50 Years of Hip-Hop in KC: A history of our first half-century from house parties to Hammer Time to Tech N9ne

No Coast rap culture runs deep.

This summer marks the 50-year anniversary of hip-hop. The culture was “born” August 11, 1973, in the South Bronx, when Clive “DJ Kool Herc” Campbell, the man known for creating the breakbeat, threw a back-to-school party for his sister. As the world takes time this summer to reflect on the complicated, beautiful, weird, wild story of this uniquely American art form and its impacts, we have to reckon with large gaps in that story where marginalized history was under-documented or erased entirely.

Among those important details overlooked is an entire arc of our metro’s specific strain of the form. While there are endless books and podcasts about this city’s proud tradition of KC BBQ or KC Jazz, we’ve been a power player in the rap scene since its very inception.

Taken from dozens of interviews with the people who were there, this is a look at how this much-maligned phenomenon impacted Kansas City and the rappers, DJs, dancers, graffiti artists, producers, and promoters who made it happen—much of the time against impossible odds.

“Laugh and Dance” by Omer Coleman II a.k.a. Starship Commander Wooooo Wooooo (1981) — The first rap record in Kansas City.

Masked Up

Arthur Davis, a former session drummer for Stax Records, worked as a substitute teacher for the Kansas City Missouri School District starting in 1980. He used his connections to convince the school to allow him to throw the legendary events where young Blacks gathered to dance, listen to music, and socialize on weekends overnight until early morning.

Hiding his identity as a teacher—and a grown man double the age of the kids he was entertaining—Davis organized and performed from behind a latex Richard Nixon mask. “Mr. President” knew how to throw a party, and these evenings served as the launching pad for a burgeoning music scene.

Affectionately called “The Castle on the Hill,” Lincoln High School was the epicenter for early hip-hop culture in Kansas City—long before it became a pinnacle of academic success. Admission generally ranged from one to three dollars. Davis himself was not a DJ. He hired a crew of turntablists (Vincent D. Irving, aka DjV, and Delano “Silky Smooth” Walker) who played the music. For most who attended these all-ages parties, this was an introduction—and the only real access available—to rap music in any form. Even the local radio stations, including Black-owned KPRS (Hot 103 Jamz), mostly avoided the genre at the time.

Davis and his crew of DJs marketed the parties guerrilla-style, distributing crudely produced fliers around the east side of Kansas City. After a couple of years of success, Davis began promoting the parties on KPRS by purchasing the least expensive airtime possible—late at night and on the weekends.

The parties were attended by thousands and were nonviolent affairs where high schoolers mingled with young adults as they danced, networked, and had fun listening to classic rap songs like “The Breaks” by Kurtis Blow, “That’s the Joint” by the Funky 4 Plus 1, and “Body Rock” by The Treacherous Three.

Soon these parties spread to other high schools, and DJ crews like Robert Harris and the Knights of the Sound Tables, Sergeant Oooh-Wee, Shawn Copeland, The Inner City Player Macks, and D. Mustafah began promoting parties at Paseo High School, Southeast High School, and Southwest High School.

Vonzell Bryant, a veteran DJ and entrepreneur, took things to the next level and became the premiere party promoter of the city during the ‘80s. Under the moniker Captain Vonzell, he threw his first party at the Boys Club on 43rd Street and Cleveland in 1973.

“I played mostly slow jams and disco,” says Bryant. “The element that made it hip-hop was me on the mic talking trash and giving shout-outs to keep the crowds hyped.”

Bryant’s entire approach to spinning music at parties changed after a trip to New York City in 1978. While in the Big Apple, he was introduced to the culture of rapping, beatboxing, DJing, breakdancing, and graffiti. He witnessed what is called the five elements of hip-hop and brought back what he heard and saw—an importer of the sights and sounds of Blackness future. Like all things new, early adopters experienced a few… hiccups.

“I started scratching and mixing records at my parties,” says Bryant. “But the people wasn’t with all that. They would yell at me, ‘Hey, quit fucking up the music.’ It eventually caught on, but it took a while.”

Rage & Reaganomics

Like most urban sprawls in America, the socio-economic situation for most Blacks in Kansas City was harsh and extreme during the late ‘70s and ‘80s. The area was in severe social and fiscal decline, which added fuel to the fire for a metro that historically has looked to abandoning its marginalized populations at the drop of a hat.

The famous corner at 12th and Vine Street, referenced in the most popular song ever recorded about Kansas City, was bulldozed to build housing projects—18th and Vine was left for dead. The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum was housed in a tiny closet. Gates and Sons Barbecue and Arthur Bryant’s Barbecue struggled for years for relevancy and respect. All of these setbacks were actually ingredients for the perfect recipe for a new sound and style of music—among a community that knew it needed to get loud to avoid being dissolved from its place in society.

