrative.”

Pettid points to their sculpture of Katy Kangaroo No-Pocket from the book Katy No-Pocket that stands over eight feet tall. Armed with her smock full of pockets, Katy greeted guests at the door as they arrived for Pick Your Poison.

“You saw Katy [Kangaroo] who’s just, like, a giant kangaroo. I mean, that’s all you need. [The story is about] a kangaroo with no pockets, so she gets a lot of pockets,” says Pettid, shrugging at the deceptive simplicity of the idea. “Sometimes it’s just something like finding a really key moment or key illustration that everybody visualizes when they think of that story.”

Some of the exhibits will be immersive walk-through experiences, with text incorporated. Others, like Katy No-Pocket or I Want My Hat Back will focus on stand-alone characters. Some exhibits will even read the story aloud to you, as is the case with the Last Stop on Market Street bus.

Last Stop on Market Street is the tale of a grandmother taking the bus with her grandson while answering his barrage of his questions. As of yet, it’s the only 21st-century book represented in the museum. For this installation, the Rabbit hOle team has constructed a vehicle-sized bus into the NKC building, which Pick Your Poison attendees were welcome to board.

The ride costs a small bus fare, of course, which was donated to Thelma’s Kitchen. After taking your seat alongside the sculptured characters, the bus began figuratively rolling, as screens installed in the windows played an animation of the story complete with audio narration.

“I think you never love a book the way you love a book when you’re 10 years old,” says Handler. “You can live, when you’re loving a book, in a liminal space where you’re in the story and you’re thinking about the story and you’re altering the story… You begin to negotiate different boundaries as you’re playing with the story in your head, and I think The Rabbit hOle makes that very literal. You get to sit in the bathtub with Harry the Dirty Dog and think about that for a minute.”

One gets the sense that the Rabbit hOle team is dreaming their wildest dreams while sitting crisscross applesauce on the floor of their 165,000 square foot Explore-a-Storium. As they exercise their understanding of the ways kids interact with story and illustration, they try to look at their museum as if they’re curious children themselves.

“We’re providing a new entry point to develop a relationship with story and literature,” says Cowdin. Pettid continues: “If I was a kid and I’d read the book Fire Cat, or I just looked at the book Fire Cat, I want to go into the firehouse. I don’t want to be told that this is Fire Cat’s house, because I know it is already. For a kid who doesn’t know the book, they just go into it and have this discovery of this part of the story, and then they want to know the rest of the story. It’s about developing curiosity so that they come to the book on their own.”

By facilitating this process of discovery, The Rabbit hOle is promising to deliver an experience that diverges from that of many other children’s museums.

Cowdin and Pettid make it a habit to research and rigorously interrogate children’s museum—and adult museum—trends, especially when it comes to inclusivity and guest experience. What family-engagement tactics seem innovative? What are other children’s museums leaving to be desired?

“There are things that are also warning signs for us of complacency in that industry,” Cowdin says. “Debbie’s always said from the beginning, we’re not going to be the museum where you’re banging buttons.”

The pair was inspired by the City Museum in St. Louis, as “you cannot go to the City Museum and not participate.”

Cowdin and Pettid gave themselves the added challenge of making their children’s museum a space that will excite parents and guardians as well.

“Reading Across the Nation: A Chartbook (2007)” from the Reach Out and Read National Center in Boston reported that “[f]ewer than half (48%) of young children in the United States are read to daily.” Cowdin says that from the ‘90s to now, this statistic hardly changed—but the Rabbit hOle team wants to see it increase.

“[The Rabbit hOle] is very different than going to LEGOLAND, or a lot of just general children’s museums, where a kid goes into a room and starts playing with a Lego, and the parent is over on the side and checks their email,” says Cowdin. “That’s not what this is. This is about people coming into the experience, where there’s an emotional attraction, and a spiritual attraction to the books they know from their childhood. That’s the dynamic we’re trying to create—where it becomes irrepressible, like you can’t not participate in then sitting down and reading the book.”

At the same time, they are cognizant of barriers that may prevent adults from reading to the children in their lives. Hence why not all exhibits are focused on reading the text.

“There are many parents who don’t have the capacity [to read to their children],” says Pettid. “Whether they’re working two jobs, or maybe English is their second language; or maybe they just don’t read, they don’t have access to books. So part of that is creating a space where, if a parent is unable to read, they’re still going to feel comfortable and safe in our space.”

The “spiritual attraction” that Cowdin describes—the realization that you cannot do anything but have an adventure—worked its wonder on the crowd of adults attending Pick Your Poison.

When one guest spotted the plaster silhouette of the peddler from Caps For Sale, outlines of his dozens of hats drafted in pencil above his head, their eyes grew wide. They gasped, pointed, and grabbed their companion’s arm to draw them closer.

Part of the magic of these installations, though not obvious to the naked eye, is that every last component is being made on-site. The Rabbit hOle employs (and is actively hiring) a host of creators for the fabrication shop: upholsterers, painters, digital designers, foam sculptors, metal workers, and more.

Their team includes Kansas City Art Institute graduates and even Scribe, a muralist whose work decorates the streets of our city.

These efforts are atypical for many children’s museums, which tend to outsource this type of construction labor. For The Rabbit hOle, this approach is necessary, due to the intimate collaborative process they’ve developed with the creators of the yarns they are bringing to life.

