Douglas K. Miller’s book Washita Love Child shines a light on Indigenous guitar legend Jesse Ed Davis

Despite an astonishing discography–multiple albums with Taj Mahal, the guitar solo on Jackson Browne’s “Doctor My Eyes,” touring with the Faces, his own solo albums, and so much more–the work of Kiowa-Comanche guitarist Jesse Ed Davis is mostly only known to musicians and the sort of music fan who digs deep into liner notes to figure out who played on what.

That will hopefully all change with the release of writer Douglas K. Miller’s new book, Washita Love Child: The Rise of Indigenous Rock Star Jesse Ed Davis. Tracing Davis’ life from his birth in Oklahoma, through his time in Los Angeles and California, and many stretches of highway in between, Washita Love Child makes the case for Davis paving the way for many, many artists who would come after him.

In addition to tracing Davis’ family history via the historical record and family interviews, Miller speaks with nearly everyone who worked with Davis over the years, including Taj Mahal, Jackson Browne, Rod Stewart, and the Doors’ Robby Krieger, to name but a few. Despite Davis’ tragic end, Washita Love Child is a celebration of the guitarist’s life and career, as well as kicking off many other explorations of his work.

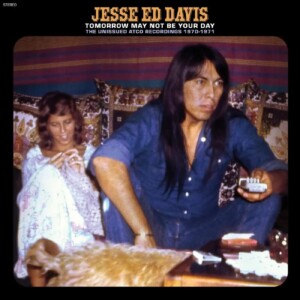

In addition to Miller’s book, out this week from Liveright, an exhibition celebrating Jesse Ed Davis’ life and work entitled “Jesse Ed Davis: Natural Anthem” opens to the public at the Bob Dylan Center on Friday, November 15. Additionally, Real Gone Music will release Tomorrow May Not Be Your Day–The Unissued Atco Recordings 1970-1971, a limited edition double vinyl LP for Record Store Day Black Friday, comprising many previously unreleased recordings discovered during Miller’s research for Washita Love Child. There’s also an all-star concert featuring past collaborators Jackson Browne, Taj Mahal, Joy Harjo and the Grafitti Band set for February 6 in Tulsa.

It’s an absolute embarrassment of riches, and we spoke via Zoom with author Douglas K. Miller as to how all of this came to be.

The Pitch: How did you come to Jesse Ed Davis’ music to such an extent that you spent five year working on this book?

The Pitch: How did you come to Jesse Ed Davis’ music to such an extent that you spent five year working on this book?

Douglas K. Miller: I’ve been aware of Jesse Ed Davis for a long time, just growing up on classic rock FM radio. You know, my earliest memories in life as a devoted fan of music and a musician myself, is listening to old Jackson Browne records and Bob Seger and Queen and stuff like that, that my parents would play.

“Doctor My Eyes,” I’ve been listening to that tune since birth, essentially, so Jesse’s always been there for me. And as I got older and really started to explore music at a deeper level, I saw his name pop up on records that I liked. It was one night in I don’t know, 2016-17, sometime around then, I was listening to Gene Clark’s White Light album and Jesse produced that.

It’s a really great album. It’s one of these rediscovered, lost, classic albums. I was just sitting on my couch listening to the record and I thought, “Why don’t we know more about Jesse Ed Davis? I see his name all the time. I’m an avid reader of rock music books and jazz and blues and country and I never see anyone discuss him meaningfully,” and I thought, “Well, maybe I’ll do a book about Jesse Ed Davis when my first book is finished.”

My first book came out in 2019 and I still didn’t know if I was serious about this, or if it was just kind of a funny idea that I had. I got started on it, wondering if I could maybe just pull together an article, because I didn’t think there would be enough out there for a book. I thought the reason we didn’t have one was because maybe it couldn’t be done. Before I knew it I had more material than I could fit in this book.

The amount of people you were able to contact is astonishing. Who was the first person you spoke with?

I’m astonished by it too. And I should mention that, on one hand, I’d like to think that I was kind of savvy in that respect. I think being a musician myself maybe made people a little more comfortable speaking with me, but it was also in the context of the pandemic when I really got going on the interview, so people were home and some of them were like, “Yeah, let’s talk. There’s nothing else to do.”

I can tell you that the first thing that I did was reach out to one of Jesse’s family members, who’s based in Oklahoma City. This was right before the pandemic really struck, and we got together for lunch, and she gave me her blessing to work on the project and gave me a little help getting going on it. From there, I emailed Jackson Browne’s manager. I’m a big fan of Jackson Browne and even that I thought was kind of silly. Like, “I won’t get a reply on this,” and I did.

She wrote back and said, “Jackson would love to speak with you for a book about Jesse Davis,” so I had that in my pocket. From there, Jim Keltner, the great drummer, who’s played with everybody. I don’t know who he hasn’t played with. John and George and Ringo and Tom Petty and Neil Young–I mean, you name it, Jim Keltner, who was a hero of mine growing up as a drummer. I got a contact for him and called him, and he said yes.