While rap music was heavily restricted in both radio airtime and live performance venue options, one platform that couldn’t be stopped was the distribution of movies. Hollywood’s influence was heavy as thousands of young Black youth absorbed everything they saw like super sponges. A string of movies, Wild Style in 1983, Beat Street and Breakin’ 2: Electric Boogaloo in 1984, and Krush Groove in 1985, would showcase the sights and sounds in a manner that the region’s typical censors couldn’t filter away.

One of the first to turn cinematic inspiration into reality was Marcyl Goode.

“I was blessed that I saw the hip-hop documentary Wild Style at an early age,” says Goode. “Movies definitely intrigued and inspired us and were our visual connection to the culture. The influence was real.”

“Kut of the But” by Kutt-Fast (1989) — First Kansas City rap artist to have a song distributed.

As a young child, Goode hung out at a convenience store owned by Captain Vonzell on 35th and Prospect. There was an arcade in the back where kids gathered to play Pac-Man, Donkey Kong, and Centipede. The real attraction was that it was a ‘safe haven’ where kids went to socialize, dance, and listen to the rap music that Vonzell played.

Under the tutelage of Vonzell, who functioned as a father figure, Goode became somewhat of a DJ prodigy at age 10. He soon joined Vonzell’s P-Funk All-Star crew under the name “The Young Marcyl Goode” and began DJing at school social events and parties.

“It was something I just did for fun,” says Goode. “I was just the kid with the big boom box hanging by the big fountain at the Country Club Plaza playing rap music.”

Goode lifted his stage name, Kut-Fast, from a lyric off of a Mantronix song called “Fresh is the Word.” He released his first single in 1989, a song called “Butt of the Kut” on Intrepid Records. It is often credited as the first rap song professionally produced in Kansas City.

However, that distinction technically belongs to Omer Coleman II, aka Starship Commander Wooooo Wooooo. On his 1981 album Mastership, he released the rap classic “Laugh and Dance.”

“‘Laugh and Dance’ is an important song because Woooo Woooo exposed a new sound to an R&B heavy market,” says DJ Will Burnell. “It was a good song for the times, and it matters because it would play a part in influencing the Black Futuristic movement.”

Goode’s “Kut of the Butt” sounded more like a traditional rap song than “Laugh and Dance,” which came off more funkish than hip-hop. Another example from the dawn of the scene can be found in Bloodstone’s 1982 song “Funkin’ Around,” which features a rap interlude. The doo-wop crew from Kansas City was primarily known for silky smooth ballads but leaned into something harder on this recording.

“Kut of the Butt” was produced by high school friend Tony ‘Prof T.’ Tolbert and Lance Alexander, both of whom were members of the R&B group Lo-Key? which hit number one on the Billboard Hot R&B Singles charts in 1993 with “I Got a Thang 4 Ya!” The duo had a production deal with Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis at Flyte Tyme Records in Minneapolis but stayed connected with artists out of the metro.

The song was only modestly successful, lacking the proper distribution and adequate radio airplay to become a hit—a common theme for most rap artists in KC at the time.

“I’m rap broke because I was too early in the game,” says Goode. “But I’m satisfied because I know I helped pave the way for everyone else to succeed.”

Goode would continue his pursuit of glory by teaming with a neighborhood ally named Antonio “T. Roma” Cody, who started Bizniz Records. Roma capitalized by pushing products through liquor stores, gas stations, and mom & pop grocery stores. It was a blueprint that would soon be used by several local rappers that would result in tremendous success, in particular for a young street hustler turned rapper—Richard “Rich the Factor” Johnson.

Rich the Factor is considered Kansas City’s most successful “self-contained rapper.” Over the course of three decades, beginning in the early ‘90s, the artist sold hundreds of thousands of albums, mostly hustled out of the trunk of his car and through consignment at small independently owned record stores like 7th Heaven. Factor became a street legend with a cache that rivaled the biggest names the scene would ever produce.

Aaron Dontez Yates, later known as Tech N9ne, as an infant in Kansas City, Missouri. // Courtesy Strange Music

Anonymity Sucks

During the ‘90s, rappers sprung up like dandelions on an untreated lawn. Rhyming over breakbeats became an obsession for many young people, and our city was no different. But chart success and national recognition mostly skimmed over the metro’s scene, and KC’s inability to produce a signature, definable style hadn’t helped the cause.

During the ‘90s and early ‘00s, most rappers from the area leaned toward the West Coast sound, primarily out of the Bay Area (San Francisco, Oakland, and San Jose). The proliferation of crack cocaine arriving at the prairie land brought with it Oakland’s sound and, hand-in-hand, an extension of its violent street gangs. Crips and Bloods became local traffickers, and suddenly everything from their lifestyle, vernacular, dress, and beliefs became a reality in our space. This had an immediate impact on many young Kansas Citians, in particular those striving to become rappers and the individuals who produced the beats.

