Desperate business owners demand crime solutions from city government: ‘You just feel violated’

11 break-ins in two years. That’s what Heather White has dealt with across her three businesses—Tailleur, Cheval, and Enchante—all on the same block on Main Street in Midtown.

“You just feel violated,” White says as we sit on Tailleur’s patio. “And to have it happen over and over again… it’s just a constant battle.”

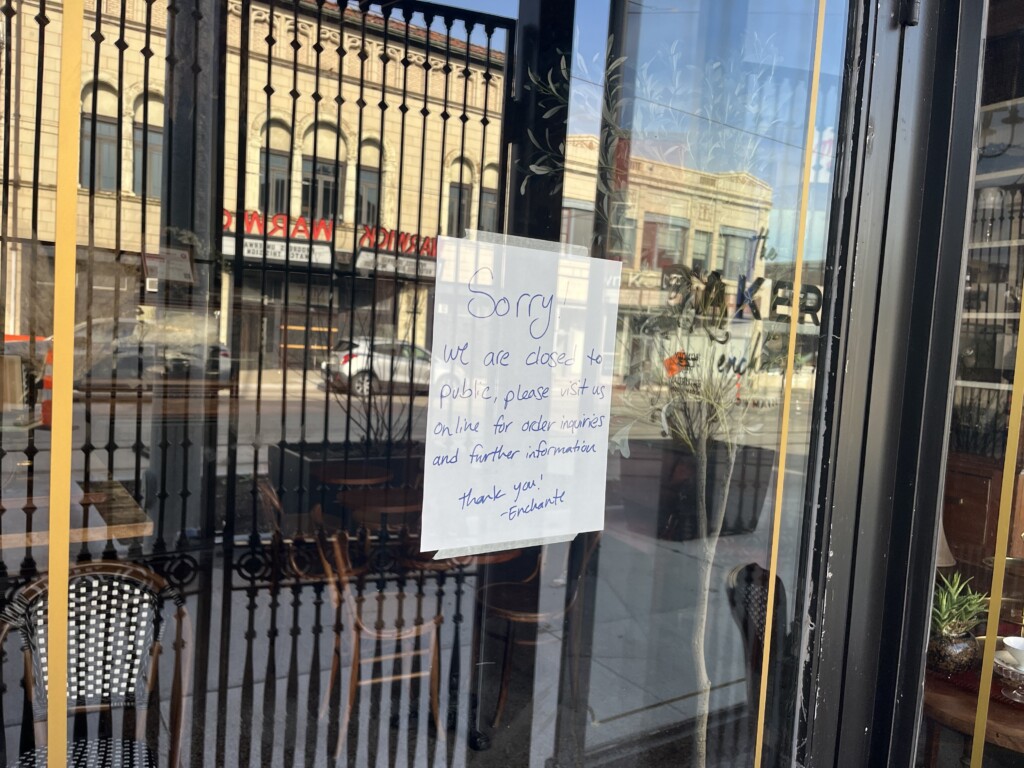

The result? Bakery and cafe Enchante closed its storefront in March. White says the shop also struggled from declining foot traffic resulting from streetcar construction delays (which was supposed to finish this spring). Between declining business, the costs of replacing smashed doors and stolen goods, and fears for her staff’s safety, White says closing the shop’s front of house was her best option.

She isn’t alone. Teocali, a restaurant in Hospital Hill, has been open for 19 years this August. Its owner, Enrique Gutierrez, says he had never experienced a break-in until he got hit twice last year. He says the first time, the thieves walked away with his safe, which held $40,000 he had been saving for renovations.

“The scary part about the second time… everybody had a gun,” Gutierrez says. “I’m getting goosebumps right now, because there are times when I’m down there by myself.”

Two break-ins at Betty Rae’s Ice Cream also resulted in shattered windows and a stolen safe. Cafe Corazon has taken to leaving its cash register empty at night after its break-ins—a tactic that hasn’t dissuaded thieves.

Last September alone, 111 Kansas City businesses were burglarized, according to Kansas City police. And it’s not just small businesses, either. Apartment buildings have also shared the brunt of break-ins, robberies, and vandalism.

Business owners tell me there’s little they feel they can do. Last September, Kansas City announced a Back to Business Fund to aid business owners in vandalism recovery and crime prevention. The program reimburses businesses up to $3,000 in losses and up to $5,000 in security upgrades. Within two months, the city had 109 applications. By December, the City announced it would distribute $70,000 to 30 businesses.

But not just property crimes. Some business owners feel overwhelmed with behavioral issues that cause operation disruptions and make workers feel unsafe.

White describes one man who walked into her bakery and exposed himself to her female staff. Her tip jars would get taken in the middle of the day. Gutierrez shares a story of a man waving a sword outside and angrily demanding a martini in front of guests.

Cait Benedict owns the coffee and wine bar Bisou, which is located near an I-70 underpass that separates the lower West Side with the East Crossroads. She has several pictures of instances around her patio where she says people screamed profanities and accosted her and her guests.

“I’ve lost those customers,” Benedict says. “They’re not coming back.”

