Back in the Water: Richard Dreyfuss discusses Jaws, filmmaking ahead of Planet Comicon appearance

Since 1975, Richard Dreyfuss has been bedeviled by a shark, and we are all better for it.

As one of the three top-billed actors (the others are Robert Shaw and Roy Scheider) in Steven Spielberg’s Jaws, the Brooklyn-born Dreyfuss has racked up a total of 123 acting credits on the Internet Movie Database. Still, he’ll never escape playing marine biologist Matt Hooper, who helps Chief Brody (Scheider) and Capt. Quint (Shaw) neutralize a great white shark feeding on the swimmers of Amity Island.

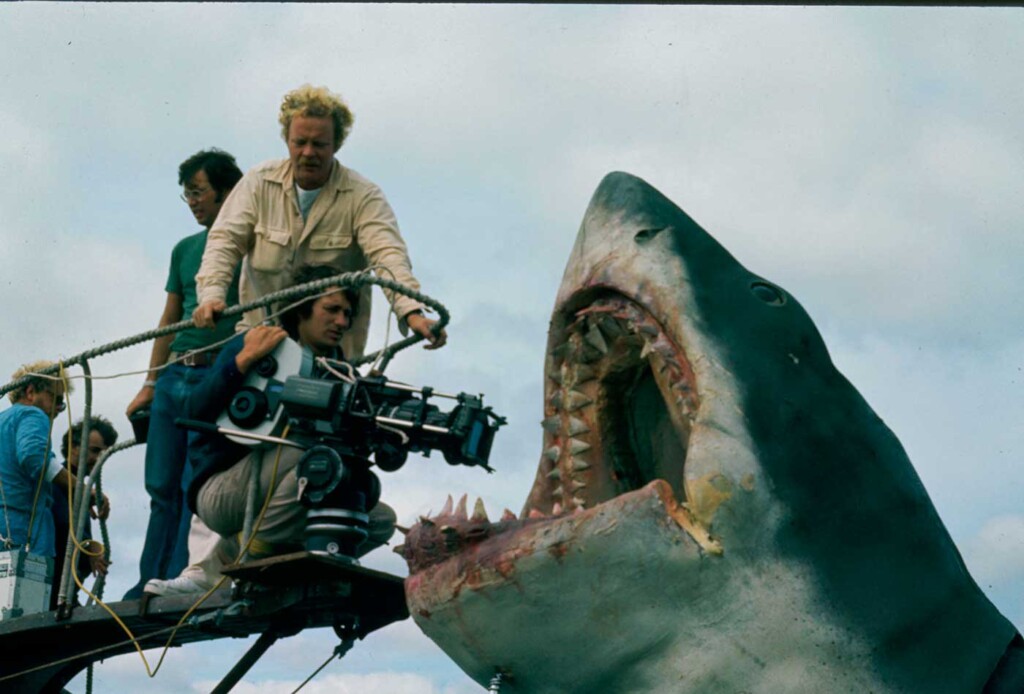

Since 2001, Jaws has been part of the National Film Registry. It’s public knowledge that the movie won Oscars for sound, editing, and John Williams’ eerie, primal score, which was Hollywood’s biggest grosser until Star Wars came around two years later. It’s also a movie that still frightens despite a difficult production and a mechanical shark that constantly broke down.

Dreyfuss is justifiably proud of the movie but has more to talk about than running the risk being fish food. On a telephone interview in 2019, he explained, “Jaws was and is one of the most powerful things that ever happened to me, one of the biggest experiences of my life, etc, etc. I usually charge people money to ask questions about it. I’ve been asked every question under the sun. This is film in general, my films, the history of film. It’s about Jaws and Steven. I’m not limiting it to Jaws. “

During our talk, we discussed the role of technology in filmmaking, the weaknesses of the auteur theory, which says that directors should be treated like the authors of books, and a lesser-known but terrific 1991 project Dreyfuss starred in and produced called Prisoner of Honor.

Dreyfuss will appear at Planet Comicon at the Kansas City Convention Center March 17-19. We caught up with him to discuss the production’s history. Despite cell reception malfunctioning as often as the shark, Dreyfuss’ insights came through strongly.

The Pitch: Jaws is probably the only scary movie one of my friends can watch. Why do you think that is?

Richard Dreyfuss: Probably because our culture is filled to the brim and overflowing with the shark and Jaws references now. It somehow softens the blow.

And I would think that there are very few people who would see Jaws for the very first time and a young age without having someone tell them, “It’s the scariest movie ever made,” so the blow is softened.

Today, Steven Spielberg is known as sort of the king of special effects, but a recent chart reveals that the number of special effects shots in his movies is remarkably low. For example, there are only about 19 minutes of dinosaur shots in Jurassic Park, and most of Jaws is about the people on Amity Island and the guys on the boat instead the beast itself.