The West Coast sound was slower and more melodic than the types of rap produced on the East Coast. The delivery was closer to that of blues singers and had field holler-like cadences. It was a mix of early gangsta rap and what would eventually become the sound synonymous with the Dirty South.

The odds for success were stacked. There was no music infrastructure in Kansas City. Record labels didn’t set up affiliate offices and were also reluctant to sign artists for this unproven part of the country. Very few recording studios were receptive to young Blacks using their facilities. When they were allowed, they were often overcharged for recording time, and only late hours into the early morning were available for use.

Legitimate venues and nightclubs that allowed the culture to thrive were in increasingly short supply during the ‘90s. The East Side high schools that used to allow parties began to shutter the idea due to the increase of violence. Promoters then began throwing parties at hotels, motels, and union halls. These new outlets generally went well until they began overcharging, and a flag-burning incident by a performer at Crown Center caused the hotel to push pause on everything.

The last venue connected to the Kansas City, Missouri School District that still allowed events was the Southeast Field House. It was a 3,000-seat arena primarily used for high school basketball and volleyball games but is more famously known for the talent shows and drill team competitions that were held there in the ‘80s and ‘90s.

During the ‘90s, Chancellor “Chance” Cochran began producing events. He was a self-taught promoter who put on a series of Anti-Violence Concerts from 1996-1999. Then he created the largest hip-hop event in KC history with the May Day Beach Bash in 2000. The localized Woodstock-esque show drew 30,000 attendees to the International Speedway in its second year. That success proved to be its demise, as it turned out venues were increasingly wary of letting tens of thousands of teens and young adults gather in one place to get “amped up” on rap.

On 40 Highway, Ryonell “Romeo Ryonell” Frederick, a rapper and DJ who found more success as an entrepreneur, began leasing the old Heart Banquet Hall and converted the facility to Frederick’s. Every weekend for five years, the building would be packed with young adults soaking up the new sounds via a de facto nightclub. A barber by trade, Frederick created Barber Shop records and used the venue to showcase his roster of talent, including rappers and DJs.

The Flavorpak Crew in 1995. (Pictured L to R) DJ Ran, David Rogers, Gear, Scribe, Jeremy McConnell, Mike Martin and Armando Diaz. // Courtesy Flavorpak

One of the biggest platforms in the city’s history for rap artists was Black Expo USA. The consumer trade show was produced by local businessman Elbert Anderson—who also owned KCXL 1140 AM radio, a station slightly more congenial towards rap than Hot 103 Jamz at the time. The station had a daily ‘call-in’ show on weekday afternoons. “The Dedication Line” was hosted by Darryl Johnson from 1984 to 1988, where the on-air personality played hip-hop instrumentals as callers dropped shout-outs.

Beginning in 1992, vendors from all over the country would converge at Bartle Hall, providing thousands of attendees the opportunity to purchase Black art, hair care products, and Afro-centric clothing—all items that were difficult to obtain in the pre-Internet era. A big component of the three-day event was entertainment performed on a massive stage inside the convention center. However, the stage was reserved for R&B, Gospel, and Jazz acts. Rap artists were barred from performing—deemed not ‘family-friendly.’ Instead, they were allowed to perform at the event’s annual step show held in the Municipal Auditorium.

Local rap acts would perform between the college fraternities and sororities who came in from around the region to perform their step routines. For most of the acts, it was the largest audience they had ever performed in front of. The arena was packed to capacity with 10,000 screaming kids and young adults that had come from steppers and were subtly indoctrinated into the future.

The Dyamund District

In the ‘90s, the general mentality of most rap artists was to get signed to a major music label, make lots of money, and buy their parents a house. It wasn’t because of a lack of trying, but obtaining national exposure was not an easy proposition—increasingly leaving even the scene’s biggest stars with a dream deferred.

No one struggled with navigating the tricky waters of the music industry more than Tech N9ne. The rapper went through a period of failed deals, bad deals, and no deals. His first signing was with Perspective/A&M Records in 1993. Creative clashes led to the contract termination in 1995. In 1997, a chance encounter with Quincy Jones’ son Quincy Delight Jones III—known as QDIII—led to his second deal in 1997. Once again, “creative misunderstandings” yielded a sudden endpoint.

“Every label I signed to pushed me to deliver more commercial-sounding music,” says Tech. “I never felt comfortable producing corny popcorn shit.”

To the rescue came Dyamund Shields and DaJuan “Don Juan” Cason—the two grew up together in the same neighborhood. Years later, Don Juan convinced Shields to help him start a music label. Shields was looking for a way to diversify the large sums of money he made slinging dope on the streets. Together they formed Midwest Side Records—a micro-Kansas City version of Death Row Records in 1995.