I did a couple of interviews with him, and at that point, I had a couple of people with real stature in music history and in the music business behind the book, and that opened so many doors for me. To say that Jackson and Jim Keltner were on board made a lot of people interested in talking to me, so I really credit the two of them with getting behind the book in the early stages.

You mentioned in the book that, as you were doing some of these interviews and reaching out to folks, folks were asking, “Well, have you talked to Taj yet?” It seems that once he got on board, that really opened the floodgates, just given their brotherhood, if you will.

Yeah, hat was central too. In fact, it was through the connection with Jackson that I ended up getting. Contact for Taj. I called Taj, left a voicemail, and he called me back while I was in the middle of lecturing in my US history class. I always have my phone up on the console so I can see what time it is and I saw a call is because it’s vibrating and I looked over and it said Taj Mahal because I’d already put his contact into my phone. I was trying not to freak out in the middle of a lecture.

I tried to go to Taj first for anything, like the tribute concert that we’ve planned for February 6 at the Tulsa Performing Arts Center. The first person I reached out to in my part in organizing this concert, I messaged Taj. I mean, he has earned the honor and respect and his years working with Jesse were so foundational in Jesse’s success in the music business that Taj’s support meant everything.

You mentioning that concert brings up the fact that it’s not just this book. There is the exhibition that starts very soon at the Bob Dylan Center, “Jesse Ed Davis: Natural Anthem.” There’s the album that comes out just two weeks after that, Tomorrow May Not Be Your Day. You’re involved in both of those so it just seems as though this book is the icebreaker to make November Jesse Ed Davis month.

You mentioning that concert brings up the fact that it’s not just this book. There is the exhibition that starts very soon at the Bob Dylan Center, “Jesse Ed Davis: Natural Anthem.” There’s the album that comes out just two weeks after that, Tomorrow May Not Be Your Day. You’re involved in both of those so it just seems as though this book is the icebreaker to make November Jesse Ed Davis month.

One thing led to another. When I was working on the book, I connected with one of Jesse’s friends toward the end of Jesse’s life, who worked for many, many years in the Warner/Electra/Atlantic archive. He invited me to go into the archive and to see Jesse’s analog tapes, his masters. When I was there, we pulled down tape boxes, and it was so cool.

It’s like Jesse Davis, Aretha Franklin, Frank Sinatra. Just to see Jesse and the company that he was in with his major label deal was impressive enough and then, when we were looking at the tape boxes, we were starting to see that there was a bunch of like–we were showing each other, like, “What’s this song? I’ve never heard this. I didn’t know he recorded this” and that led to that project, but I was really in there as a researcher for the book.

My partner and co-producer, Mike Johnson, did work on his end and next thing we know, we were doing this album, which I embraced as a way to learn more about Jesse’s recording process and how he functioned in the studio, to say nothing of just getting to hear a bunch of music we’ve never heard before.

The exhibit was an extension of the book. Joy Harjo is the artist in residence at the Bob Dylan Center, and she had mentioned that she wanted her first major project to be on Jesse Davis. They said, “Great. We know a guy over in Stillwater putting out a book on Jesse. You two should meet. ” The concert was an outgrowth of the book and the exhibit.

If we’re going to do an exhibit, we probably need some music and we were sitting one day, imagining what we could do for a concert and I mentioned Jackson Brown and Taj Mahal. We should start there. And the Grafitti Band, maybe? Those were our first choices and they all said yes. Amazingly, the Grafitti Band is going to reunite and play under that name for the first time since 1988. Jackson and Taj are not on tour. They’re coming out to Tulsa just to do this concert for Jesse, which speaks volumes about. their relationship with him and their concern for his legacy. It’s really exciting in terms of Jesse Davis’ legacy.

Reading the book, I noticed that everyone was very open and willing to speak with you about both the highs and lows of their relationships with Jesse, and you do a really great job of balancing them. How do you walk that line, where you’re protecting the legacy of someone? Also, since this is the only book about Jesse Davis, how do you make sure that you’re presenting everything in a very balanced way?

That’s a good question, and it speaks to perhaps the greatest challenge of the book. As you mentioned, it’s not like I was writing a book about John Lennon, and there are 172 other books that I could have consulted to find my way into some fresh material or something. I was starting with almost nothing.

There are a couple of internet articles. A couple of brief magazine write-ups have trickled out gradually over the years. There’s a 10-minute clip in the film Rumble: The Indians Who Rocked the World. As a professional historian, I didn’t have a body of work that could help motivate the questions that I was asking and orient me to the subject.

