Smoke Show: Missouri wants to protect children via cannabis ban, but small businesses will need a band-aid

Back in August, Missouri Governor Mike Parson announced Executive Order 24-10, prohibiting the sale of any food containing unregulated psychoactive cannabis compounds, as well as prohibiting liquor license-holding retail businesses from selling psychoactive cannabis compounds. The order was originally planned to take effect on Sept. 1, where the DHSS would be in charge of embargoing and condemning any of the respected products that fall under the order.

Although Secretary Jay Ashcroft refused to sign the order, Parson claims that it has not halted the DHSS from investigating nearly 60 facilities containing the products in the state.

“When Secretary of State Ashcroft denied the emergency nature of the executive order, we felt a little bit of relief, but there was still an issue with DHSS going out and visiting stores and distributors, and targeting what mostly was legal products, because they didn’t seem to really understand their own parameters,” Missouri Hemp Trade Association Secretary Craig Katz says.

Among these raids, one in particular highlights the unhinged, scattershot approach to enforcement the state has adopted in this limbo between announcement and official enforcement.

On Sept. 11, the DHSS decided that it would be appropriate to investigate the Franklin County VFW (Veterans of Foreign Wars) Post in response to a complaint that the bar was selling a hemp-derived THC seltzer—UR Lit, containing 5mg of delta-9 THC. For a space intended for veterans to gather safely, it is completely unfathomable that the DHSS would even consider conducting the investigation on a day when many citizens, veterans or not, are mourning the loss of thousands of lives—or personal ties—to 9/11.

“It kind of was the straw that broke the camel’s back, I think, in terms of what the administration was doing, because it was certainly an inopportune time for them to have done that,” Katz says about the investigation on Sept. 11.

In a press release that Gov. Parson issued shortly after announcing the executive order, he states that his decision to stop the sale of these unregulated products came from “a recent increase in availability of products containing psychoactive cannabis and the emerging concerns regarding the health effects of these substances, especially among Missouri’s youth.”

Missouri Attorney General Andrew Bailey announced that the Missouri Division of Alcohol and Tobacco Control will submit actionable referrals to Bailey’s office through a “dedicated electronic repository” to take account of investigated retailers and decide on further action.

On Aug. 30, the Missouri Hemp Trade Association filed a lawsuit in the Cole County Circuit Court against the State of Missouri, stating that the products are not considered “adulterated” under the state law. Shortly after, the DHSS issued a memo to retailers on how the order would go into effect.

Last Tuesday, Sept. 17, general counsel for the DHSS Richard Moore issued a letter stating that the department will only aim at embargoing and condemning the products that would fall under trademark infringement.

“In regard to psychoactive cannabis products, the department will focus its efforts on the identification of ‘misbranded’ products,’” Moore said in the letter.

“Judge Walker, I believe it is, basically made the Attorney General’s office put on the record what was contained in the letter that they had sent, that they were going to stop trying to enforce against legal hemp products, and that they were only going to be trying to enforce against the look alike products and the trademark infringement products. And, I think he made it clear to them that if they did not comply with what they were putting on the record, that we would be back in court,” Katz says.

While the declaration is intended to help uplift and protect Missourians—specifically children—from potential threats from the substances, it could be doing more harm than good.

Many professionals within the hemp industry around the city and state as a whole are having to regroup and consider plans to combat, and/or abide by, the potential changes before they are left with a revenue loss from the product ban, or worse, disciplinary actions for noncompliance.

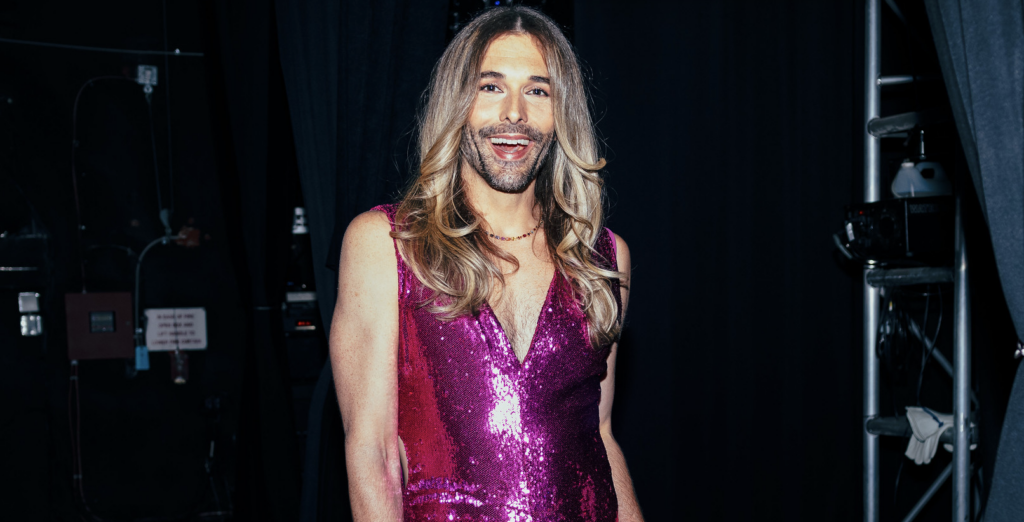

KC Smoke & Vape—a local retail business that has been in KC for nearly 30 years—will have their revenue directly affected by the executive order, although they claim that their products are privately tested and are not being sold to minors.

“Anything that we carry, for instance, the first thing we do when we get it in is we check it for a COA, certificate of analysis. We check and see exactly what’s in that product. We make sure that COA actually matches the information that’s on the packaging, and then we go from there,” KC Smoke & Vape owner Jason Ballou says. “There’s not a thing that we sell that does not have an actual COA from a federally licensed testing lab that accurately reflects what is in that product.”