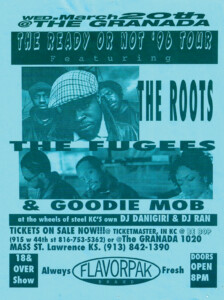

A Flavorpak concert flier promoting The Roots in concert at The Granada Theater in Lawrence, Kansas. // Courtesy Flavorpak

Midwest Side Records had the magic formula. Initially, Shields and Don Juan had a well-orchestrated plan. Shields, a highly successful drug dealer with the business prowess of a Fortune 500 CEO and the temper of Suge Knight, financed the label. Production wiz Don Juan created the beats, and Tech N9ne, a generational talent, brought a unique lyrical flow, hyper personality and energetic stage presence. Success was at their fingertips, but drama fueled by egos and bad business decisions derailed it all.

Shields, who called himself Boss Hoss, was a two-headed monster. He could be playful and fun-loving and deadly-serious and violent. His temper was a thing of legend, but he was also highly respected for his business acumen.

During Tech N9ne’s brief but impactful tenure at Midwest Side, he released his debut album, The Calm Before the Storm in 1999 and the follow-up The Worst in 2000. Don Juan produced nearly every track on both albums. For many, these two early releases represent Tech N9ne at his hungriest and best. The single “Planet Rock,” one of the first local rap songs to dominate local urban radio, was a byproduct of this mini-dynasty run.

The relationship between Tech N9ne and Shields soured over the future vision of the company. The pair parted ways in 1999. Although it was an amicable split, both sides remained unhappy, leading to beef that resulted in Shields releasing a collection of Tech N9ne songs as an album called Celsius without the rapper’s permission. The bootleg record became a street hit.

Tech N9ne admits that the two had quiet and mutual respect for one another all the way until Shields died from pancreatic cancer in 2017. Don Juan continued producing music for himself and others, including E-40, Crooked I, and a laundry list of local artists.

Zine Dream

Amid the violence that began to plague Kansas City during the early ‘90s, a movement was born. Jeremy McConnell, a transplant who grew up in St. Louis, enrolled at the Kansas City Art Institute in 1989. The 19-year-old majored in sculpting before switching to printmaking.

McConnell got into hip-hop during middle school in St. Louis by listening to Majic 108 and Dr. Jockenstein, who let listeners rap on air over beats during his roll-call show. A blend of early rap fandom mixed with punk and alternative rock melded into an ethos the kid could use. McConnell’s fascination with scene ‘zines’ led to the creation of Flavorpak.

“When I came to Kansas City, I was into independent publishing,” says McConnell. “You had these kids creating magazines by Xeroxing copies of pages and stringing them together. It’s how we expressed ourselves way before social media.”

The first issue of Flavorpak was published in 1993. It was 40 pages and featured comics, poetry, creative writing, illustration, photography, and music reviews. It was low-budget and self-published and consisted of just one color.

McConnell had planned on the zine being a one-time thing, but its popularity skyrocketed.

“People kept asking for the next one,” says McConnell. “It started out with a mix of stuff but the elements of hip-hop were always included. Flavorpak was never meant to be a version of The Source magazine. It just happened to catch on with a lot of hip-hop heads.”

In order to increase circulation McConnell began throwing parties, then used the party proceeds to publish higher quantities of the magazine. The first event was in 1993 at an empty warehouse in the Crossroads years before the area’s rebirth—students from the Art Institute, skateboarders, backpackers, people from the rave and club scene, and hardcore hip-hop heads all gathered. Five dollars. No alcohol.

“The parties included DJs, rap performances, rock, and art bands,” says McConnell. “Later, I decided to put more energy into hip-hop because they had fewer places around town to perform.”

Local venues were reluctant to book rap acts due to their ignorance of the culture. “They always assume the worst when it comes to hip-hop,” says McConnell. “We personally never had fights or any gun violence. The only time we had guns drawn on us is when the police shut down one of our parties in the West Bottoms.”

The Flavorpak brand really made an impact on the city when McConnell began doing street promotions and attaching the brand name to national hip-hop shows—that included performances by Nas, The Roots, The Fugees, and Common primarily at the Granada Theater in Lawrence. McConnell was allowed to book opening acts using local talent which led to the rise of Papa Calv and the Loli Pop Kidz, Vell Bakardy, Ill Brew and DVS Mindz out of Topeka, Kansas.

“Flavorpak was a collective of like-minded creative people,” says McConnell. “There were incredible graffiti artists like Donald “Scribe” Ross, who was from Boston, and Gear Smith, who is from Kansas City. DJs Thomas “Joc Max” McIntosh, Dani “Dani Girl” Cardinale, Candace Cooper, Theo Parrish, and Hakim “DJ Hike” Atwood made names for themselves spinning vinyl at our parties.”