Yeah, absolutely. I don’t think of Steven as special effects. I think that he’s the only one of our generation that had no inhibitions of genre. He’s dealt in every genre. And that makes him quite different than anybody else. He hasn’t repeated himself except when he’s gone out distinctly for that purpose.

And Jurassic Park is a world away from Jaws.

Jurassic Park, to me, is the closure, the closing of a circle. As I watched it, I saw no reason at all, ever, to forget the filmmakers from then on because they had attained an ability of such expertise that you could literally not ever see the puppets and the strings. When you went to see The Ten Commandments, you forgave it because you saw the special effects bullshit. When Jurassic Park was released, I looked at that film about as closely as one could without getting arrested. It was a perfect time machine.

It was then that I realized the only thing the industry or the art form was waiting for was the guy who could take all of film’s progress and turn it into great films. I think Steven would agree to that.

[Spielberg] would say a guy is going to be born in the next couple of years who’s going to do it all. And Steven’s personal work with George Lucas and all those others, they kind of handed the keys and the creative tools to this unknown figure who is going to be the master.

In I Blame Dennis Hopper, fellow actor Illeana Douglas cites your performance in Jaws as perfect and points to the scene where Matt Cooper confronts the mayor (Murray Hamilton) of Amity Island about the shark. Cooper keeps interrupting the mayor’s sentences and has this look like he’s going to steamroll over him. My brother is a biology professor and pauses to ensure people understand him. Cooper doesn’t. Why?

Memory being what it is—I may be getting a bit of this wrong—I think I wrote that scene in front of the billboard.

We ate dinner together every night, following Verna Fields, the editor, and her lead. She would tell Steven we need to get this interstitial shot, and you don’t need the gory this-or-that. It was at dinner that the actual script had us going from the tiger shark being strung up on the pier to the three of us meeting and going out to sea.

I said, “You have to prove it.”

You can’t say, “The tiger shark is not the [great white] shark. You have to prove it.” So that whole sequence of cutting open the tiger shark and the talking in front of the billboard came out of that.

I’ve always referred to Jaws as a sort of improvised epic. With Steven in a very, very unmistakably secure, strong lead, we started that film without a script, without a shark, and literally without a cast because I wasn’t cast until the principal photography was started. So, we were all in on it and participated, from the producer Dick Zanuck on down.

The tearing open of the shark and the billboard scene, those are scenes we had to create because there was no logic without them. I had been told by Steven when I first met him, “Don’t read the book.”

I’ve never, to this day, read the book.

I was unencumbered by the subplots [from the novel]. I know about them, but I didn’t read them. Steven said he wanted to make the film what he described as a “bullet,” an unadorned, one-click, one-chamber bang! And that’s what he did.

He made a story about a shark, period. Within the story of the shark, he had 100 mini-plots and mini-stories, but they were all in service to the one. It was an extraordinarily creative experience because there was never a question of someone saying, “No. No. No. You’re an actor. You don’t have the right to do this.”

And all of us got in on it. Good ideas came from everywhere. Because Steven had to throw out his preconception of what he was going to shoot because the [mechanical] shark wasn’t working.

We were the first film to attempt to shooting on the ocean. Every other film you’ve ever seen was shot on tanks until Jaws. So the shark, which was constructed by guys back at Universal, never had a footing on the actual ocean floor. When it rose through the salt water, it would break, so he was forced to abandon the showing of the shark as he had planned it, and he had to imply it. It was not a given.

No one assumed it was going to be successful. The studio fired Steven every night [laughs], but he certainly prevailed.

And what he allowed was logic. He never thought the inevitable, illogical reason for shooting a scene. Nor did he indulge. The first shot was the scene with all of the extras with the tiger shark being strung up. Matt goes up to the shark’s mouth and measures the shark’s mouth.

When the shot was over, a guy who was an oceanographer from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute said, “No marine biologist would ever do that.”

I said, “What do you mean?”

He said the bite power of that animal was so strong that even dead and hanging from a steel bar, it had a bite power of something like 340 tons per square inch. It could rip itself off that steel and bite your head off. So no one would come to shark that had only been dead for a few hours and measure it like that.

So, I immediately turned to Steven and said, “Let’s do it again.” And we couldn’t because the extras had already been dismissed.

But we were very proud that there are scientific errors or exaggerations in that film except for the one mentioned. Everything the shark did and was accused of doing was backed up.

It sounds like that, for all your difficulties in making Jaws, you were somewhat spoiled because of the creative freedom.

Oh, yeah. Absolutely. The first five, six, seven films all contributed to my being spoiled because in one way or another, the scripts were brilliant, the cast was brilliant, the conceptual ideal behind a film was incredible; I thought that, yeah, this is what making movies is going to be about [laughs].

I was in for some rude shocks.

Conversely, some of your challenging movies have been ones the fans seem to like. Jaws was a logistical nightmare, and Prisoner of Honor was tough, but the result was good.