Ballou claims that on top of the testing analysis that the products that his business distributes undergo, they also use child-proof packaging and veer away from manipulative manufacturing practices.

“All of the packaging that we use are child-safe containers, or they’re specifically designed to make them child-resistant. We also don’t make gummy bears or gummy worms or anything like that,” he says.

At the conference that Parson held in August, he provided examples of manipulative marketing within the hemp industry—delta products that were packaged to look nearly exactly like popular candy brands, such as LIFE SAVERS, Mike and Ike, and Airheads. Ballou says that KC Smoke & Vape has never sold items of these kinds.

“We’ve been selling these products since 2019, and we’ve never sold a single package like that. I think, from a marketing standpoint, that’s absurd and ridiculous and should not be allowed. But also copyright infringement, moral—everything is wrong about that,” Ballou says.

“We understood the idea behind wanting to get rid of the look alike products, the counterfeit type products that were appearing in packaging that looked like it was children’s candy,” Katz says. “Look, our industry wants that stuff out. The legitimate people in our industry do not want those products on the shelves because, A, they’re dangerous, B, we have guilt by association.”

The Missouri hemp and cannabis industries are very closely related, yet differ incredibly in terms of regulation, which is why Parson’s order came into debate in the first place. Professionals in both the hemp and cannabis industries believe that there must be a better way to regulate the products without banning them completely.

“I really think that the rules and regulations that the DCR (Division of Cannabis Regulation) has posed for packaging, labeling, and all that good stuff didn’t come in a vacuum,” Illicit Chief Marketing Officer David Craig says. “It was from years of research on other legal recreational and medical markets. Those are best practices followed in some fashion across the country, in the 20-some-odd states that have legal cannabis. And so, to basically ignore that because the specific cannabinoid doesn’t fall under their purview, I think it’s really short-sighted.”

“We actively support there being regulation, not just on hemp edibles, but any kind of a consumable hemp product, or even topical hemp products,” Ballou says. “But really, those regulations should center around packaging, testing, things like that, so people actually know what they’re getting.”

Among members of either industry, there seems to be a consensus surrounding where the E.O. stems from. Obviously, manipulative business practices are taking place in the state, ultimately putting consumers, specifically children, at risk, but some believe that hemp retailers are conducting moral business while bad actors are bringing the industry down.

“Obviously, reputable stores will enforce the minimum age, but you can go to just random, generic gas stations and buy them at any age, which is ridiculous,” Ballou says.

“There are certainly companies, manufacturers, and all those things who are doing their best to follow the rules to the best of their ability,” Craig says.

“The hemp industry is willing, able, and eager to cooperate with the legislature and the state in terms of formulating reasonable rules and regulations to regulate the hemp industry,” Katz says. “We have no problem with that—age limits, labeling, any of those things, childproof packaging, there’s no issue from the industry with that. The industry is made up of good actors, and many of these are small mom and pop operations, where it’s literally their only source of income. If the governor’s E.O. had gone into effect, you would have a lot of people who were out of business and a lot of people out of jobs.”

If Parson’s order were to follow through pending the delay, changes would obviously be seen within the hemp market, but maybe to an extent further than the average consumer may realize.

“Raw hemp seeds that you may be adding to a salad, or you may be adding to your food, protein, any hemp oil that’s extracted from those hemp seeds—anything that a bagel has got hemp seeds on it, any of those products potentially have THC in them. But, under the wording of this law, it doesn’t matter if that THC is enough to actually get you high. What matters is whether or not it has psychoactive, unregulated THC and all of those hemp seeds potentially have unregulated, psychoactive THC in them,” Ballou says.

“Hemp is used for other other purposes, other than health related issues,” Katz says. “It makes clothing, it makes furniture, it makes rope, it makes, there’s all sorts of things that it’s used for. And once you get into where the governor’s order was going, it gets to gray areas. It’s, again, a difficult situation for the industry and the people who depend upon it for their livelihoods.”

While many may consider them competing industries, professionals in the line of work see them as sister industries that are on the rise together. After all, both are incredibly scrutinized professions that have gradually etched their way into a part of individual’s daily lives.

“We’re huge advocates for hemp because we all kind of went through the same thing, trying to work through these federal restrictions, local state restrictions together,” Craig says. “So, we want to see them grow as much as everybody wants to see us grow. It’s just consumer safety, clarifications, regulation.”

Speculation of the DHSS stepping in to regulate hemp in similar ways that they monitor the cannabis industry is a suggestion that professionals in both sectors have.

“You can do nothing, leave it as is, which we’ve discussed why that’s a danger to the public. You can completely ban it outright, which might hurt some small businesses, which nobody wants to do. And then, maybe there’s a middle ground where it just falls under some sort of regulatory oversight, either with the Department of Cannabis Regulation or some sort of offshoot,” Craig says.

It will be interesting to see where the E.O. takes hemp production in the coming months, but it is important to note that the hemp industry and members of the cannabis market agree that the ban takes too far of a stance on hemp-derived products, and will come at a large cost to local small businesses.

“The idea of just coming in and completely banning a category for reasons that appear based on the actual numbers and statistics to be completely unjustified just seems like complete overreach,” Ballou says.

“I think, you could probably say that you’re you’re going to be looking, at least in the next several months, at a safer environment for the consumer, because the ‘bad products’ will be taken off the shelf, and the legitimate and ‘good products’ will be allowed to be sold,” Katz says.

It will not be until the governor’s next session, regardless of if Parson is office or not, until there will be major updates on what the future holds for the delta products, but the ‘bad products’ that Katz discusses seem to be clearing shelves as the attorney general’s task force controls the embargo process.