Flavorpak is now 30 years old, still out there sporadically throwing parties and promoting live music. McConnell is more than aware that even with all the progress made, breaking through as a youngewr artist in this scene is still harder than almost anywhere else in the music industry—both in genre and location. Even with KC’s star consistently on the rise, the upward battle has never been afforded even the most basic of shortcuts. Some things never change.

MC Hammer and members of The Imperial Preps at the American Music Awards (1991)

Hammer Time

In the fall of 1990 MC Hammer’s tour came to town. During the show at Kemper Arena several members of the Imperial Preps dance crew got called on stage during intermission. These former members of the Marching Cobras drill team pounced on the opportunity. An impromptu dance battle between The Imperial Preps and Hammer’s current roster of dancers broke out.

The Imperial Preps, who had home court advantage and better dance moves, blew the crowd and Hammer’s dancers away. Hammer missed the entire battle probably because he was backstage changing clothes.

The next day a meeting was set-up for the members of the Imperial Preps who formally auditioned for Hammer.

In the Spring of 1991 they began touring with Hammer right as his stage show became even more elaborate. According to Tech, he purposely chose to stay behind to focus on writing music and rapping. For other members of the Imperial Preps—Nezester “No Bones” Ponder, Richard “Swoop” Whitebear and Russell “Goofy” Wright—they left and jumped on the Hammer train for the ride of their lives.

The group was tremendously instrumental in helping Hammer craft an uber energetic stage show that would help the rapper ascend to international stardom. It was an elaborate almost circus-like presentation with dance as the centerpiece. The MC Hammer tour at the time was the largest most successful rap tour in the history of the culture.

The height of The Imperial Preps’ journey into Hammerland came when Ponder and Wright danced at the American Music Awards as Hammer accepted an award on stage in front of millions watching on national television. Ponder, who was famously known for his triangle freeze hairstyle was also prominently featured in Hammer’s Taco Bell commercial.

Hammer’s excessive extravagance came at a cost. The rapper famously declared bankruptcy and his fame quickly faded mostly due to an onslaught of attacks from the hip-hop community that pushed back against what they considered a lack authenticity because of his over the top representation of hip-hop.

After their run with Hammer, the dancers who introduced his signature dance, the pop-shake made famous in the “They Put Me in the Mix” video, found plenty of work. Ponder danced for Madonna, Michael Jackson, Mariah Carey, Missy Elliott and Destiny’s Child. He also choreographed for Destiny’s Child and Monica. Whitebear went on to choreograph for Brandy and Aaliyah. And danced in movies including Stomp the Yard, Save the Last Dance, and You Got Served. Wright did choreography for the Backstreet Boys and other pop groups.

“4, 5, 6” Sole (1999) — Sole becomes the first rapper from Kansas City to gain worldwide exposure. The song hit number 21 on the Billboard Hot 100 and was the second biggest rap song of 2000 on Billboard’s Hot Rap Singles chart.

Locked and Loaded

Tech N9ne actually began his foray into hip-hop as a dancer. “From rhythm came rhyme. I was a pop-locker and break dancer. From dancing came my style,” says Tech who begrudgingly went solo after years of performing with Nnutthowze.

Tech N9ne is arguably the most successful independent rapper ever, but getting to that point was full of potholes and loaded with detour signs. It was a very disheartening journey that began early in his life.

Born two years before the birth of hip-hop, Tech grew up in the Wayne Minor housing projects as a young child at 904 Michigan Avenue. Eventually his family relocated south to 59th and Swope Parkway then eventually to 58th and Forest where he lived with his Christian mother and Muslim stepfather.

Tech N9ne struggled with early rumors of being accused of being demonic and a devil worshiper. The accusations were mainly based on his appearance. “I remember just being the weirdo with the red-hair and painted face,” says Tech. “I’ve always felt like an outcast but it all worked out.”

Tech grew up Christian. As a child he attended church nearly everyday with his grandmother.

Family friction caused Tech to leave home at age 17. Initially a dancer, Tech soon discovered his vocal prowess. Tech joined forces with three friends to form the group Nnutthowze.

The group performed regularly around town and recorded an album produced by Sean “Icy Roc” Raspberry but tangled legalities and bad business decisions prevented it from ever being released.

Tech’s style is one of the most unique in the genre. His rapid-fire style of delivery influenced his name which was given to him from fellow rapper Walter “Black Walt” Jefferson in 1988. Tech, who wrote his first rhyme in 1985 wouldn’t find success as a rapper until 2006 with the release of the album “Everready.”

The creation of Strange Music was Tech’s salvation. The music label was built from the ground up. It started out as Tech’s mantra, plucked from his time spent listening to The Doors as a youth, to eventually becoming one of the most successful independent labels in the history of the genre.

Tech N9ne met Travis O’Guinn in the summer of 1998. O’Guinn, who inherited his family furniture business, Furniture Works, was a teenage millionaire looking to jump into the business of hip-hop. Tech had the mind boggling ideas, work ethic and creative vision and O’Guinn had the money, business savvy and strategic vision.

