Christian sober living homes expand in rural Missouri largely without state oversight, funding

The facilities have emerged in a part of the state where treatment and services for people battling substance use disorders are scarce.

Dayton Austin, Jayson Jackson, Ronnie Baum, Jeffrey Dunbar and Clarence Stephenson gather in the living room of Big Boy Men’s Ministry, a faith-based sober living house in Cabool on Oct. 28 (Steph Quinn/Missouri Independent)

Jerry Chiasson had been living under a bridge in Gainesville, fighting larceny charges and trying to get clean.

Biking from Springfield to Mountain Home, Arkansas, where he’d planned to stay with a friend, Chiasson, 52, was pulled over and arrested on a warrant for a stolen car — charges that were eventually dropped.

While fighting the charges, Chiasson said, he got into a cycle of “using, stressing,” failing drug tests at his court appearances and then “hav[ing] to go do seven days in jail.”

He was in jail when another inmate told him about the Action Recovery Center, a Christian sober living house in Gainesville. The residential program promised to help residents with substance use disorders find stability through faith, work and peer support.

Chiasson became one of about 20 Missourians who have graduated from Action Recovery Center’s nine-month program since it opened in November 2023. It’s one of a spate of faith-based sober living houses established by Christians in recovery from substance use disorders in Wright, Ozark, Douglas and Texas counties.

They’ve emerged outside Missouri’s regulatory structures for recovery houses in a part of the state where treatment and services for people battling substance use disorders are scarce. There are 3,677 accredited beds in the state, and 44% of them are located in St. Louis or Kansas City. There are no accredited beds in Ozark County, where Action Recovery Center is located.

While these unaccredited recovery houses meet a need in communities where treatment options are limited or nonexistent, they raise concerns that a lack of any oversight could hinder their effectiveness or lead to abuse.

“These things are popping up all over,” said Judge Craig Carter, presiding judge in the 44th circuit, which spans Ozark, Wright and Douglas counties. “And they give a lot of people who otherwise could not get it, they give them a second chance.”

Carter said that while he has a working relationship with recovery houses like Action Recovery Center and Mountain Moving Ministry in Wright County, he doesn’t always know what to expect from new houses farther afield.

“If I send someone all the way down to Butler County, I need to know that they’re going to communicate with me and that they’re above board,” Carter said.

Recovery houses in Missouri are not required to undergo any certification process to open their doors. But in order to receive state or federal funding disbursed by the Missouri Department of Mental Health, they must be accredited by the Missouri Coalition of Recovery Support Providers.

The coalition accredits recovery houses using standards established by the National Alliance of Recovery Residences. The standards cover residents’ rights, building safety and the houses’ relationship with neighbors, and after initial accreditation, the coalition visits houses every two years to ensure they still meet all requirements.

Merna Eppick, director of the coalition’s housing committee, said the aim of accreditation is to strengthen support for residents of these recovery houses.

“We try hard to help you become better,” Eppick said. “Our goal is, even if you’ve got 20 deficiencies, you’ve got 90 days to fix it. We revisit it and say, ‘Yay, you did a great job. You’re accredited.’ We want to help all of us be better.”

But Action Recovery Center — and a handful of other recovery houses in southern Missouri — are not seeking accreditation.

Ken Polm, founder of Big Boy Men’s Ministry in Cabool, said he doesn’t pursue state funding because he is concerned the money would come with requirements that could sideline residents’ spiritual development.

“If we receive state funding,” Polm said, “a lot of times, we’re not allowed to make it all about Christ. We get limited to what we can actually do, as far as the type of classes.”

For Polm, the biggest issue with accreditation relates to medication-assisted treatment. He and other leaders of faith-based sober living homes told The Independent that they worry taking medications like methadone or buprenorphine to beat an opioid addiction sets people up to relapse.

Decades of research have shown that methadone and buprenorphine taken as “maintenance” medications, for months or years, sharply reduce overdose deaths by 50 to 70%.

Recovery houses don’t have to accept medication-assisted treatment to be accredited or receive state funding. But they do if they want any federal funds through the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