The challenge is in the book, right? When I got started on this, a few people I spoke to said something to the effect of, “You’re not the first person who tried to do a book on Jesse.” Oh, really? Wow. So somebody did try to do this. I don’t know who they were. Nobody ever told me the names. I don’t know what happened to them. I realized quickly why maybe some people had tried and couldn’t get very far. More than one person, I think, even use the specific terms said that, “Whoa. A book on Jesse? That’s a minefield.”

This is somebody who died from a heroin injection in 1988. How the heck am I going to write this story and not unwittingly reinforce stereotypes about Indigenous peoples and substance abuse? How will I write this story and not have it be one in which the tragedy and the death are the story, and it’s all-consuming, and everything is always leading up to that moment? How do I celebrate his significance as a Native American historical subject and all the great work that he did as a musician without having it be all about the darkness?

What I tried to do was take up those more difficult subjects and contextualize them so we see Jesse as a person who’s in the popular music business in the 1970s, where drugs are a prominent feature of the culture right down to, as I suggest in the book, some people got paid in drugs. I mean, that probably doesn’t surprise us. We know those kinds of stories, but I didn’t want to sensationalize it or fetishize it. I talked about Jesse’s battles with drugs as being a disease and I often in the book would use the words “Jesse is unhealthy. He’s becoming unhealthier. He’s becoming unwell” or “Jesse’s sick.”

I’m not trying to characterize him as this tragic drug casualty. I’m trying in the book to understand what happened at that end of his life and make some suggestions on why that happened–meanwhile, always trying to emphasize the work that he was doing as a musician. Even when he was struggling most with addiction, he was still productive. Even when he was in Hawaii on what was supposed to be some kind of retreat, he was battling addiction there, but he’s working with Gene Clark. It’s on a club level, but he’s working and he’s producing local artists.

I’m not trying to characterize him as this tragic drug casualty. I’m trying in the book to understand what happened at that end of his life and make some suggestions on why that happened–meanwhile, always trying to emphasize the work that he was doing as a musician. Even when he was struggling most with addiction, he was still productive. Even when he was in Hawaii on what was supposed to be some kind of retreat, he was battling addiction there, but he’s working with Gene Clark. It’s on a club level, but he’s working and he’s producing local artists.

Of course, in ’85, he’ll hook up with John Trudell, and they’ll form the Grafitti Band. I call this a second career peak in Jesse’s life that happens right before he dies. So, right, I’m always trying to explain to the reader what happens without getting too deep and not getting too melodramatic about it, but I had to tell the reader just enough about Jesse’s health for the story to make sense.

If I didn’t say enough readers won’t understand: “Well, how come he’s not in the studios anymore and doing a bunch of session work?” I needed to bring the reader along and talk about Jesse’s battles on that end in a way that would make sense without having it take over the story. Finally, there were times where I tried to step back with my author’s voice and let other people speak about what they were experiencing with Jesse and some of the tougher dimensions of his story and his death itself.

I really stepped back in the chapter where he dies and I let all those other voices come in and kind of take over. I did that on purpose. In doing that, I try as much as possible to tell the truth about Jesse’s story. The truth is always more interesting than lies or mythology and things of that nature. If no one’s ever done this before–if there’s never been a book about Jesse–then maybe the worst thing I could have done would to go into it and be really dishonest with it.

Hopefully, this produces more work about Jesse down the line and different people can tangle with different elements of his story in different ways, but the one thing that I was trying to do in the book was, as you suggested, elevate Jesse is an important figure and popular music in his time and elevate him as an important Indigenous artist who was succeeding at a time where there weren’t a lot of Indigenous artists who were playing music that was reaching the top of the charts or playing to arena-sized crowds as Jesse did with Rod Stewart and Faces.

I think aloud about it in the book, and I think about it a lot outside of the book, that Jesse probably didn’t have a lot of people around whom he could bond as a Native artist or who could understand some of the stereotypes that were being exercised on him and so forth. I wanted to elevate him as a Native artist, talk about why it was meaningful that he was an Indigenous artist in his time, and maybe celebrate him as an example that Native people can rally around and maybe young Native kids today who are picking up a guitar and are looking around like, “Well, who’s one of my people that made it, who did this?”

If Jesse can become a musical hero–the character, Jesse Davis, who’s on the albums and the pictures that we see–if he can be a musical inspiration to young Native people today, or any people for that matter, then I felt even more compelled to sort of tell the truth about him, because heroes aren’t perfect people. They need to be fallible. They need to be imperfect in order to be accessible and to be attainable to other people. All of that just further incentivized trying to do a really honest and dynamic account of his story, while also being careful not to push too far in an area that starts to degrade him in some way, and that was challenging.

Douglas K. Miller’s Washita Love Child: The Rise of Indigenous Rock Star Jesse Ed Davis is out this week from Liveright. “Jesse Ed Davis: Natural Anthem” opens to the public at the Bob Dylan Center in Tulsa on Friday, November 15. Details on that exhibit here.