Some incidents like these may not be criminal offenses. However, others could be classified under municipal ordinances, such as harassment, disorderly conduct, or public indecency resulting in an arrest.

The Kansas City Police Department’s annual reports do indicate that there has been a modest increase in reports of some crimes against property and society when compared to the years before the pandemic. However, the latest available report is from 2023, so it’s unclear how the issue has changed over the past year.

This all leads to one main question: What does Kansas City do about it?

The past six years

KC’s old jail, the “The Farm” located at 8100 Ozark Road near the Truman Sports Complex, closed in 2009 due to budget constraints. For 10 years, the city maintained an agreement with Jackson County to house detainees in a building next to the county detention facility. That ended almost six years ago in June, 2019.

Since then, the city has been sending offenders more than an hour away to jails in Vernon County and Johnson County.

4th District-at-Large Council member Crispin Rea says the problem with outsourcing jails, in addition to not providing quality facilities, is the lack of control over its operations.

“In my district, back in the summertime, there was a guy who was just terrorizing the neighborhood [where I live],” Rea says. “The guy had a long list of municipal cases out on him, and so, the police department got him in custody.”

Rea says police transported the man to Vernon County, but officials at the jail refused to take him.

“By the next day, he was back in Volker doing the same stuff,” Rea says. “That doesn’t happen if we control our own facility.”

KC police could not verify this incident. Sherae Honeycutt, Kansas City’s press secretary, confirms that “the city does not have authority over which individuals are accepted by contracted jail facilities. Jails have the discretion to refuse custody of a detainee.”

All that has led to a situation where police have limited options after making an arrest.

“I was on a ride-along and saw a stolen car recovered by police right off Independence Avenue,” 1st District Councilmember Nathan Willett says. “There was a crew of five people in there, and [the officers] were like, ‘We’ll only be able to take the driver and the rest can go’ because that’s all they have space for.”

Data from a jail study dated April 18, 2024 shows a sharp decline in police arrests after 2019. That includes the rate of arrests per officer, which have been nearly cut in half. The study suggests a lack of jail has been a primary factor in these declines.

Police have also been operating at a staffing deficit. As of Feb. 1, the department was short 244 officers and 77 professional staff members, according to Sergeant Phil DiMartino. That shortage is a little smaller than it was in November, and DiMartino says the department is “trending in the right direction” with a big new academy class and new call-taker and dispatcher training.

KCPD also added a new foot beat last fall to increase police visibility downtown during the day. But the beat equates to four additional officers and a sergeant in charge of the entire downtown (from the River Market to the Crossroads and the West Bottoms).

Even so, people may feel emboldened to commit crimes even with police present. On April 12, an ATV driver ran over a police officer downtown, causing head injuries before fleeing the scene. Mayor Quinton Lucas posted on X that the city would pursue serious enforcement action and apprehension “for all those causing fear, serious injuries, and harm even to themselves on the streets of Kansas City.”

Meanwhile, many of the issues at businesses and residential properties happen over night and in regions like Midtown and beyond.

Kansas Citians vote for tax to fund jail

On April 8, Kansas City voters approved the extension of a 20-year, quarter-cent sales tax to fund public safety and law enforcement initiatives, including the building of a new city jail, which the city estimates will cost $250 million. The vote was 60 percent to 40 percent.

Proponents of a new jail argued that the 105 beds the city contracts with Vernon and Johnson counties aren’t enough. A recent investigative report from KSHB 41 found more than 400 Municipal Court prisoners were released early over the past four years due to capacity issues. 84 releases were against a judge’s orders, “which often means a judge ruled that person ‘a danger to him or herself or others,’” the report stated.

6th District Council member Jonathan Duncan opposed funding a new jail. He says a city jail would not address Kansas City’s most pressing crime issues.

“I hear stories about armed gunmen who steal our cars, serial burglars who damage our homes and wreak havoc on our small businesses, and persistent gun violence which continues to plague our streets,” Duncan says. “A city jail cannot solve any of these issues because all of these are state crimes.”

According to Jackson County Prosecutor Melesa Johnson, property crimes, car thefts, and break-ins can all range from municipal to county and state crimes, depending on the circumstances of the incident.

“It all depends on the facts and available evidence,” Johnson, who is a proponent of a new city jail, tells me. “A municipal jail would fill a critical gap in our criminal justice system by providing meaningful consequences for misdemeanor offenders, intervening before they potentially begin committing felonies and more serious crimes requiring state prosecution.”

Council member Rea agrees that the more high-level crimes should be prosecuted as state offenses. But in his experience, “there are pretty significant gray areas.” He says there’s a gap that “leaves a pretty high number of other criminal activity… falling through the cracks.”

Duncan, who says he was on the Municipal Detention and Rehabilitation committee, says they found “most of the people who go through our jail system are jailed on charges of public urination, sleeping outdoors, trespassing, and small theft.” He claims the jail will be an “expensive Band-aid” for the real issues of homelessness and mental illness.

Organizations advocating against the city jail include Decarcerate KC and KC Tenants. The Kansas City Defender is an independent publication that has also been critical of the detention center. None of these organizations responded to questions before the vote.

