Central Standard Theatre’s Invasion imports some must-see works

The Invasion — Central Standard Theatre’s annual international festival — is starting to wind down, with Fringe Festival about to open. But there are some winning shows among these collaborations from England, Northern Ireland, Canada, France and the United States. Three of the six are reprises, so audiences have a second chance to see performances that can be inventive, smart, moving, funny or simply diverting. And this year, the event is using two venues: Metropolitan Ensemble Theatre (3614 Main) and MCC-Penn Valley (31st Street and Southwest Trafficway). Details here or by calling 816-569-3226.

We saw five of the shows, and they reminded us why we value the Invasion’s return each year.

It’s tough to find a sunny side of suicide, but Irish comedian Nuala McKeever comes close. Her one-woman show, In the Window, handles love and loneliness with a light hand.

The show opens on a woman named Margaret as she shuffles through her home in fuzzy pink slippers and cocktail attire. She fusses over her appearance, her living room, whether to light a lamp. She’s not planning a party — she’s staging her suicide.

Before she can chase a candy dish of shocking-pink pills with her fifth glass of rosé, a young man named Chris — a burglar, she assumes — climbs through her window. Then a loathsome relative barges through the door. Then a handsome policeman knocks.

McKeever deftly inhabits each character, heightening the show’s frenetic energy as she flits from subject to subject. She’s so convincing that the small set starts to feel crowded. But her greatest feat as a performer is investing us in Margaret’s bare ambition. Over the course of the 70-minute show, her demeanor gradually shifts from one of brittle disappointment to bright-eyed, heart-sick hope.

As the script rolls on, however, plausibility buckles under the weight of one too many plot twists. The show’s climax comes on the heels of an eye-rolling theatrical gimmick, cheapening an otherwise nuanced character sketch. Still, McKeever’s gentle humor and poignant portrayal make In the Window worth the view.

Moments before ARCOS Dance’s multimedia The Warriors: A Love Story began, a stranger told me about the terrorist attack in Nice. I entered the theater anxious and afraid. I staggered out hopeful, thanks to ARCOS’s captivating blend of modern dance, historical footage and love-softened memory.

With kaleidoscopic shards of narrative, filmmaker Eliot Gray Fisher narrates the (true) story of his grandparents’ meeting and courtship during World War II. Glenn was an American soldier with a doctorate in philosophy; Ursula was a German dancer who survived the firebombing of Dresden.

Fisher drives scene changes by plucking objects from his grandmother’s trunk. Along the way, ARCOS’s athletic dancers alternately illustrate and interact with audio recordings of the couple, projected quotes from Glenn’s war journals, period film clips, and original animations with the moody gestures of cave paintings.

Lush orchestral compositions — some prerecorded, some performed live by Fisher on a keyboard — unify the fragments into a dazzling, prismatic whole. If the show errs, it does so simply by playing one note too many. A sequence with a hand-cranked air-raid siren stretches on too long, the dancers repeating old themes instead of teasing out new. And the show’s opening image — Plato’s allegory of the cave — never quite returns to weigh on Fisher or his grandparents’ experience.

Still, Warriors is an Invasion must-see, simultaneously original, affecting and humane — exactly the kind of show we need right now.