Together the pair came up with a plan of steady album releases, constant touring and pushing tons of merch. Nearly 25 years later the well-executed plan landed Tech N9ne on six continents, Billboard charts and the Forbes list.

“O.G.” Tech N9ne (2010) — The best example of the merger of Hip-Hop and Kansas City black culture. The song appeared on the album “The Gates Mix Plate,” a celebrated homage to Tech N9ne’s favorite barbecue spot and its legendary owner Ollie Gates.

Strange Music was officially created in 1999, perhaps the greatest year ever for Kansas City hip-hop. The creation of Strange Music was the beginning of a new direction for Tech N9ne who would soon become the biggest name on the Kansas City hip-hop scene. That same year Tonya Johnston, now Aja Shah became the first rap artist from Kansas City to receive massive exposure. Born the same year as hip-hop, Shah began writing rhymes and poetry at age 13.

During middle school in 1986 she and a friend, Shurhea Mitchell, formed a group called Divine. The duo called themselves Desire (Shah) and Obsession (Mitchell). Inspired by Salt & Pepa the pair performed at talent shows and recorded a demo produced by Raspberry. There was huge promise but the duo failed to ever sign with a music label. The two later attended separate colleges and the group faded.

Years later Shah met producer Christopher “Tricky” Stewart through newly established music industry connections. At the time he was in the planning phase of producing his first rap record with Miami rapper JT Money. Her feature on his hit song “Who Dat” which climbed as high as number five on the Billboard Hot 100 chart became a massive hit. Soon after Shah, who called herself Sole at the time, landed a production and record deal.

Off the momentum of that hot song and even hotter appearance in the video clip for the song Shah released her solo album “Skin Deep” on DreamWorks. The perfect combination of sex appeal and agile lyricism helped propel her to become one of hip-hop’s early successful female artists. Not to mention the biggest rap artist at the time out of Kansas City.

“Life shifted so much after I got my deal,” says Shah. “I wasn’t the person people perceived me to be. When I performed I was a character. In real life I wasn’t a party girl. I was a nerd, a cool nerd, but a nerd. I graduated from Lincoln College Prep High School. The things I rapped about wasn’t my life.”

Disillusioned with the music industry, Shah voluntarily called it quits soon after the release of her debut album over the hyper-sexualized and violent direction the industry was moving towards.

“I understood the destructive power of imagery and lyrics. I decided I didn’t want to do it anymore. I didn’t like how they were trying to push me and promote me,” says Shah. “They were grooming me to be Nicki Minaj way before Nicki Minaj and I wasn’t comfortable with that.”

Shah completely stopped recording music and focused on her family, husband (R&B artist Genuwine at the time) and raising her three daughters. Now a mother of four, Shah, who recently married Professor Griff of Public Enemy has returned to recording music. She also lectures and operates a holistic website.

In 1999 Tech N9ne also had to adjust to new fame and success. He landed on the Sway and King Tech posse song “The Anthem.” Tech had the second verse after the Wu-Tang Clan’s The RZA and was followed by Eminem, Xzibit, Pharoahe Monch, Kool G Rap, Chino XL, KRS-One. His appearance on the song proved that Tech belonged on the big stage and that Kansas City deserved attention from the rap world.

Tech has gone on to work with A-list rappers including Kendrick Lamar and Lil’ Wayne. He has appeared on several movie soundtracks and one of the biggest Hollywood stars in the world is a huge fan, so much so that not only did Dewayne “The Rock” Johnson feature his music on his HBO show Ballers but reached out personally to jump on a track. The Rock dropped a verse on Tech’s 2021 song “Face Off” off of his “Asin9ne” album.

The Rock’s feature was a big moment. Perhaps not as big as when Tech teamed up with his neighborhood brethren the 57th Street Rogue Dog Villians on the 1999 song “Lets Get Fucked Up.” The song still holds the record for being the most requested song on Hot 103 Jamz’s countdown juggernaut show “The Hot 8 at 8” and remains in rotation on most local DJ’s playlist today.

“I’m an elite emcee,” says Tech. “Everyone thinks they can rap but you have to produce something that can compete.”

“The Anthem” featuring Tech N9ne (1999) — Tech N9ne’s big break. He appears on this classic posse track along with Eminem, KRS-One, RZA, Xzibit and others.

So Fresh, So Dope

If there is a person who made it all look easy it’s Gary Edwin.

Growing up in the shadows of Southeast High School on 63rd street. Edwin began as a breakdancer. He went by the name Too Fresh and performed at parks, malls and talent shows. Tech N9ne may be the unofficial face of hip-hop in Kansas City, but DJ Fresh is perhaps the most revered.