“That’s one of the big reasons we are creating all of the exhibits on-site—not just because it’s financially feasible, a lot cheaper for us to build exhibits on our own and invest in people—but because we have to be respectful and responsive to a variety of expectations that come with every book,” says Cowdin.

Currently, The Rabbit hOle has obtained the rights and permissions to over 70 children’s books, and the processes for making the stories three-dimensional are as individualized as the illustrations that fill their pages. In some cases, the estates of creators give their sign-off easily, asking only to see the final product. In others, the creator wants to be consulted at every step of the production process. The Rabbit hOle team welcomes this collaboration and at times, specifically requests it.

“A good example of an exhibit we’re working more with the estate is the John Steptoe Uptown and Mufaro’s Beautiful Daughters exhibit, where there’s an African American experience of Harlem,” says Cowdin.

The museum team is at work constructing a city block from the Uptown, which will give museum-goers the opportunity to actually step inside the buildings.

Cowdin explains, “We need [the children of Steptoe to provide] their input. They need to become the sort of lead on that because we don’t pretend like we know what that was like or have that same experience.” Pettid agrees: “[We need them] to curate the space.”

Due to the team’s sprawling national vision and the broad buy-in they have secured, The Rabbit hOle is set to be a popular tourist destination. At the same time, they are focused on maximizing their educational and community impact through local partnerships.

“[We] will only grow in terms of our relationships with other museums because we will be programming with other institutions, whether it’s The Nelson-Atkins Museum, [The National Museum of Toys/Miniatures], Wonderscope, or anywhere,” says Cowdin. “We see a lot of siloing going around Kansas City in the past, as far as institutions sort of holding their own, and we would like to see that through a different lens of collaboration.”

These relationships will also help The Rabbit hOle create a museum that prioritizes accessibility for the local community.

“To make it accessible, you have to understand, it’s not just about cost or money, it’s about how a family’s going to find out about [The Rabbit hOle], and how a family is going to get there,” says Pettid. “A lot of organizations treat accessibility with field trips, and field trips are one way to get a wider, more diverse audience of students. But the real challenge is: how do you get those families to come?”

Her question is answered, in part, by creative programming that isn’t restrained to arts organizations. For example, weeklong family passes to The Rabbit hOle will be available for check-out at the Kansas City Public Library. Branches will organize Saturday trips to the site for families, with transportation provided by Kansas City Area Transportation Authority.

“The focus is about helping kids and families,” Pettid says. “Adults also understand that they have stories, and the value and importance of their story.”

As for the kids, it’s about investing in their cultural spaces with sincerity.

“Children’s culture is diminished in large part by adult culture, or lives under the shadow as some sort of secondary culture—and it’s not,” Cowdin says. “The work we do with books when we’re selling them, and the work we’re doing now with The Rabbit hOle, acknowledges that this is an art form.”

As an adult in the industry, Handler has also experienced this subjugation of children’s culture.

“I meet a lot of adult authors who are surprised when I know about literature and what I’ve read because I think they assume I’m in some way a clown you hire for a birthday party,” he says.

For Handler, The Rabbit hOle provides a validation that is necessary to a healthy and flourishing imaginative life.

“I think [The Rabbit hOle] helps you realize that imaginary space is really important. I think that our imagination gets chased away from children a lot,” says Handler. “You want to look at every building that Curious George has visited, you know? You want to go inside the firehouse, you want to open the stomach of the bear [from I Want My Hat Back]. And that can serve as a reminder of how important your imagination is really important—you’re part of this space that gets devalued a lot by a lot of forces in the culture.”

At The Rabbit hOle, “adult culture” will be relegated to the sidelines as parents and guardians are invited into a world where childlike imagination is on full display, and anyone over the height of five feet must stoop to clear the doorways of the exhibits.

In this way, Cowdin, Pettid, and the Rabbit hOle team are ringmasters, inviting families and curious personages to step right up for sights unseen and feats beyond your wildest imagination.

All the while, a paper mâché baby in a birdcage hangs from the ceiling of a staff-only studio on the second floor—a maidenhead of good fortune for the voyage.

Starting this month, The Rabbit hOle will be entering the final phase of building renovations, while continuing to produce the exhibits. You can support the Explore-a-Storium through financial support or introduction to financial support, signing up for newsletters, and following their progress as they hop along on their Instagram. Learn more about ways to donate through their website.

Books referenced in this article include A Series of Unfortunate Events written by Lemony Snicket and illustrated by Brett Helquist; Poison for Breakfast written by Lemony Snicket and illustrated by Margaux Kent; Willy Wonka & The Chocolate Factory written by Roald Dahl (illustrators vary depending on the edition); Little Toot written and illustrated by Hardie Gramatky; The Fire Cat written and illustrated by Esther Averill; My Father’s Dragon written and illustrated by Ruth Stiles Gannett; Harold and the Purple Crayon written and illustrated by Crockett Johnson; Goodnight Moon written by Margaret Wise Brown and illustrated by Clement Hurd; Katy No-Pocket written by Emmy Payne and illustrated by H.A. Rey; I Want My Hat Back written and illustrated by Jon Klassen; Uptown and Mufaro’s Beautiful Daughters: An African Tale written and illustrated by John Steptoe; Curious George written and illustrated by H.A. and Margaret Rey.