Canary in the corner booth: What restaurant closures reveal about the KC economy

Some legacy restaurants close ahead of World Cup opportunity while others report strong sales. Who can afford a night out reveals a split economy.

Happy Gillis Cafe & Hangout closed in Columbus Park this year. A new restaurant is planned to open in the space in 2026. (Thomas White/The Beacon)

The economy has developed a split personality.

Stock prices are near record levels. Some tech companies, particularly in the AI space, are being valued at staggering numbers, fueling a rush to develop data centers.

Meanwhile, half of workers are struggling to get by and lines for food assistance block traffic.

The mixed signals can get confusing. But if you really want to know what’s going on, here’s a tip — ask a bartender.

Restaurant and hospitality workers have a front-row view of our current mixed or “K-shaped” economy — where the top is booming while the rest are scrimping.

“People are spending their money either carelessly or more carefully,” longtime bartender Perla Jacobo told The Beacon. “It’s honestly one of the two. They’re either endlessly consuming or being really intentional about how much they’re spending.”

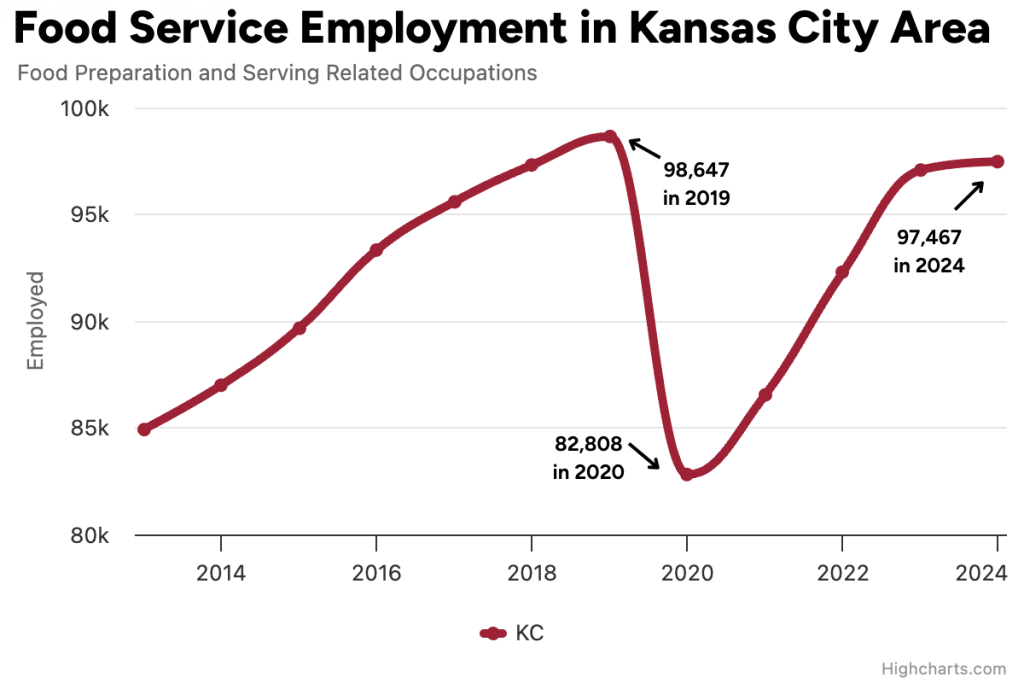

Clocking in at almost 100,000 workers, the restaurant industry is the third-largest occupational group in the Kansas City area. These workers see who has discretionary money to spend and how many people are walking through the door. Since the industry is also notoriously fickle, they feel economic shifts before almost anyone else.

“I think we are a good bellwether,” Mike Burris, executive director of the Greater Kansas City Restaurant Association, said about restaurants in the broader economy.

For example, restaurant workers felt the economic effects of the COVID pandemic first and the industry is still dealing with a lagging local recovery, which mirrors broader regional trends. While everyone is dealing with higher food prices, your favorite brunch spot knew about that run on eggs before everyone except the chickens. Likewise, rising rents rank among the most common reasons restaurants close.

With that in mind, it sets off alarm bells as we see several area restaurants and bars close this year, especially ahead of the always-busy holiday season and a promised boom from the World Cup. But the answer to why that’s happening — just like the economy at large — is complicated.

The closures

Recent closures read like a who’s who in the Kansas City hospitality scene.

- Corvino Supper Club is closing after nearly eight years.

