A course on sexual assault is helping catch predators across the country, but Kansas doesn’t require schools to teach it

Kansas is one of 12 states that haven’t passed Erin’s Law. Advocates want that to change.

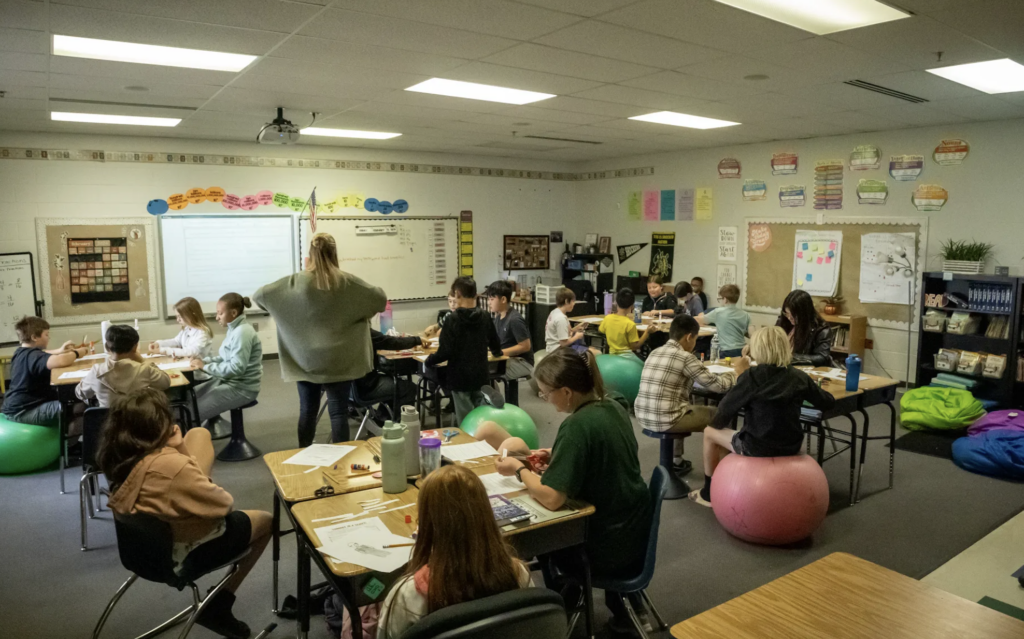

Erin’s Law would require yearly lessons on body safety for kids of all ages. (Niko Schmidt/The Beacon

Kirk Ashton was convicted of sexually assaulting 21 boys at Northwood Elementary School in Hilton, New York.

Ashton assaulted the children when he was the school’s principal from 2004 to 2021. He was convicted in 2022 thanks in part to Erin’s Law, a school curriculum that teaches children from elementary to high school about body safety.

That means teaching youth about places adults should never touch and whom to tell if something like this happens, among other lessons.

“The only education kids get around abuse is from the perpetrator, and that’s to keep it a secret,” said Erin Merryn, whom the law is named after.

Merryn was sexually assaulted as a child. Now she is focused on stopping sexual predators by lobbying states to pass Erin’s Law.

Merryn has been touring the country for more than a decade and said there are plenty of stories like Ashton’s. A predator is abusing kids, nobody reports it — but then her curriculum is taught in schools and children find out what to do.

Merryn now is focused on Kansas, one of 12 states that have not passed a body safety law. Among neighboring states, Missouri, Colorado and Oklahoma have all passed Erin’s Law. Iowa and Nebraska have not.

Her message to lawmakers is simple.

“There are other Kirk Ashtons in your state that you are preventing from being locked up,” she said.

Sexual predators don’t stop at one victim. An estimated 5% to 10% of abusers will harm more than 40 children, according to a fact sheet from East Carolina University. About 90% of children know their abusers and 40% of survivors are related to their abuser, the fact sheet said.

That’s why Erin’s Law is so important, advocates say. Generally speaking, perpetrators aren’t strangers offering candy to get children into their van — they are trusted members of the community.

Merryn said she spoke with a mother who said her daughter was abused by her grandfather. The daughter was told that if she reported the abuse, her mother would be killed.

Merryn remembers all the times she told someone else about the abuse but made them pinky promise not to tell anyone, so nobody did.

That’s how Erin’s Law is different from other training school staff goes through. Merryn said it counteracts messaging from perpetrators — telling children that some secrets shouldn’t be kept or teaching them how to report abuse.

Kim Bergman, co-director of Protecting Kansas Children from Sexual Predators, is pushing lawmakers to pass the bill. She was sexually assaulted by a gymnastics coach at 12 years old. She didn’t report the crime and the coach went on to assault others.

Bergman, who grew up in Lawrence, doesn’t remember any similar lessons from her childhood.

“This is not a Republican bill. This is not a Democrat bill,” Bergman said. “This is a bill simply for everybody — for kids and protection and prevention.”

She has been talking to state lawmakers who are open to passing the bill. As written, it would require yearly training. That could be school counselors, teachers or sexual assault centers. Teachers would also have training on sexual abuse that could help them spot warning signs. Parents could opt their children out of the lesson if they wanted to.

There is a free curriculum online for teachers to offer Erin’s Law classes. The courses are ideally taught in each individual classroom, said Brandy Williams, director of education at the Metropolitan Organization Countering Sexual Assault.

Williams said MOCSA is offering courses in Kansas schools now. She said they are tailored to students’ ages, like cartoons for younger children and conversations about consent for older students.

It’s a year-round process in both Kansas and Missouri that keeps her staff busy. But there are still schools that aren’t getting this training. Williams hopes the legislation will sail through the Kansas Statehouse, because she doesn’t see any reason it wouldn’t.

Her message to skeptical lawmakers is straightforward.

“I would want to know what their concerns are and what they feel would happen if this law did pass,” Williams said. “It doesn’t feel to me like there’s any harm that could come from this law passing.”

This article first appeared on Beacon: Kansas and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()