Films are difficult to make. Period. The story of filmmaking is twisted and biased. Because Francois Truffaut was the man who invented the auteur theory, I got a chance to say to him, “I don’t believe in auteur theory.”

It takes more people than a director to make a movie. It’s an endeavor that probably requires the director answering more questions than any other job in the world other than the President of the United States. He’s under siege by every department at all times. What his job is, to a certain extent, is to balance out the input he’s getting and interpreting it into a coherent whole.

The auteur theory is a semantic thing that doesn’t mean anything or go anywhere, but Steven makes Steven’s films. He also makes the films that star Tom Hanks and Richard Dreyfuss and art directed by so-and-so and edited by so-and-so. All of those people have creativity flowing through them. They’re not hired because they’re not creative. They’re not hired because they follow orders only.

They’re hired because they have input, wisdom and knowledge. That’s leavened by the director. Anyone who thinks otherwise is being naïve.

Not many people talk about one of my favorite moments in Jaws. Right before Robert Shaw as Capt. Quint delivers his chilling monologue about surviving the sinking of the U.S.S. Indianapolis in World War II; your face changes from amused to astonished when Matt Cooper learns he survived it. That’s one of the most remarkable reaction shots in cinema.

There’s an answer to this: Talent will out.

If you hire good actors, you’ll hire people who know how to explore moments and phenomena of emotion. When you’re isolated, it’s like a desert island, which includes all of the research and the reading that goes on. The fact about the Indianapolis was that it was top secret when Peter [Benchley] wrote the book, so he didn’t include it. He didn’t know about it.

By the time the film had come out, it had been declassified, so Steven had made it the linchpin of Robert’s character. He had everyone you can imagine writing versions of that speech, from Francis Coppola to John Milius to Robert Shaw and everybody.

I can tell you the result, the final speech, it’s like 70% Steven, 10% Milius, and 2% something else—but it was Steven’s. And then we had that story surrounding us at all times. We couldn’t escape it. We heard it like the first people in the United States had ever heard it.

It’s such a truly powerful, awful story. Even if you tried to downplay, it comes down to X number of humans being eaten at a rate of x number per hour for seven days, whatever it is—the horror of that.

Robert had this wonderful line where he said he was most afraid after the PBY (a flying boat) had come down, and they were waiting to get on. I understood that.

In one of the extras on the Blu-Ray, you said the amazed look on your face was not acting.

It’s a compliment, but it’s meaningless. Of course, it’s acting. It’s acting on a very base level. What was that, the 130th time we heard the story? [laughs]

It had to be acting, but you let yourself go into it. One thing that’s common to human endeavor is being in the zone or out of the zone. Whether you’re an athlete, an actor, a painter, or a carpenter, you know if you’re in the zone. You are surfing. Once you get hooked into that kind of zeitgeist, if you are in tune with acting, you can be aware of it.

By the way, no one acts alone, except when the camera’s on one person for an hour and a half. I remember when I was watching Cast Away with my wife. After a certain moment, I leaned over to her and said, “You do know there are 130 people behind a camera?”

And she went, “Don’t do that!”

That’s a good thing to settle for. I brought up Prisoner of Honor because I read about the Dreyfuss affair in college. In the film, there’s one tiny scene where you, as investigator Lt. Col. Georges Picquart, see that Dreyfuss has been sent to Devil’s Island for less than a file folder’s worth of evidence. That tiny stack of papers you hold makes the injustice seem more vivid than any monologue.

Yes. As a matter of fact, I’m the only other person named “Dreyfuss” who ever went back to Devil’s Island. That’s its own story. To be attached to what was known as the most important legal controversy in the western world for so long gives me ownership rights, which is why I chose to play the character I played instead of Dreyfuss.

The story itself is true. And I underline that because what people find difficult is to realize that humanity is capable of such goofy, awful, dark, bloody shit, and at the same time, nobility. We’re all made of that.

Picquart was a very proud anti-Semite who was also the hero of the Dreyfuss affair. Dreyfuss, who was accused then, and said that if he had not been Dreyfuss, he would have been an anti-Drefusard [laughs]. He’s such a duck.

Picquart is a more active character in the saga. He’s got more to do.

Yeah. He was in civilization (France). But when you know what happened on that island and right next to that island by a matter of yards is another, bigger island, which housed of hundreds of men in the subsequent years after him. Until the closing of Devil’s Island as a penal colony, if you walked on those islands, you could hear the shrieks of pain and insanity. You could see on the walls, this scratched illustrations and cartoons and paintings done by these prisoners up until around 1946.

There’s not a doubt in Hell. I don’t know if you’ve ever traveled to Jerusalem, but when you walk in for the first time, I guarantee you you’ll go up because there’s so much God that seeps through the walls.

On Devil’s Island, the madness and terror and the loneliness and anguish of all those men are still there.

Richard Dreyfuss will appear at Planet Comicon Kansas City March 17-19.