- Afterword Tavern & Shelves is closing after seven years but looking for a new home.

- D’Bronx closed its last location after 35 years in the area.

- Brio Italian Grille, Chuy’s and Seasons 52 all shuttered this year as part of a wave of “strategic closures” by the new owners of the Country Club Plaza.

- Waldo Thai changed ownership after seven years of operation and closed indefinitely two months ago.

- Gilhouly’s dive bar closed after 29 years.

- Plate Restaurant Group went from expansion plans to filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy to reorganize this year (and remains in operation).

- Happy Gillis closed after 17 years. New owners plan to open a different restaurant in the space next year.

- Bar K closed despite a regional expansion after nearly a decade.

- Homesteader Cafe closed after 10 years.

- Danny Edwards Blvd. BBQ closed after 18 years in the location.

Each of these restaurants and bars closed or filed bankruptcy this year for its own unique combination of reasons. Some stated explanations for closing include lease disputes, rising costs, personal decisions, lower alcohol sales and dwindling foot traffic.

“There have been a few of them here (closed restaurants) that I’ve been surprised about,” Burris said. “About a third of most restaurants’ income is in the last two months of the year… If they feel like they aren’t seeing or going to see those sales increases, then there’s no reason for them to stay open longer.”

Burris says that there is a natural churn in openings and closings, and that despite the closings he sees the area’s restaurant industry as generally healthy.

The National Restaurant Association — which is made up of groups like Burris’ Greater Kansas City Restaurant Association — published a survey in late November showing that 48% of restaurant operators reported higher same-store sales in October than a year earlier.

But what complicates things is that the same survey reported that 35% said sales were down and 48% reported lower customer traffic in October when compared to last year. A plurality of operators have reported reduced same-store foot traffic nearly every month this year.

Generally, sales are up or the same but fewer people are going into restaurants. That’s a street-level indicator of the K-shaped economy at work.

What is a K-shaped economy?

Jacob Brewer is the general manager of Noka, a Japanese restaurant in Martini Corner. He says business has been great. Noka’s checks typically average $50-$100 a person, according to reviews, and Brewer said they routinely fill and turn the 88-seat restaurant.

He sees signs of distress in the larger economy — ticking off tariffs, rising food costs and overall inflation — even as Noka’s sales are significantly up year over year. This confuses him.

“I see videos of people waiting in food lines and then I see a full restaurant going on a wait every single weekend,” Brewer said. “It’s such a weird dynamic because I keep thinking people are going to stop eating out because they can’t afford it, but I’m just not seeing it here.”

Brewer isn’t wrong to be confounded. The economic data supports both realities existing simultaneously. Economists have dubbed it the “K-shaped” economy.

The term was popularized by William & Mary economics professor Peter Atwater. He told the Associated Press this month that inflation has hurt households that make less than $100,000 while asset inflation has helped those with wealth.

The result is a “K” where there are gains at the top, decline for the bottom and a shrinking middle. In recent years and especially since the COVID pandemic, the top income earners have largely driven economic gains while the bottom two-thirds have struggled with rising costs.

“For the last five to seven years, the economy has been driven almost entirely by people in the upper third of income earners,” Chris Kuehl, an economist who co-founded Armada Corporate Intelligence, told The Beacon in August.

This trend shows up in your favorite restaurant.

A September report from the National Restaurant Association said that nearly $6 out of every $10 spent in restaurants come from households that make more than $100,000, based on 2023 data. Meanwhile 44% of lower-income Americans making roughly less than $50,000 a year say they are eating out less this year compared to 2024, according to a YouGov survey.

Jacobo confirmed seeing a lower volume of overall restaurant and bar guests in recent years. In the spaces where she’s worked since the COVID pandemic, she’s seeing a mix of higher-end clientele and people out for a special occasion but fewer blue-collar regulars.

The Beacon spoke to several front-line restaurant workers who weren’t comfortable speaking publicly for fear of losing their jobs or hurting the reputation of the establishment where they work. One bartender in Lee’s Summit shared that foot traffic was down 25% and that take-home pay is also down as a result.

“There’s definitely a tale of two cities going on here,” he said. “The wealthy are still coming out spending big. I see them more than the average Joe coming in after a hard day of work.”

‘Shrinking market’

Forbes Cross spent nearly 50 years in the Kansas City restaurant business, owning 14 establishments before retiring and closing Brookside’s Michael Forbes Grille in 2024. He’s seen trends come and go.