However, Decarcerate KC released a statement after the vote, stating: “Tuesday’s results are not what we had hoped for… These results reflect our elected officials’ unwavering commitment to ignoring the glaring quality of life issues facing their constituents and playing into existing anxieties around crime in Kansas City.”

Issues that, as Decarcerate KC stated, include increasing costs of food and rent as well as access to mental health resources.

“We know our communities deserve real investments, not punishment. Our understanding has been sharpened and unchanged—New jails do not make us safer, and there are countless alternatives to incarceration that can bring us closer to safer communities where people’s needs are met.”

An alternative to incarceration

Council member Duncan says he would rather see city tax dollars going toward alternatives to incarceration, addressing the root causes of crime. He says these include poverty, education, affordable housing, health care, and mental health care.

Duncan, along with Council member Rea, passed a resolution directing the city manager to seek a design proposal for a new Community Resource Center, which would address some of these issues. There is no funding yet allocated for this project, and after Brian Platt was recently fired as city manager, former deputy city manager Kimiko Black Gilmore has been serving as interim.

Despite efforts to increase community services, Rea says there are “situations where people are resource-resistant and there’s a nexus of violent behavior.” In those cases, he says a jail is needed.

Duncan says police stations have holding cells that should be utilized more. According to KCPD Sergeant Phil DiMartino, side station jails are limited in capacity and were only designed to hold people for four hours.

Duncan also pointed out that the city already allocated $16 million to create 144 beds at the KCPD headquarters on the eighth floor of the downtown courthouse. The ordinance states these beds will be designed for stays up to 24 hours, with a maximum holding of three days. Construction should have begun earlier this year, according to the ordinance, and operation is supposed to begin in 2026. Honeycutt confirmed construction has not yet commenced.

Rea says the proposed municipal jail would be better equipped than the KCPD headquarters to aid rehabilitation efforts in order to curb recidivism.

“I’d love to imagine a world where we don’t have jails and detention and incarceration,” Rea says.

Despite the vote, community groups vow to keep fighting against incarceration.

“Renewing the tax does not make a new jail inevitable,” Decarcerate KC stated. “Though the vote is over, the fight against the city jail goes on.”

Processing crime in KC

Processing even a single crime takes an extraordinary amount of time and effort from the victims, police, and prosecutors. In cases where people committing felonies are caught in the act, the wheels of justice might turn a little quicker. But in most situations, like when petty crimes are committed by people covered in dark clothing and masks, the burden of finding a solution—often in the midst of repeated offenses—can be enough to break a business’s back.

“I’m in the hole,” Gutierrez says of Teocali’s finances.

White and Gutierrez painted similar pictures of what the experience is like: You arrive at your property and find a gaping hole, broken glass everywhere. Your money and maybe your register is gone. Some of your products are missing. If you’ve had the means to install cameras, you check the footage, which probably doesn’t help much: You get a timestamp, a vague depiction, and a better idea of how they committed the crime.

You force yourself to stay calm as you call the police. You report your incident in as many details as you can. You’re assigned a case number. You contact your employees and publicly announce you’re closed for the day. A detective comes out to meet with you. You spend the morning cleaning up glass and taking further inventory of the damages. Then what?

For Gutierrez and White, it was always just back to business.

“It’s just built into the business models that we’re going to have, what, $100,000 in losses this year,” Council member Willett says.

Gutierrez and Benedict think it would help to see more police on the streets interacting with the city’s residents and business owners to instill a sense of safety. Prosecutor Johnson and Sergeant DiMartino also stress working toward better relationships between law enforcement and the community. And proponents of the new municipal jail acknowledged that a local detention facility isn’t a cure-all.

“There’s multiple layers to the onion,” Benedict says. “It’s getting into the home when they’re young… and then there is the mental health—We need a mental health facility, and then we need a jail.”

Proponents and opponents agree that crime prevention is key. However, proponents—including Rea, Willett, and Benedict—believe the threat of jail time could be enough to dissuade some potential criminals and reduce the overall amount of crime.

“There needs to be consequences for actions,” Willett says.

Action today for less crime tomorrow

All of these solutions are long-term fixes. No one has a magic wand that can fix the city’s woes today. Steps taken today may only provide results in the years to come.

But Willett urges expediency on decisions that can be made now, “especially with the World Cup coming,” he says.

As for the businesses dealing with the issues every day, Heather White says it’s enough to make her want to quit.

“That’s one of the things that always goes through your mind… ‘Should I just sell it? Should I do something else with my time?’”

Yet, she pushes on. Part of her reason is the staff she employs, which she says numbers more than 50 people between her businesses. She says they haven’t given up on her, so she doesn’t want to give up on them.

Another part of it is her love for what she’s created. And what she’s still helping to create.

“There’s a new cafe going in there,” she says of the Enchante storefront. She says she’s working with a new partner, Austin Morris, who was a previous regular.

Morris announced on Instagram he will rename the cafe Soli Deo—Coffee & Bakery. While Morris takes over owning the cafe part of the shop, White will continue her bakery in the back.

“He has a whole team coming in… to focus and concentrate on it being more of a safer coffee shop,” White says.

That team will be put to test when Soli Deo opens to the public Saturday, April 19.