Fresh began by creating ‘pause mixes’ on cassette tapes in 1979. Pause mixes were created by lifting songs off of the radio using a boombox as a recording device. In 1984 Fresh began DJing as Rock Master G., but his old dance stuck and eventually he became DJ Fresh. Fresh learned how to DJ by observing early DJs like Lamar “L.S. Flash” Story, one of the first DJs to scratch, cut and mix at parties. Edwin caught L.S. Flash who was DJing at a party at Lincoln High School and observed and memorized his techniques.

“I’m primarily self-taught,” says Fresh. “You just gotta watch in person and look and learn then go out and duplicate it.”

Producing mixtapes on cassettes eventually evolved to rocking house parties and becoming Kansas City’s most prolific turntablist. A skilled technician on the turntables Edwin also established himself as the go-to party DJ. But it’s Edwins entrepreneurial ambition that set him apart. DJing is the only job Fresh has ever had, capitalizing on his skill and popularity but also producing hundreds of mix tapes made him a legend and household name in Black Kansas City.

“An entire generation of people in Kansas City grew up listening to Fresh’s mixtapes,” says Goode. “It was the main way people heard hip-hop in the city for a long time.”

Edwin initially sold his mixtapes out of his van. Later they would populate the shelves at small music stores and convenience stores all over the city. You don’t receive RIAA certified gold and platinum plaques for street sales but if you did Edwin wouldn’t have any wall space left in his home or office.

The Fresh mixtapes which evolved to CDs in 1996 introduced new national and local music to its listeners. “The Fresh mixtapes was the first internet,” says Cochran. “He was our Spotify. You would hear shit that you couldn’t hear no place else.”

Fresh began independently distributing his mixtapes regionally. He survived pressure from record labels who didn’t mind supplying him with new music but would often confiscate his mixtapes claiming copyright infringement.

Edwin was also a gifted producer. His magna opus was a compilation he produced in 1998 that featured all Kansas City rap artists. “50 MC’s” was a groundbreaking project that not only unified the Kansas City hip-hop community it also helped to put it on the map.

Fresh’s soft-spoken and non-braggadocio demeanor is his greatest flex. He literally let his work speak for him as his mixtapes introduced the national hip-hop scene to what Kansas City rap was all about.

Fresh’s daughter is now continuing the family business. Tyara “DJ Tee LeChe” Edwin is now DJing. Fresh was also instrumental in jump-starting his younger brother’s rap career, more financially than creatively. Walter Edwin aka The Popper established himself as a credible lyricist in the early ‘90s after dabbling as a DJ.

The Popper began rapping in his early teens as a member of several local groups. It was the formation of The Veteran Click in 1996 that established The Popper as a credible force on the local hip-hop scene. The group consisted of his brother DJ Fresh, Eric “E-Skool” Calbert, Steven “S,G,” Garcia and his nephew Devon “The Secret Weapon” Edwin.

“The market was flooded with gangsta music,” says The Popper. “We were doing straight-up hip-hop.”

Versatility was The Popper’s calling-card. His fun and playful personality was in direct contrast to his deadly serious rhymes but often recorded lighthearted songs that connected with listeners.

“Prospect” The Popper (2018) — The song that created the celebration of Kansas City’s Hip-Hop community’s most revered street.

Prospect’s Prospects

Locally the sound of hip-hop is now everywhere all of the time. It’s the soundtrack at One Light pool parties, at fashion events like the 18th Street Fashion show, charitable events like Big Slick and at Arrowhead Stadium where Tech N9ne performed in front of 80,000 fanatics at the 2023 AFC Championship game. The culture has evolved in the fountain city.

The Popper is a prime example of the evolution of hip-hop in Kansas City. He now sells more hip-hop inspired clothing than music. “Back in 2015 I wrote a song called ‘I’m KC.’ Then I started selling t-shirts with ‘I’m KC’ on them,” says The Popper. “My legacy was tied to that shirt.”

Popper sold more than 10,000 shirts by hand in a couple of years. In 2018 he opened the first of his two I’m KC stores in the 18th and Vine Historic Jazz District selling t-shirts, jackets, basketball jerseys, baseball caps, socks, t-shirt dresses and of course his music. He opened a second store in 2021 at the Ward Parkway Shopping Mall.

His top seller now is anything with the “Prospect ” street sign logo on it—reclaiming the infamous east side street known for nefarious activities the way rappers have reclaimed the “N” word.

For most young Blacks who reside on the east side the “Prospect” brand is to them what the Charlie Hustle “KC Heart” is to newly minted urbanites. In the hood the “Prospect” graphic has become the unofficial stamp of street cred validity.

Many other rap artists in Kansas City have begun to transition into other facets of the entertainment industry. Rappers Isiah King and Victor Wilson Jr. have become filmmakers that each own clothing brands. King has produced two movies “Drout 1” and “Drout 2” and currently working on a third “Drout 3.” Wilson recently premiered a TV series he is producing “Return of the Shihan.” Currently he is shopping it for a deal.