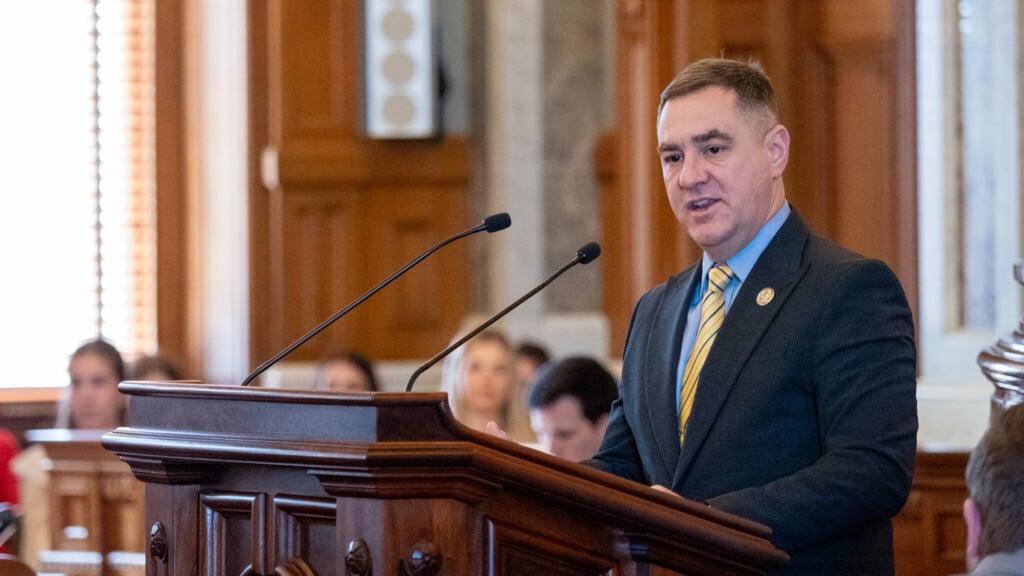

Hamlet (the Notes) may sound like a graduate seminar or some erudite work, but it’s really an exercise in pure entertainment. In this cleverly composed one-man play, John Fitzgerald Jay (above) is mesmerizing as a director trying to get a very unwieldy production of Hamlet in shape. He has a lot of work to do. The show is running five hours and 35 minutes “with no interval,” he says. One solution: cutting “To be or not to be.”

As he advises his actors to only gradually bring down the fourth wall, he immediately pierces it himself, addressing audience members as fill-ins for his cast and technical designers. (The fourth row is fairly safe for those who want distance, except you really don’t.) “Go to page 7 in the Pelican version,” he says, or “page 150 in the Arden.”

As he works to get inside Hamlet’s head and to motivate and mentor his actors, he continually complains about missed technical cues. An aside to a lighting tech: “Here’s a word you understand: dim.” The play’s the thing, he tries to remind them all, “a shitshow of manipulations.” Fitzgerald is like Hamlet giving notes to the Players, weaving in pop-culture and current references, physical theater and a whole lot of humor as he also makes genuine, often moving connections to the original work.

Familiarity with the characters and plot of Hamlet, while not a prerequisite, will certainly enhance the experience. “Theater of distortion,” he calls this production, and he makes you think that’s a thing. It isn’t Hamlet in any traditional sense, yet it reflects on that play’s tragic figure in a way you wouldn’t imagine. Hamlet (the Notes) plays through Thursday, July 21, so hurry.

Was William Shakespeare merely a frontman for the real playwright? In the one-man Your Bard, Nicholas Collett (below) argues for the other side in a fresh, unusual take on the subject that ignores the fourth wall completely.

Emerging first as a slightly flustered, fuddy-duddy college professor, he sets the stage, quickly reviewing the “usual suspects” for Shakespeare’s true identity. (His book, he tells us, is Shakespeare Who?) He then leaves the stage (and the audience exits the theater), but the show isn’t over. He returns minutes later as the man himself, for a very personal debunking of those frontman theories. And Shakespeare’s missing years? He fills those in as well.

You’ve probably never envisioned the person of Shakespeare quite like this. The charismatic Collett commands the room in a truly intimate, funny and energetic performance that wraps us up in Shakespeare’s life and person. (The topic of the plays’ authorship seems particularly timely, given the recent exhibit of Shakespeare’s First Folio at KC’s Central Library and a talk there by local theater scholar Felicia Londré on the Edward de Vere theory.) Collett, who gave a compelling performance last year in Nelson: A Sailor’s Story and who made a lasting impression as a World War II pilot in Spitfire Solo the year before that, is Your Bard through Wednesday, July 20, at MET. Go and enjoy.

Escape From the Planet of the Day That Time Forgot is a title as zany as the story that unfolds: A reclusive scientist, his attractive female ward and his devoted laboratory assistant time-travel on a rocket — before there was such a thing — to planets unknown. Gavin Robertson, who so memorably mimed Bond! An Unauthorised Parody (and, last year, Crusoe: No Man Is an Island), and his talented co-stars, Simon Nader and Katharine Hurst, spoof science-fiction B-movies — The Day of the Triffids, The Time Machine, etc. — through their consummate collective skill in physical theater and mime.

Those who saw Robertson re-enact a Bond-style car chase using toy cars will have an idea what these performers can do with an ironing board (I‘ll never see mine the same way), a handheld vacuum, a sheet of plastic and a pile of boxes, as they traverse the universe, confront carnivorous plants and meet Norse gods while gathering scientific samples and doing research. There’s plenty of tongue-in-cheek dialogue, too. The jokes are self-referential, sometimes subtle and other times broad, with nods to B-movies, sex and women’s rights. The ward, Helen, who’s brought along to do the screaming, we’re told, will be too busy with housework to help with the science, even if she’s the brightest of the bunch. “She’ll be wanting equal pay next,” her uncle moans, then laughs.

The show drags a bit as it nears its end, and those unfamiliar with the movies spoofed may be lost in space at times. But it’s also just fun — an understated marvel of movement and prop manipulation and British wit. It’s onstage at MCC-Penn Valley through Thursday, July 21.