He said this feels different.

The Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City’s Beige Book said that consumer spending is weakening as foot traffic and leisure activities have slowed. The local Fed cites a softening labor market paired with the recent government shutdown among the reasons.

“The markets just shrank,” Cross said about the restaurant industry after COVID. “That upper-middle class on down — I think they’re staying home more.”

He described a calculus that’s become familiar to anyone watching their bank account. A nice dinner out with a bottle of wine can easily run $150 to $200. The same meal at home costs roughly $50 to $75.

Fewer people in the door means fewer workers are needed.

Frank Lenk, the Mid-America Regional Council’s director of economic research, said the Kansas City area is in a “jobcession,” meaning growth hasn’t stopped entirely, but it’s low enough that unemployment keeps ticking upward.

The restaurant industry locally has only recovered to 85.9% of its pre-pandemic level, according to Lenk’s local economic outlook. Lenk also projected accommodation and food services — the sector that includes restaurants — to be down 1,541 jobs in 2025.

“It’s just economics,” Cross said. “People just can’t afford to eat out as much as they used to.”

Public opinion backs him up.

A 2024 survey from Vericast found that 68% of consumers are “trading down” from restaurant meals to cooking at home. A 2025 YouGov survey said that two-thirds of diners who dine out less frequently cite increasing prices as the reason.

Burris is quick to point out higher food prices — up 29% overall since 2020 — rose across the board, so it’s more expensive both at restaurants and grocery stores. But most restaurants use a pricing strategy where food costs are targeted to be 30% of the listed menu price for customers. This is to account for the other two large costs for restaurant operators: labor and fixed overhead.

Restaurant challenges mirror broader challenges

Cross said that when restaurants see higher costs, they have to raise prices or risk eroding already thin profit margins. He said the average restaurant works with a 5% profit margin and even the strongest restaurants rarely exceed 15%.

From 2020 onward Cross watched his food costs climb from the low 30% target past 40%. Beef prices have risen nearly 15% in just the past year, with ground beef topping $6 per pound for the first time in history. And unlike grocers, restaurants can’t just update their prices with a click.

“You’ve got to be sensitive about raising prices,” Cross said. “We did it in smaller increments. Maybe raise the menu prices around a dollar, then next year another dollar. But we probably should have been raising them two and three dollars, because the costs kept going up. You kept hoping the costs would come down. They didn’t.”

Customers notice. YouGov found that 82% of Americans think that restaurants have raised their prices this year and only 28% think those prices are fair.

Brewer said that tariffs have impacted speciality product prices and availability.

“There’s been a drastic difference,” Brewer said. “There are certain wines that we flat out aren’t able to get anymore. The French and Italians aren’t exporting wine like they used to because they don’t want to absorb that cost and neither do the distributors here in America. Tariffs are the worst economic idea of all time.”

Many of the restaurants that closed in the past year cited a lease disagreement as the reason for their closure. According to Redfin, the median sale price for a home is up roughly 32% over the last five years in Kansas City. As real estate prices rise, landlords will ask restaurants for more money.

Cross said rent is the one cost restaurant owners can’t easily adjust.

“The rent is fixed. You can’t change it unless you can renegotiate with the landlord,” he said. “Labor, you can cut hours. Food, you can adjust your menu. But the rent — nine times out of ten, they’re not going to lower it.”

For many operators, getting a rent increase means it’s time to close up shop.

“The rent going up is maybe the last straw,” Burris said. “Because everything’s gone up and it’s tougher to compete.”

Uncertainty ahead

Restaurants have always been a volatile business. The failure rate is brutal even in good times. But the current moment tells us how this economy is going for working people.

“The first thing people cut is entertainment,” Cross said. “Obviously, the economy is going to tell us a lot.”

The same forces squeezing restaurants — rising food costs, elevated rents, tariffs — are squeezing households across the region. The same K-shaped recovery that fills some dining rooms with people living at the top of the K clears out food bank shelves with people living at the bottom of the K.

Steady restaurant sales seem to mask that fewer people are dining out since those who can still afford it are spending more.

Some Kansas City restaurants saw the promise of the World Cup coming to town in six months, but couldn’t white-knuckle through the rising costs to make it until then.

Taken together this doesn’t necessarily mean a recession is coming. But to the households making less than $100,000, it sure feels like they are living through one.

“In about six months we can revisit this conversation, and we’ll see,” said Brewer.

This article first appeared on Beacon: Kansas City and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()