To fish for a man

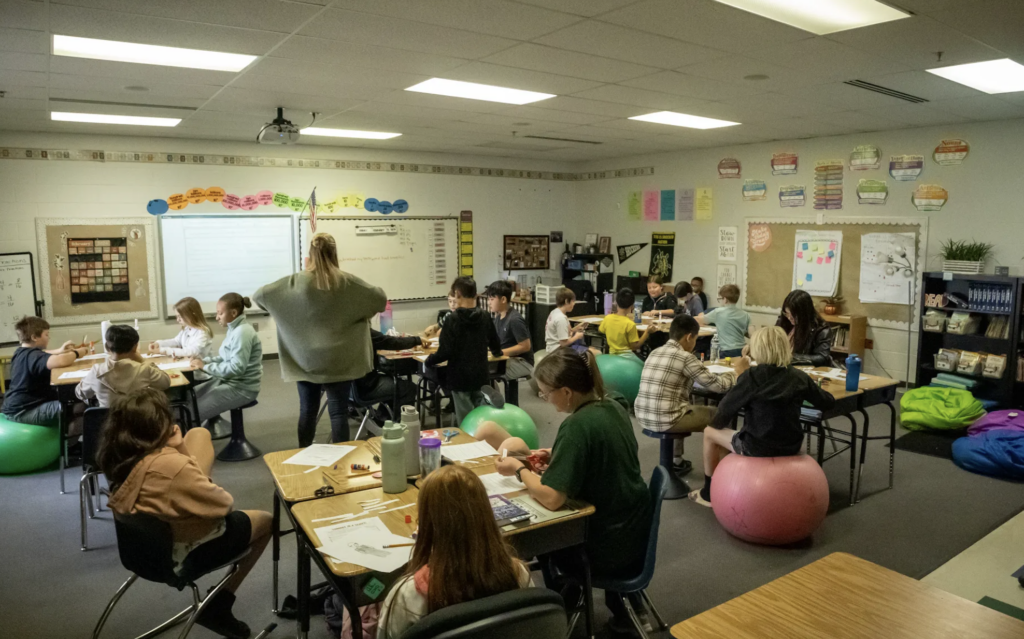

On a Tuesday evening in late October, 15 to 20 men spill from the living room to the kitchen of an old house in Cabool, with a couple of people poring over Bibles in an adjoining room.

It’s one of two homes to Big Boy Men’s Ministry.

There are at least four bedrooms filled with the stuff of the men’s lives: family photos taped to the wall, backpacks, laundry hampers clustered around bunk beds set up dorm-style. Polm is rushing to get to a revival, and he’s trying to round up residents who want to come. Others stay to socialize, with hugs and gentle ribbing among men who have become brothers.

Polm said he began his ministry to men struggling with addiction while he was on probation. He’d strike up conversations when he reported to the probation office.

“Just through conversation, you could tell that they were trying to have a new life, but they didn’t know how to have it,” Polm said. “So I would basically start there. Then after that, even when it wasn’t my visit to see the probation officer, I would still attend the office, just to go in there and sit and fish for a man.”

Polm said he and his wife, April, were “blessed…with a very big house.” So they started welcoming men to live in their 3,200-square-foot basement. Big Boy Men’s Ministry now spans two houses, and April started a recovery housing ministry for women called Abundant Grace.

“Me and my wife, we really enjoy it,” Polm said. “Because downstairs, when the guys are down there and they’re being rowdy, laughing and just carrying on with each other, being brothers with one another…being able to be partakers of that experience is so rewarding.”

The men work during the day and attend evening classes four to five times a week. Saturday is laundry and shopping day, Polm said, and from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m., they volunteer in the community, building decks, repairing roofs, washing windows, cleaning gutters, “just all kinds of stuff.”

Once a month, the men hold “street church” and share their testimony with the public.

“Either myself or the other men from the ministry that’s been raised up from discipleship to be preachers, they get to be up there preaching the word of God, and we do altar calls,” Polm said. “So we’re very involved on the weekends in our community.”

The men pay $150 per week after their first two weeks, and the ministry accepts donations.

In late October, there were around 20 men in each of the Polms’ houses. Polm said 50 to 60 men graduate from the ministry each year, and that he and his wife counsel residents like parents.

“I sit them down as men, and I have these hard talks with them like a father would give them, and I give them the best advice that I can come up with,” he said. “And my wife does the same thing. It’s pretty fascinating and such a joy to experience this, that some of the men will even come to my wife and say, ‘Hey Mom, can we talk?’ They’re having wife problems, or they’re having children problems.”

Dayton Austin, 28, of West Plains, said Polm has been talking to him “man to man” since the first time he got in trouble in 2019, even when he slipped up.

He did his first recovery housing program at Mountain Moving Ministry in Mountain Grove, Austin said, where Polm is board president.

He graduated from the program and “made all the right moves, did all the right hoops, said all the right words,” but got another charge within six months.

Austin kept graduating from recovery housing programs and getting in trouble, he said, selling fentanyl and “just being crazy.” He had periods of success, too, studying for a few years to be an occupational therapy assistant in Springfield.

“I was doing the thing, without people having to tell me what to do,” Austin said.

He loved his studies, he said, but they were stressful and he returned to old patterns. He got caught with meth and a gun.

Polm told him to just show up at Big Boy Men’s Ministry.

“I had a feeling I was destined for prison,” Austin said, “but I knew I needed to be here before I went.”

Five months into his stay, Austin was sent to prison for eight months. But, he said, “I had a foundation to go to prison on now.”

After his release this year, Austin returned to Cabool.

He looks up to the ministry’s growing group of graduates. Some of them have become part of the ministry’s leadership.

“All these guys are on the board now, that God’s really using,” Austin said. “He gave them businesses. They’re busting with kids. They’re busting with families. … They’re creating their own ministries.”

Austin, who is now a certified nursing assistant, said he hopes for a family of his own someday.