Kemet Coleman, frontman of The Phantastics and the guy known from the 2015 Streetcar video, tapped into his entrepreneurial calling. In May he visited the White House for a symposium held by Vice President Kamala Harris for Black entrepreneurs. Coleman represented his company Vine Street Brewery where he is the company’s director of marketing and experiences. Vine Street Brewery is the first Black-owned brewery in the state of Missouri. Coleman plans to make the brewery a safe space for hip-hop. His plan is to play hip-hop music, host music release parties and incorporate live performances at the brewery when the brewery opens this summer.

Nationally the sound of hip-hop is being infiltrated by more and more by producers from Kansas City who are drastically changing the sound of the genre.

Producers like Justus West, who has produced for Snoop Dogg, Future, and Mac Miller; Denzel “Conductor” Williams who produces for Griselda, Benny the Butcher, and Westside Gunn; and Dominique Sanders, a UMKC Conservatory grad who has worked with Kendrick Lamar and Tech N9ne are not only putting Kansas City on the hip-hop map but changing the sound of hip-hop as a whole. None has done this as well as Anthony J. White known as J. White Did It. He produced Cardi B.’s monster smash “Bodak Yellow” and Megan the Stallion’s “Savage” featuring Beyoncé. His 21 Savage song “A Lot” won the Grammy for Best Rap Song in 2020.

As the music continues to evolve, a new generation of rappers have begun to blaze their own path. Artists like Sleazy World Go are ensuring that Kansas City’s hip-hop scene pushes closer to national relevancy. Sleazy World Go who was discovered on Tik Tok now represents the future of Kansas City but how people are now discovering and listening to hip-hop in general.

“Young Sleazy World Go is the first artist from Kansas City to make it big out of the gate,” says Cochran. “He went platinum with his debut. Nobody has ever done that from here. Now he’s touring the world performing at major festivals.”

The first major museum dedicated to rap is set to open soon. And no, there will not be a section dedicated solely to Kansas City. But as the culture celebrates its next 50 years, look for Kansas City to be a major contributor.

The Official Shawn Edwards

Top 50 KC Hip-Hop Tracks Ranking

- 57th Street Rogue Dog Villains “Let’s Get Fucked Up”

- Tech N9ne “Planet Rock”

- Ron Ron “Hey Honey”

- Sole “4, 5, 6”

- The Popper featuring Tech N9ne, Fat Tone and Boy Big “I Do” Remix

- Xta-C “Mr. So Heavy”

- Tech N9ne “Hood Go Crazy”

- SleazyWorldGo “Sleazy Flow”

- Basement Khemists “Correct Technique”

- Rich the Factor “Quit Calling”

- Tech N9ne “Einstein”

- Gee Watts featuring Kendrick Lamar “Watts R.I.OT.

- 57th Street Rogue Dog Villains “It’s on Now”

- Tech N9ne featuring Bakarii “Mitchell Bade”

- 2Gunn Kevi “Vent”

- Irv Da Phenom “Still”

- Tech N9ne featuring Kendrick Lamar “Fragile”

- Cash Image “In My Chevy”

- Fat Tone “Stacka Dolla (OG)”

- The Popper “Prospect”

- Sounds Good “Pacin”

- Vell Bakardy “Drink With Me”

- Don Juan “That’s Don Juan” Street Mix

- DJ Kut Fast “Butt Of The Kut”

- Dogstar D “Max and Chill”-

- Gametight Mike featuring Infinity and STK “You A Trikc”

- Tone Capone “Riding Dirty”

- Dellio “Nah Foreal”

- Made Mont “Elevated”

- YGKC “Training Wheels”

- Rich the Factor “Colossal”

- Heet Mob “KC (It Goes Down)”

- Rich the Factor “Wendy Williams”

- Dwalk “Freak Block Tales”

- Kstylis “Booty Me Down”

- KD “Jockin My Dip”

- Tech N9ne featuring Big Krizz Kaliko “I’m a Playa” Remix

- Kut Calhoun “Walk with a Limp”

- Snug Brim, Tech N9ne, and Rich The Factor “Mr. Steep Pockets”

- Hobo Tone featuring OG Riff “Missouri”

- Rich the Factor “How you Doing”

- DJ Fresh “Midwest Connect”

- Tech N9ne “O.G.”

- Kutt Calhoun featuring BG Bulletwound “All by my Lonely”

- Tech N9ne “Caribou Lou”

- Krizz Kaliko featuring Bizzy “Girls Like That”

- Tech N9ne featuring Lejo “Now It’s Own”

- J.T. Money featuring Sole “Who Dat”

- Tech N9ne “Don’t Nobody Want None”

- Don Juan featuring Rock Money and Shawn Edwards “Showtime”