“It’s all a process,” he said, “but I know what I want.”

Grassroots standards

It’s a busy November morning at the Wright County Courthouse in Hartville, with almost 70 people on the criminal docket.

Chris Turner, 48, of West Plains, is the first to be called before the judge.

Turner, who was found guilty of burglary and meth possession in April, was called to court for a probation violation hearing because she hadn’t been making her restitution payments. But she was able to satisfy Judge Craig Carter that she’s making progress.

She’s settled up with the county. And in June she moved into a Christian sober living house in West Plains called Design Your Life.

The women’s recovery house was established in September 2024. Carter said he had never heard of it.

“I can honestly say it’s the best thing that’s happened to me since I got in trouble,” Turner told The Independent.

Before she joined Design Your Life, Turner said she was facing homelessness and struggling to find transportation to her drug tests. She said she used to walk the 43 miles from West Plains to Mountain Grove.

Now she gets transportation to court and her job at a sawmill from Design Your Life. And living in a house full of women is coaxing her out of her shell, she said.

Carter said he is a strong supporter of Christian sober living houses.

But he said there’s a need for shared expectations between sober living houses and the courts when completion of a recovery housing program is a condition of a defendant’s bond or probation. He said communication and fair, consistent drug testing are two of the most important areas for agreement.

Judges can’t unilaterally force a defendant to participate in a religious program, Carter said. But if a defendant applies to a Christian sober living house and is accepted, it can help make the case against keeping them in jail or sending them to prison.

“We’ve sent people to some of the ones in Springfield,” Carter said, “and guys will run, and they won’t let us know. We’ll have them back on the docket in two months. Where is this person?”

Wright County Prosecutor John Tyrrell said he is concerned a lack of standardization can allow abuse of residents.

He gave the example of Compassion House in Niangua. The facility’s founder, Isaac Tilden, was charged this year with child abuse and forced labor. The complaints allege that Tilden compelled residents to work for free or face revocation of probation or parole, and that he failed to protect his daughter from sexual abuse by residents.

Accreditation provides standards and protections for recovery house residents, but accredited recovery beds are scarce in some parts of the state.

Shawn Wilkerson, who is spearheading plans to expand Mountain Moving Ministry to Ava, said he and a friend spent 10 hours trying to find a spot for him in treatment when he embarked on his recovery journey five years ago.

“The guy said, ‘Well, it going to be a year,” Wilkerson said. “I said, ‘Well, in a year I’ll either be in prison or dead.”

Howell County, where Turner and Austin are from, has only 18 of the state’s 3,677 accredited recovery beds. Texas County, where Polm runs his two recovery houses, has one accredited house with 22 beds.

Springfield and Branson have a combined 641 beds, but each is over an hour away from Gainesville or Mountain Grove. And transportation is a challenge in this rural part of the state.

Sober living houses typically transport residents to and from work and court.

“Twenty guys in a house, and they all have different court dates,” Carter said. “And in different counties…. They just drive the tires off.”

Tyrrell said he’s leery of state oversight but suggested that judges, prosecutors and attorneys gather on a circuit level to set expectations for recovery houses.

“I need to know that the programs understand that these are court orders, and court orders have to be complied with,” Tyrrell said.

Wilkerson said leaders of the residences and the courts should work locally to share best practices.

“We need to build — and I think this is where we’re at working on it — building a baseline portfolio to where I could sit down with a prosecutor in Greene County, open up a portfolio and say, ‘This is what we do, why we do it, how we do it,” Wilkerson said.

Tyrrell said the recovery houses the court works with often share information that helps him make decisions about defendants’ cases.

“I can go talk to the director,” Tyrrell said, “and say, ‘Hey, tell me about this person. What’s he like? Is there something I need to know?’ And they’ll be honest with you. That helps.”

Jayson Jackson, 27, said he was about to be sent to prison for 10 years after absconding from probation when he told the prosecuting attorney on his case that he was going to Big Boy Men’s Ministry. Because the prosecutor and judge were familiar with Polm’s recovery house, they agreed to give him a chance.

“I go, ‘God sent me a piece of paper telling me I’m going to Big Boy,” Jackson said. “So unless you [or that judge] have got more authority than God, I know I’m not [going to prison].”

Jackson said he had been trying to break into an abandoned house in Willow Springs while on the lam when he encountered God. He had fallen to his knees on the side of a road and prayed. Then, he said, a piece of paper hit him in the face.

It was an advertisement for a new sandwich from Dairy Queen, Jackson said. On the other side, someone had written down Polm’s phone number.

Jackson said he’s been sober for 3 years. Now he travels around the state with Polm, preaching, and he works at a sawmill.

“I throw logs for a living,” Jackson said. “They come in, roll them down the log deck, chop them all up and I stack them.”

Jackson said the hard work has been worth it.

“It’s cold, and it’s wet,” he said. “But I wouldn’t trade the life that I live right now for the whole world.”

Missouri Independent is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Missouri Independent maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Jason Hancock for questions: info@missouriindependent.com.